In so many ways, West Virginia has been defined by coal. For more than a century, the state’s economy has been built around it, its politics dominated by it, its identity entwined with it. Even the mountains have been moved for coal.

However, this importance begs a simple question: Where does West Virginia’s coal go? Where do coal companies send it after miners dig it from the ground? What use has the world had for it so important that it defines an entire state?

To answer this question is to tell a global history. From its beginnings, West Virginia coal has been sent around the planet. It has powered fleets of ships, provided light and warmth to millions, and helped fuel our modern industrial world. At the same time, to answer this question is to understand West Virginia’s place in that world; to see the progress purchased with the state’s sacrifice to the global economy.

Once it has been mined and cleaned, West Virginia coal’s journey most often begins in a railcar. This is fitting, considering it was railroads that first made West Virginia coal possible. From early on in their colonization of Appalachia, European settlers knew about West Virginia’s coal. Thomas Jefferson even mentioned it in his Notes on the State of Virginia. However, without a way to move the coal to markets, that knowledge didn’t mean much.

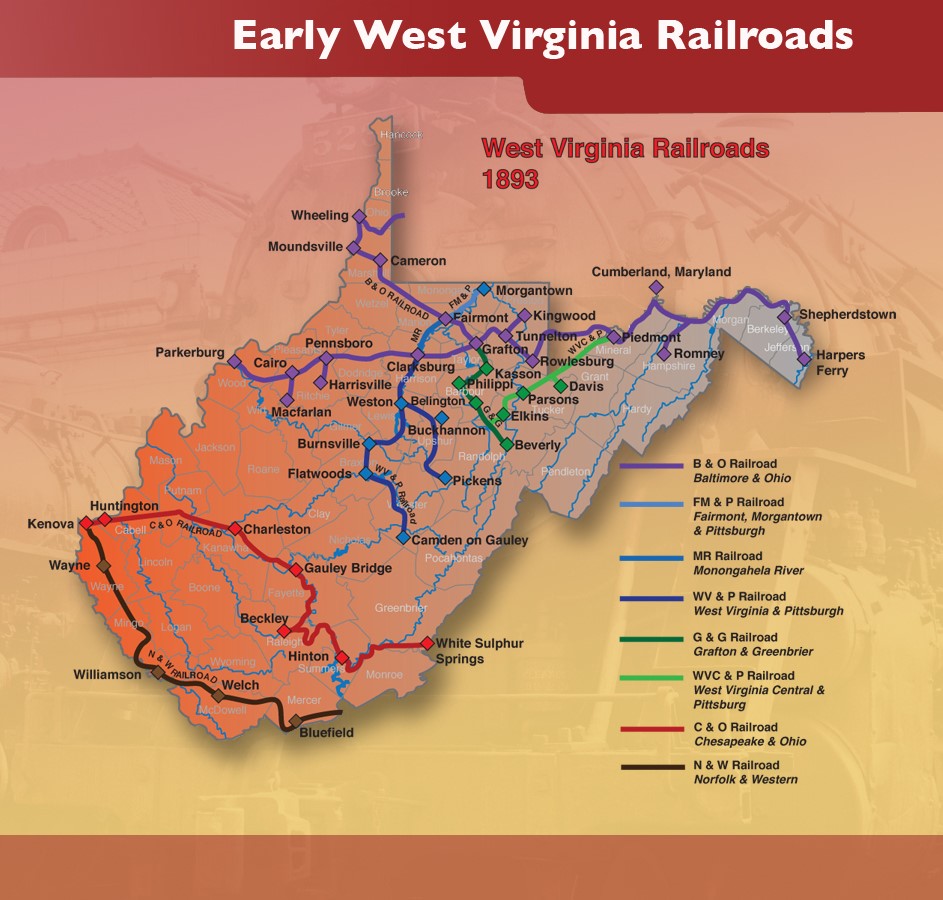

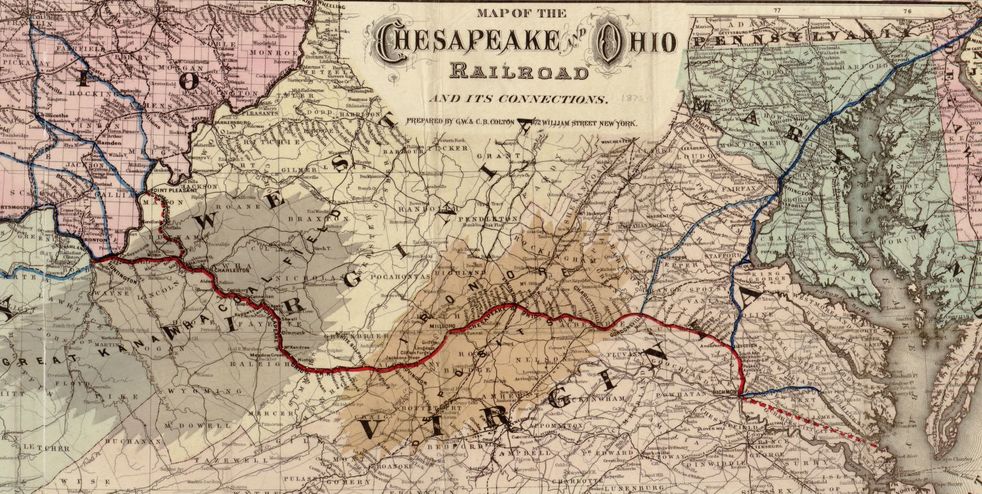

This changed when the railroads came. The Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) arrived in the 1850s, linking West Virginia’s northern coalfields around Fairmont with Baltimore. Then came the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) in 1873, linking the southern coalfields around Charleston to Hampton Roads, Virginia. Finally, in 1883, the Norfolk and Western (N&W) reached the “billion dollar” Pocahontas coalfield near Bluefield, also linking it to Hampton Roads.

With rail connections, West Virginia coal meaningfully had a ‘place to go’ for the first time, a fact reflected in massive increases in production. In the two decades after the N&W’s 1883 arrival in the Pocahontas field, annual coal production jumped from 2.3 million tons to over 29 million.

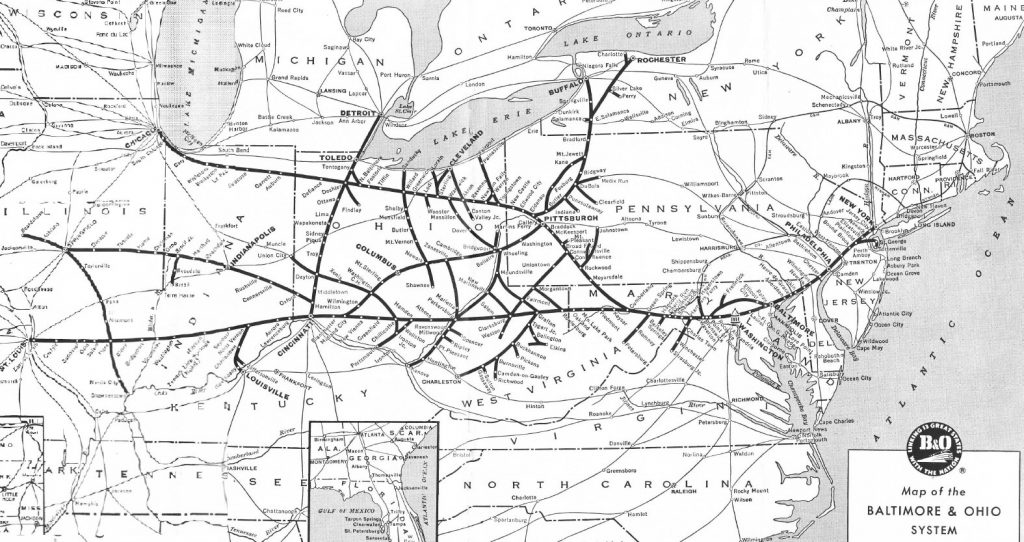

Just as important, though, was how railroads structured coal’s movement out of the mountains. Divisions between railroads meant coal went where nearby rails would take it, with the B&O carrying coal from the northern fields to places like Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Baltimore, while the C&O and N&W carried southern coal to destinations like Huntington and Hampton Roads.

Mergers have since blurred these lines, creating a “spaghetti bowl” of rails that can take coal in any direction. However, to understand West Virginia coal’s global reach, one must follow it east along the C&O railroad to Hampton Roads, where West Virginia coal first made its name on the world stage.

Best known for the battle between the Monitor and Merrimack, Hampton Roads is one of the world’s largest natural harbors. It is so large the Port of Hampton Roads comprises several cities, including Newport News and Norfolk. Together, these cities make up one of the world’s biggest coal ports, a status backed by the billions of tons of West Virginia coal shipped through them over the past 150 years.

It was here that West Virginia coal first became known to the world as premium naval fuel. Not all coal is fit to fuel ships. While anthracite doesn’t burn evenly, other coals give off too much smoke and not enough heat. However, in the late 1800s, the semi-bituminous coal from West Virginia’s Pocahontas field was found to be perfect for use in ships thanks to its even burn, considerable heat content, and relatively little smoke.

Between these properties and the seemingly limitless supply coming from West Virginia, the world was soon hooked on “Pocahontas coal”. In 1889, the US Navy ordered all new ships to undergo testing using it, and it was soon the standard against which all other coals were rated. By the early 1900s, the US Navy would only fuel its ships with West Virginia’s ‘navy grade’ coal, requiring shipment to naval stations as far afield as the Caribbean, the Philippines, and Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

Perhaps the best example of Pocahontas coal’s reach was the Great White Fleet. Assembled by President Roosevelt in 1907 to display the US’s growing naval power, the Great White Fleet was a 14-month, 43,000 mile voyage of 16 American battleships that circumnavigated the globe. Stops included Rio de Janeiro, Tokyo, and the Suez Canal. However, underlining the importance of West Virginia coal in such a display, the unprecedented voyage both began and ended at Hampton Roads, where the fleet’s bunkers were filled with Pocahontas coal for the journey.

The US Navy’s shift to oil after World War I was the beginning of the end for Pocahontas coal’s use as a naval fuel. However, the 100 million+ tons of West Virginia coal being mined every year by the mid-1920s still found many homes—literally. Beginning in the late 1800s, bituminous coal, the type mined in West Virginia, became the most widely used heating fuel in the US, with 41 percent of American households using it by 1940.

Although forced to compete with coal from other areas, West Virginia coal quickly made inroads into much of eastern North America. From the late 1800s onward, a major market was New England, with coal shipped to Hampton Roads, then loaded onto coastal barges bound for ports like Boston and Providence. In 1925, about 15 million tons of coal—12 percent of West Virginia’s annual production—was shipped from Hampton Roads along the Atlantic Coast like this, with the majority going to New England.

Elsewhere, a mix of barge and rail traffic carried West Virginia coal west. By 1940, ports like Huntington on the Ohio River and its tributaries were shipping over 8 million tons of southern West Virginia coal a year downriver to cities like Cincinnati and Louisville, and coal from the northern fields made up some of the 24 million tons shipped up the Monongahela River to Pittsburgh. Meanwhile, railroads like the B&O carried coal to Great Lakes ports in northern Ohio like Cleveland, Ashtabula, and Toledo, from which more than 43 million tons of bituminous coal was shipped to places like Chicago, Milwaukee, and Canada in 1940.

Displaced by cheaper and cleaner oil and gas, West Virginia coal’s use in heating fell in the decades following World War II. However, during the same period its use in coal-fired power plants skyrocketed. By 1970, 47 percent of coal mined in Appalachia was used in electrical generation, rising to 62 percent in 1984. In 2002, about 67 percent of the coal mined in West Virginia—101 million tons—was used to produce electricity.

Historically, most of this electrical coal has been shipped to more populous states nearby, with 47 million tons to Ohio, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania in 2002. However, much has stayed closer to home for use in one of West Virginia’s many coal-fired power plants, helping make the state one of the US’s top electricity exporters. Despite being home to half a percent of the US population, West Virginia produced 2.3 percent of all US electricity in 2005.

Since peaking in the mid-2000s, West Virginia coal’s place in electrical generation has been displaced by other energy sources, with many coal-fired power plants retired or converted. Of course, concerns over climate change and the rise of renewable energy have played a role in this switch. However, as with home heating in the mid-20th century, a major factor in coal’s displacement has been the availability of cheaper and cleaner natural gas from America’s fracking boom.

Whatever its cause, this shift in energy generation has contributed to a massive drop in West Virginia coal production. From a near-record high of 169 million tons in 1990, West Virginia produced just 93 million tons in 2018, with less than half of that being used to produce electricity.

Nevertheless, despite this decline, West Virginia coal still has one major use that sees it shipped around the world—metallurgy.

From the 19th century until today, metallurgy has been an important use for West Virginia coal. For many of the same reasons it was valued as a ship fuel, West Virginia coal is also well-suited for use as coke in steelmaking, and coal from the state helped fuel the steel industry around nearby Pittsburgh and Youngstown for over a century.

Of course, deindustrialization in the late 20th century changed things, with West Virginia coal destined to US steelmakers dropping by at least 50 percent between 1970 and 2019. However, while the US steel industry was experiencing this downturn, the West Virginia coal industry witnessed a new development—the rise of international markets.

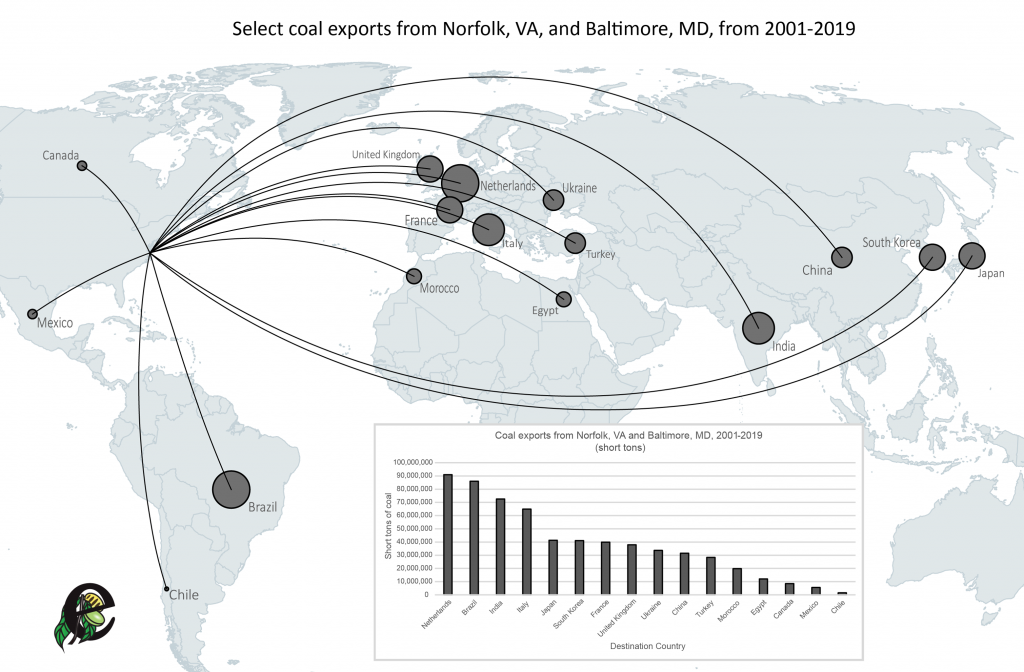

Due to its rare status as a high-quality metallurgical coal, West Virginia coal has always found markets overseas. Millions of tons made their way to Europe as part of the United States’ Marshall Plan following World War II, and it has since developed decades-long customers among steelmakers in countries like Brazil, Italy, and Japan. However, foreign exports were historically a minor destination for West Virginia coal, accounting for just 13 percent of production—22 million tons—in 2001.

This changed in the early 2010s, when industrializing countries in Asia like China, South Korea, and India started importing West Virginia coal in dramatically increased quantities. Peaking at 47 million tons in 2012, this boom in exports, combined with the wider decline in coal mining, means overseas markets now receive more than a third of West Virginia coal production, with 41 percent of the state’s coal bound for foreign countries in 2018.

Whether overseas markets will provide a permanent refuge for West Virginia coal remains to be seen, with some analysts interpreting the 2010s export boom as an anomaly in global trends. Regardless of what ends up being the case, foreign exports’ recent prominence underlines West Virginia coal’s long history as a global commodity.

This history should in many ways be a source of pride for West Virginians. Far from being isolated and backward, coal’s worldwide journey illustrates how West Virginia has been an important node in modern society for over a century. The world as we know it today would not exist without the sacrifices of West Virginia miners and their communities.

However, in marveling at this achievement, West Virginians must not forget the other side of coal’s story. At the same time West Virginia coal provided warmth to millions, West Virginians were fighting for their rights at Blair Mountain. At the same time the West Virginia coal industry was profiting off foreign exports, West Virginia miners were dying at Upper Big Branch. And at the same time West Virginians are struggling for a future where they don’t have to wonder where the coal goes, those invested in the state’s sacrifice insist on living in the past.

In understanding these two, interconnected sides of coal’s global history, West Virginians can be better equipped to navigate where they would like their state to go.

Some recommended resources on West Virginia coal’s global history:

- Coal and Empire: The Birth of Energy Security in Industrial America by Peter Shulman

- The Story of Castner, Curran, and Bullitt, Inc., 1867-1967 by Castner, Curran, and Bullitt

- Coal Data Browser by US Energy Information Agency

- Annual Coal Distribution Reports, 2001-2019 by US Energy Information Agency

- Chief’s Annual Reports, 1850-2018 by US Army Corps of Engineers

Special thanks to Dr. Sean Patrick Adams for providing invaluable guidance on the history of coal in the research of this piece.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nicholas Brumfield is a native of Parkersburg, WV currently working in Washington, DC. For more hot takes on Appalachia and Ohio politics, follow him on Twitter: @NickJBrumfield