A crowd of onlookers in Charleston, West Virginia gazed upward as the first series of black dots appeared on the horizon on September 2, 1921. As the dots crept closer, they became biplanes roaring toward the makeshift air strip in Kanawha City, then a small community on the eastern outskirts of Charleston.

To the cheers of the crowd, the first De Havilland-4B (Dh-4B) fighter planes of the U.S. Army Air Service’s 88th Air Squadron touched down in West Virginia, bringing modern military power to that summer’s violence in southern West Virginia.

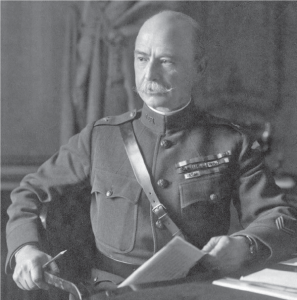

A week earlier, Assistant Chief of the United States Army Air Service General William “Billy” Mitchell arrived in Kanawha City on August 26. Mitchell had led the Army Air Service at the end of World War I, and three years following the Armistice was still eager to prove the use of air power to the high command in Washington, D.C. While Mitchell and his airmen had demonstrated the use of aircraft in naval warfare a few weeks earlier when they sank the captured German battleship Ostfriesland off the coast of Virginia, he was now focused on proving the usefulness of air power in disbursing civil disturbances, particularly in remote areas such as central Appalachia.

To the gaggle of reporters who met Mitchell upon his arrival, the general was quite clear about his intentions. “We wouldn’t try to kill these people at first,” Mitchell said. “We’d drop tear gas all over the place. If they refuse to disburse, then we’d open up with artillery and everything.”

“These people” Mitchell referred to were the miners of the Kanawha and New

River coalfields who had begun a march south to “liberate” the striking miners in Mingo County, which had been placed under martial law.

By 1921 much of the state’s coal-producing regions had been unionized by the United Mine Workers of America; however, the mine operators in Mingo and a few surrounding counties resisted such efforts to the point of violence. The “Matewan Massacre” happened the previous summer, leading to the deaths of seven Baldwin Felts agents under contract from the coal operators to carry out evictions on striking miners.

The shootout in Matewan and corresponding fallout escalated the tensions in Mingo County and another battle—this time with state police to reinforce the Baldwin Felts agents—occurred the following year. Unable to control the situation, West Virginia’s newly inaugurated governor, Ephraim Morgan, re-established the National Guard and imposed martial law in Mingo County, ironically making his proclamation on the one-year anniversary of the “Matewan Massacre.”

The presence of state police and national guardsmen only escalated the situation, as the state’s law enforcement acted more as agents of the mine operators than an independent force of peace. By late August, after multiple skirmishes between miners and the law, President Warren G. Harding finally succumbed to the pleas of Governor Morgan and sent Brigadier General Harry H. Bandholdtz to Charleston to assess the situation.

Arriving in the pre-dawn hours of Friday, August 26—just hours before Mitchell—Bandholtz immediately met with state and union leadership separately to de-escalate the situation. While Mitchell was anxious to demonstrate the deadly force he could deploy from above, Bandholtz urged restraint, hoping that the miners would stand down on their own without the use of federal troops. That seemed to be the likely conclusion by the end of the weekend, and both generals returned to Washington with reports of peaceful resolution in tow.

These reports, however, were premature.

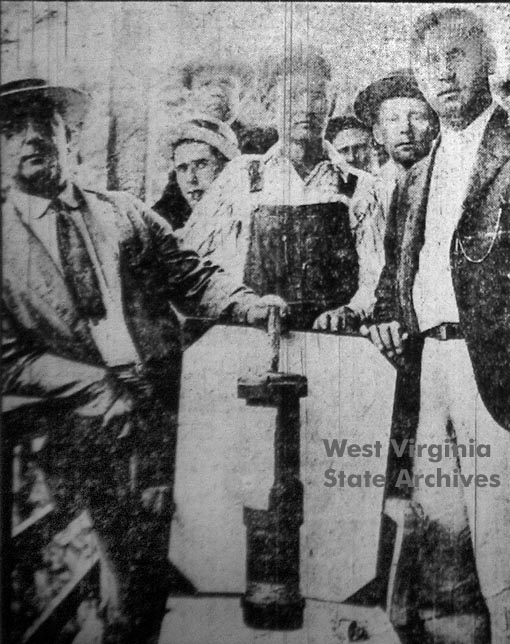

By midday on Monday, August 29 a skirmish between miners and state police had reignited the fuse and the miners’ army had turned back toward Mingo County. Directly in their path was Logan County, another holdout of non-unionized mines. The sheriff of Logan County, Don Chafin, was rabidly anti-union and had raised a small force to supplement existing state and local law enforcement in the county, declaring that “No armed mob will cross Logan County.” Chafin’s 3,000 men had dug in along Blair Mountain. As the first columns of the “Red Neck Army” of miners approached the ridge, Chafin’s men began firing small arms and machine guns from entrenched positions. The Battle of Blair Mountain had begun.

Bandholtz returned to West Virginia on Thursday, September 1 as the battle was still underway. While still hoping to avoid a pitched battle involving federal troops, he wasted no time in ordering three regiments of infantry to converge on West Virginia’s southern coalfields to pacify the area. Meanwhile, Mitchell, not wanting to miss a second opportunity, ordered the 88th Squadron of the Army Air Service to West Virginia.

The art of flying was still relatively primitive in 1921, the open-air cockpits and lack of instrumentation forcing pilots to fly lower to the ground and only during daylight hours. All 17 of the 88th Squadron’s Dh-4Bs arrived in their stopover point of Roanoke, VA without issue. The second leg of their journey, however, would not be as easy.

Taking off toward Kanawha City on the morning of Friday, September 2, the size of the squadron had already been reduced by two due to mechanical issues. Of the 15 planes that set off from Roanoke, one crashed during takeoff and two were lost in fog and ended up in Tennessee. The two lost planes then crashed the next morning en route to West Virginia. Fortunately, none of the crew members were seriously injured in any of the mishaps, and 11 Dh-4Bs made it to Kanawha City.

Upon their arrival to West Virginia, the chance of aerial bombardment by the Air Service was quickly snuffed out. Fully loaded with bombs and machine guns when they left their home base of Langley, VA, the 88th Squadron’s planes were stripped of all weaponry before flying over Blair Mountain. Bandholdtz’s orders were clear. “You will under no circumstances drop any bombs or fire any machine guns or do anything to unnecessarily excite the invaders,” he wrote in a dispatch. While the 88th Squadron was used to assess the situation on Blair Mountain from above, there would be no demonstration of the Air Service’s armed abilities in West Virginia.

There were, however, a trio of private biplanes rented by Sheriff Chafin that were not under the strict orders of restraint from General Bandholtz. On September 2—the same day as the Squadron’s arrival in West Virginia—Chafin ordered his own small air force to drop gas and makeshift bombs on the miners’ positions on Blair Mountain. Though none of these aerial assaults struck their intended targets, Mitchell’s braggadocious comments to the Charleston press the week before led many to believe that the Army had conducted the bombing runs, a myth that remains today.

Rather, the only casualties directly related to the airplanes in the West Virginia Mine Wars were the deaths of three airmen on Friday, September 2. In addition to the 88th Squadron’s 17 Dh-4B fighter planes, Mitchell had also dispatched four Martin MB-2 bombers from Maryland, which arrived in Kanawha City on September 1. Like the fighter squadron, the bomber unit was incomplete, with one bomber forced to land in Fairmont, West Virginia after being blown off course.

Once Bandholtz made it clear that the Army Air Service would be used strictly for reconnaissance, Mitchell ordered the MB-2s back to Maryland the following day. Flying through a storm south of Charleston, Lieutenant Harry L. Speck lost control of his plane, which fell in a nose-dive into a densely wooded hill. While the other two aircraft were able to make safe emergency landings, three of the four crew in the crashed plane, including Speck, were killed. The fourth—Corporal Alexander Hazelton—was paralyzed but rescued two days later once local authorities found the crash site.

While seemingly an exciting series of escalations, the Battle of Blair Mountain and the Miners’ March on Mingo ended abruptly over the weekend of September 3-4 as federal troops from Ohio, Kentucky, and New Jersey arrived by train. The Army was seen as a neutral force not under the influence of coal operators and a formidable and unwanted opponent by the miners.

Many of the men on Blair Mountain had served in World War I, and at the very least nearly all considered themselves patriotic. Fighting corrupt state forces was one thing, but fighting the United States Army was beyond the fire in the miners’ bellies. By September 5, nearly all of their weapons had been turned in and most were on their way home.

Despite the loss of three of his planes and the fact that a full third of the force never even reached Kanawha City, General Mitchell spun the mission as a success. He later called the expedition, “an excellent example of the potentialities of air power, that can go wherever there is air.” He continued to find controversy throughout the remainder of his career, often butting heads with his superiors in Washington. Five years later, in 1926, General Mitchell resigned from the Army after being court-martialed and suspended from active duty.

The use of air power by the United States Army during the West Virginia Mine Wars still stands as the only time that American military aircraft were used during a domestic civil disturbance.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nick Musgrave first became fascinated with West Virginia’s history while growing up in Parkersburg. He continues to read, research and write on the Mountain State’s past from its birthplace in Wheeling. For more neat history and some political snark, follow him on Twitter: @NickMusgraveWV.