Cultural festivals are a long-standing American tradition, a way for immigrants and their chosen cities to celebrate their roots. On September 21, as they have done for 42 years, thousands of people flocked to downtown Cincinnati to enjoy the sights, sounds, and tastes of Oktoberfest Zinzinnati, the city’s annual celebration of all things German. Guests enjoyed classic German food, beer, and music, as well as more modern traditions like a weiner dog race, a communal chicken dance, and polka rock fusion bands.

“Our team is always looking to innovate,” said Rich Walburg, director of communications for the Cincinnati USA Regional Chamber of Commerce, when asked about the fest’s unique lineup. “That’s what put us on top.”

All told, an estimated 600,000 people celebrated what one German newspaper dubbed “America’s Oktoberfest,” making Cincinnati’s event the largest of nearly 700 Oktoberfests scheduled in the United States. Only Munich’s Oktoberfest draws bigger crowds. These Oktoberfests demonstrate America’s clear fondness for German culture—or, at the very least, German beer.

Yet, in our rush for good lagers, it is easy to miss the deep history of German America behind Oktoberfest. Having in some ways become the mainstream, many German-Americans seem to have forgotten the time when they were America’s biggest immigrant group.

Coming to Appalachia

While it may be difficult to imagine today, Germans were a distinct immigrant community for much of America’s modern history. From 1820 to 1910, over 6 million Germans immigrated to the United States, settling a vast swath of the country from Pennsylvania to Oregon. Peaking at 2.8 million people in 1890, the foreign-born German population constituted almost 4.5 percent of the population. By comparison, the foreign-born Mexican population in the United States in 2013 was about 3.6 percent.

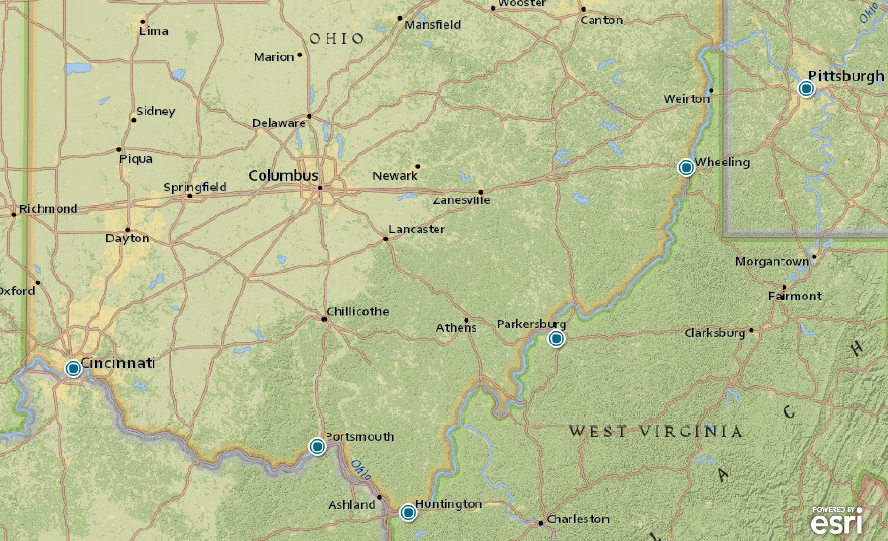

In Appalachia, German immigrants flooded into the Ohio River Valley. Germans were the largest foreign-born population in Ohio and Kentucky in every census from 1850 until 1920, and in 1900, they formed the largest foreign-born contingent in every state in Appalachia except Virginia and Alabama. Major cities like Pittsburgh and Cincinnati overflowed with German immigrants—in 1890, 57 percent of Cincinnati’s 300,000 people were either born in Germany or had German parents. Germans also poured into the small towns and countryside of northern Appalachia, settling or expanding communities like Lancaster, Portsmouth, New Philadelphia, and Pomeroy in Ohio; and Wheeling, Parkersburg, and Huntington in West Virginia.

Although settling in what would become Middle America, German immigrants often weren’t keen to fully assimilate. Many German parents sent their children to German bilingual schools, congregated in German-language churches and synagogues (the last such church in Pittsburgh closed in 1974), and formed organizations dedicated to maintaining a distinct German-American identity. Histories from towns throughout the Ohio Valley note that German culture was so dominant that people had to know both English and German to do business. German identity could also be a source of tension and, at times, Germans were the target of ethnic riots.

All this isn’t to suggest that German-Americans were some uniquely persecuted minority. As the whitest ethnic group after the English in America’s elaborate racial hierarchy, Germans were often esteemed as the “model immigrant” above their Irish and Italian compatriots, and they could be just as racist toward African-Americans as the rest of white America. As some of the earliest settlers to Appalachia and the Midwest, they also played key roles in dispossessing those regions’ indigenous peoples. However, for a significant portion of their time in America, German-Americans constituted a distinct ethnic community. This begs the question: Where did that community go?

Becoming “Old Stock”

There are a lot of reasons why the German-American community ceased to be a force in American society. By the turn of the 20th century, the forces of American nationalism, racism, and contempt for “new immigrants” had already prompted many German-Americans to define themselves as white instead of German. However, the most direct cause for the decline of German America was the US government-led suppression of all things German during World War I.

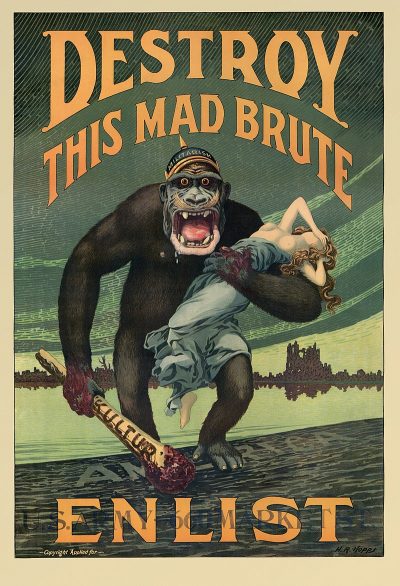

The American home front was a pretty dangerous place during World War I. The government actively promoted censorship and hysteria, and imprisoned anti-war activists. Anti-German sentiment was a central component of the campaign to defeat the Kaiser. In war propaganda, Germans were portrayed as an inherently violent people deserving of annihilation, and more than 250,000 German-Americans were forced to register with the state to be monitored. The German language, commonly used in communities across the country, was banned for fear that German language instruction was “propaganda to overthrow English.” German shops were boycotted and German organizations were forced to close. At their most extreme, those sentiments led to violence, with a mob hanging an immigrant coal miner in Collinsville, Illinois on April 5, 1918.

In the Ohio Valley, this sentiment was alive and well. The Clarksburg (WV) Daily Telegram applauded an “America for Americans campaign” and the Fairmont (WV) Times openly doubted the loyalty of all 500,000 un-naturalized Germans in the United States. In Huntington, WV, factory workers forced un-naturalized German workers to fly the American flag by turning a firehose on them. Even Columbus native Eddie Rickenbacker, America’s most famous WWI fighter ace and the son of German immigrants, changed his last name from Rickenbacher to avoid suspicion. In Cincinnati, the city’s German landmarks were renamed, German newspapers were forcefully closed, and the Austrian-born conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra was imprisoned and deported.

By 1920, the German-American public sphere that was so vibrant a generation before was no more. According to German-American identity scholar Russell Kazal, its suppression played a key role in the fall of “an earlier, more pluralist America” in favor of “a more exclusive and conformist American nationalism.”

Despite the fact that more Americans claim German ancestry than any other, German-American cultural identity has never truly recovered.

A Call for Hidden Histories

The rise and fall of German culture in Appalachia offers a major lesson to those who study the region’s history: things are not always what they seem.

Although much smaller than Oktoberfest Cincinnati, on September 30th, the city of Boardman, Ohio, a town of 35,000 just south of Youngstown, also hosted its 42nd Oktoberfest. A much less self-conscious affair, Boardman’s Oktoberfest consisted of a small gathering of craft tents and food trucks, a fundraiser for the local Rotary Club, and a parade starring the local school band. It was in many ways the epitome of what people love about small-town America. It is also a legacy of German Appalachia, the result of a dynamic history of immigration and change hidden in plain sight. In thinking about Appalachia, we must seek out these “hidden histories” to provide a more complete, more inclusive picture of what the region means to its people.

Subscribe to The Packet, our newsletter launching later this month, to stay up-to-date with new Expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Book recommendations:

Becoming Old Stock: The Paradox of German-American Identity

Bonds of Loyalty: German-Americans and World War I

The Americanization of West Virginia

German Marietta and Washington County

If you have a story you think needs told, email Nicholas at nicholas@expatalachians.com.

Nicholas Brumfield is a native of Parkersburg, WV currently working in Arlington, VA. For more hot takes on Appalachia and Ohio politics, follow him on Twitter: @NickJBrumfield.