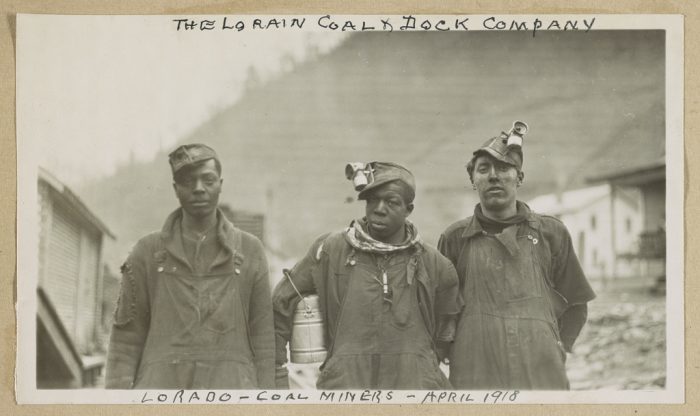

Three miners in Lorado, Logan County. Via The Library of Congress.

As the swing of a pick opened West Virginia’s Pocahontas Coalfield in 1883, the region looked much as it did two decades earlier at the state’s birth. Though the Civil War’s end and the Thirteenth Amendment’s passage secured the freedom of the area’s slave population, the number of black residents in 1880 barely budged from 1860. The majority of the southern-most Mountaineers were still white and staked out a living through subsistence farming or small-scale timber harvesting. The initial contact of steel and coal, however, would transform the region’s citizens and economy to the present day.

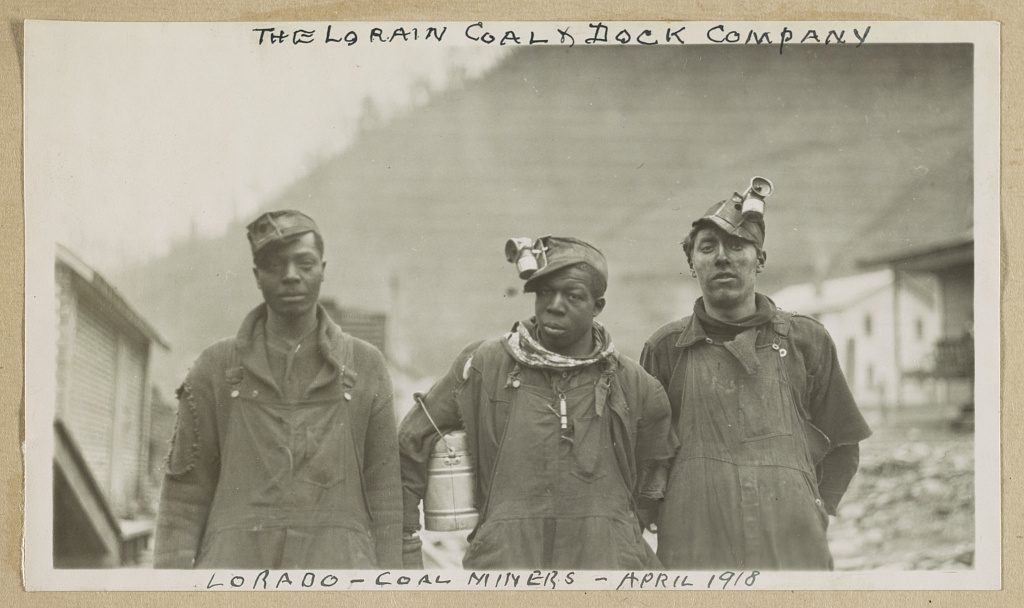

The Pocahontas Field, along with the nearby Kanawha-New River, Winding Gulf, and Williamson-Logan coalfields, would form the nexus of coal production in southern West Virginia and attract hundreds of thousands of workers from across the United States and Europe to crawl underground and fuel America’s industrial rise. Among these mountain migrants were scores of black workers and their families in search of opportunity and an escape from the Deep South during the rise of Jim Crow.

The coalfields of West Virginia, including the four southernmost fields with the highest black employment rates: Kanawha-New River, Pocahontas, Williamson-Logan and Winding Gulf. Via The Library of Congress.

The coal companies played a self-serving role in bringing cheap labor to the region, recruiting black workers from the nearest Southern states, primarily Virginia. From 1900-1930, nearly as many of West Virginia’s black residents were born in the Old Dominion as in the Mountain State.

Though all nine counties in West Virginia’s southern coal-producing region saw large increases in their black populations between 1880 and 1920, McDowell and Mercer Counties (in the Pocahontas Field) had the largest percentage of blacks both in the county and employed in the coal industry. By 1917, one in every three miners working in the Pocahontas Field were black, the majority of whom worked the hardest, worst-paying jobs of loader and laborer: digging, loading, and hauling the coal in dangerous underground conditions. In the 1921 report from the West Virginia Bureau of Negro Welfare and Statistics, only 231 of the nearly 6,500 blacks employed in the industry worked higher-paying skilled jobs and a paltry seven were foremen. Though in many ways the opportunities afforded to black workers in the coalfields were greater than work in the Deep South, inequality and discrimination still permeated the workplace.

The state was not far removed from Southern Democratic politics that kept an iron grip on statehouses below the Mason-Dixon Line through the 20th century. Though West Virginia’s statehood was undeniably the product of 1860s Republicanism, by the 1870s, control of the state’s government had shifted to the Democrats, who quickly instituted school segregation and denied blacks the right to serve on a jury. While in some parts of the state, segregation beyond education was laxly enforced, the southern coalfields endured much stricter separations of the races. Theaters and public accommodations were segregated, and blacks were not welcome at company town hotels and restaurants. However, West Virginia differed from the South in protecting and upholding universal suffrage. Civic culture thrived within the black communities of southern West Virginia, which led to the election of the first black member of the House of Delegates, Christopher Payne of Fayette County, in 1896.

While the state government was not as harsh in handing down de jure discrimination, the unparalleled control that coal companies had over the miners’ lives worsened the conditions of working-class blacks. While black workers in northern cities such as Detroit or Chicago were forced into segregated neighborhoods by racist housing policies and violence in the 1910s, miners of all race and creed in southern West Virginia were housed at the pleasure of the company, ensuring that black miners were placed in the oldest and least-maintained dwellings within coal camps.

In contrast, the organized labor movement, especially the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), offered relative equality. While labor unions in the South were plagued with internal controversy over whether to include blacks early on, the UMWA was known as one of the leading labor organizations for interracial membership. Founded in 1890 just months after the union itself, District 17 initially covered all of West Virginia before being split in 1924 and again in 1942, though the southern coalfields remained primarily part of District 17. Black miners were generally welcomed into the union and held seats on the District’s executive board, as well as leadership positions in the various locals.

A coal mining family carrying groceries in Kingston, McDowell County. Black miners were often given the smallest and least-maintained housing in the coal camps. Via WeHeartWV.com.

While the state government in Charleston was slightly more progressive than their southern neighbors in terms of codified racial discrimination, they fiercely resisted the unionization of southern West Virginia. With the full support of the governor and legislature, coal companies instituted no-tolerance policies toward union organization, evicted miners suspected of union sympathies, and violently harassed the makeshift camps of intentionally displaced families. Strikes often turned violent: Intense bloodshed resulted from multiple gunfights between striking miners and private detectives sent to deal with the so-called “troublemakers.”

This bloodshed peaked in 1921 with the organization of an armed “Miners March” into Mingo and Logan Counties in the Williamson-Logan Field, which was among the last strongholds of non-unionized coal camps. Included in the estimated 15,000 armed miners were 2,000 black miners, predominantly from the Kanawha-New River Field, which had seen its own share of intense violence during unionization. Much like the shared experience of military service in later decades, the Miners March and its climactic Battle of Blair Mountain fostered a deep sense of camaraderie and loyalty between black and white miners alike.

Agents deputized to stop the Miners March at the Battle of Blair Mountain. Across the ridge were 2,000 black miners who marched and fought alongside the striking miners of Logan and Mingo Counties. Via West Virginia State Archives.

The rise of the UMWA and inclusion of black miners may have spared the region from some of the nationwide violence during the Red Summer of 1919. It is important to note that the sole lynching in the coalfields that summer, the murder of two black miners by a white mob in Logan, occurred in the very area already fraught with violence from the unionization struggle. The county sheriff who refused to investigate the lynching was Don Chaffin, the same Logan sheriff who organized the army of deputies and private agents who faced off against the UMWA at the Battle of Blair Mountain.

While black employment in the southern coalfields remained steady up to 1930, the Great Depression brought disaster to the industry. Despite better work conditions after unionization, black miners were still the first to be laid off during declines in coal production. By the time the economy recovered, mechanization took hold in the mines and many of the jobs lost in the depression never came back, especially for workers of color. While blacks had made up at least a fifth of West Virginia’s coal miners since 1900, by 1940, that percentage had fallen below 20 percent for the first time—and fell precipitously in the subsequent decades. Today, less than 3 percent of coal miners in West Virginia are people of color.

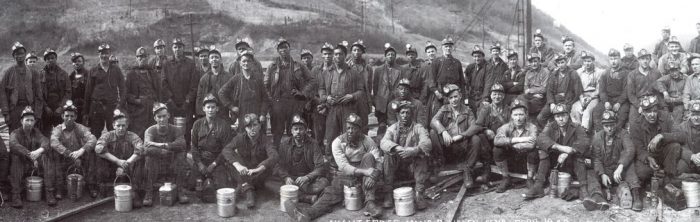

A group of coal miners in Helen, Raleigh County in 1947. Between 1880 and 1940, thousands of blacks, poor native-born whites and immigrants migrated and worked alongside one another in the southern coalfields of West Virginia. Via National Park Service.

The remnants of the southern coalfields’ black workforce remain present in the region’s culture and demography. Of the 10 West Virginia counties with the highest percentage of black residents, six are in the coalfields, though not one has a black population above 10 percent. Though contemporary West Virginia politics and its embrace of Donald Trump has led to some outside observers to focus on the state’s whiteness, the coal behind the state’s identity was once mined, loaded, and hauled by thousands of black miners who spent their lives working underground.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nick Musgrave first became fascinated with West Virginia’s history while growing up in Parkersburg. He continues to read, research and write on the Mountain State’s past from its birthplace in Wheeling. For more neat history and some political snark, follow him on Twitter: @NickMusgraveWV.