Although often seen as a rural region, Appalachia includes cities within its borders and a few beyond. Cincinnati, Detroit, and Dayton all have enclaves of Appalachians who left for jobs during the manufacturing boom in the Midwest, and cities within the region like Pittsburgh, Asheville, and Knoxville attracted rural workers, too.

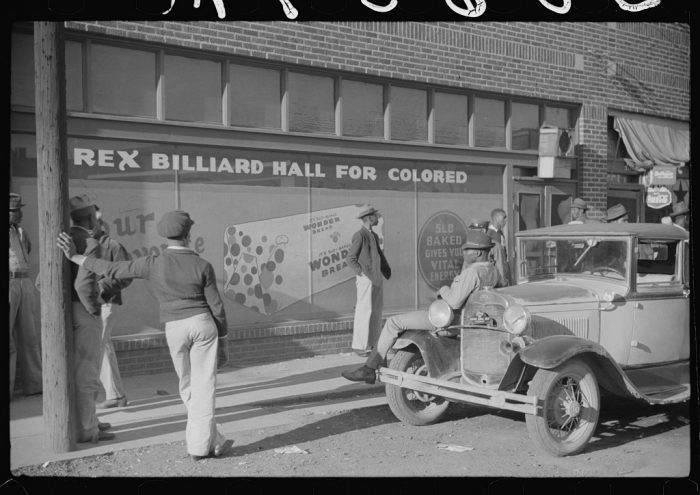

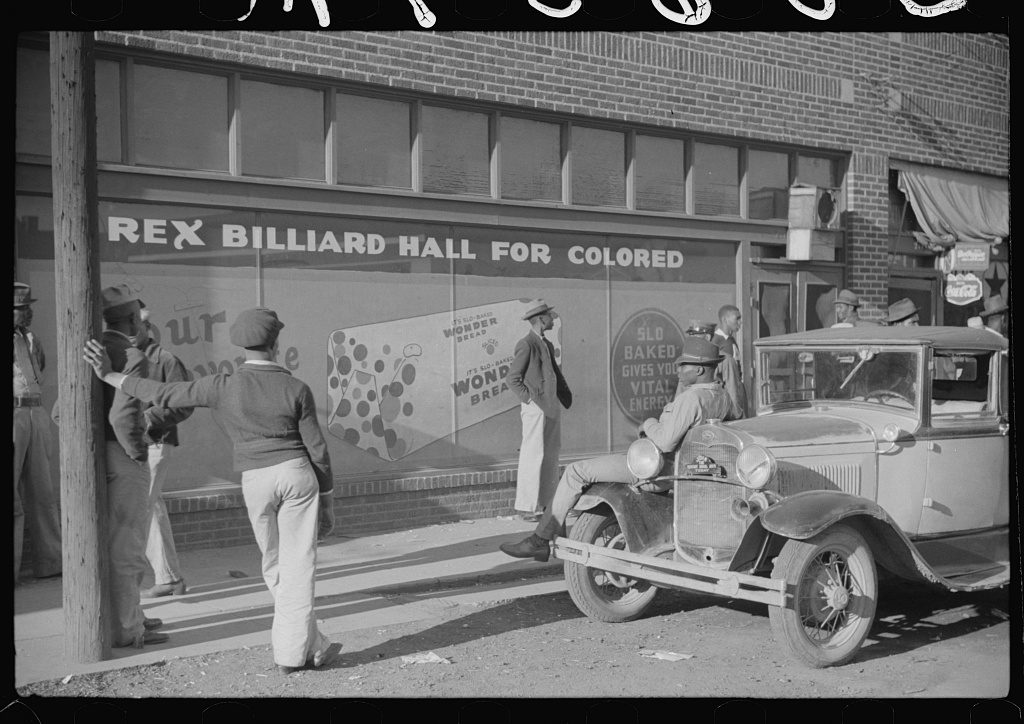

Like many places in urban America, race was a central factor in several Appalachian cities. Knoxville, for example, had a race riot and attempted lynching in 1919 during the “Red Summer,” when race riots broke out in two dozen cities, many of them instigated by white citizens for imagined black crimes or black demands for equality.

Then, during the Civil Rights Movement, Knoxville had a rare experience in desegregating lunch counters. While white supremacy was the norm in most instances, the city also had its own victories for racial equality.

Knoxville succeeded in peacefully desegregating its lunch counters—and at a brisk pace compared to other southern cities. When the first prominent sit-in occurred in Greensboro, North Carolina in February 1960, it took six months and near constant pressure for civil rights activists to win out. The sit-in movement used non-violent methods to protest the “separate but equal” standard that underpinned racial segregation throughout the United States. Knoxville activists emulated the Greensboro action, yet achieved integration in just over a month after intensive action was taken starting in June 1960.

The desire by city and business leaders, too, to preserve Knoxville’s reputation as a city without racial tension, pushed them to resolve the protests quickly and quietly.

One key reason was that the activists had political backing: Mayor John Duncan supported integration. As historian Cynthia Griggs Fleming noted,

Duncan unequivocally articulated his determination to minimize conflict and protect demonstrators from violence. One of the black leaders of the demonstrations recalled the mayor’s instructions to him: “Just call me each morning—where you’re going to be, and we’ll have protection there.”

If white segregationists harassed black activists, they would be arrested. Throughout the month-long sustained campaign of sit-ins, boycotts, and picketing, Knoxville police enforced the rule of law and didn’t arrest the activists.

Another reason why activists were so successful so quickly may have been that, though students began the desegregation effort, black professionals quickly took over. When students from historically black Knoxville College announced their intention to protest in February, community leaders persuaded them to wait and try to negotiate. After months of waiting with no progress, students tried an early week of sit-ins on May 12.

Students stopped after a week at the requests of local businesses, who implied they would reconsider segregation after a cooling-off period. When this didn’t happen after the break, the majority-black Association Council for Full Citizenship joined in the direct action, planning a prolonged campaign starting on June 9. “Many Associated Council members were quite distressed by having to take such a step [to demonstrate],” Fleming wrote. “They had always thought their city was different, but their city had let them down.”

When businesses relented and announced on July 12 that lunch counters would be integrated, not all activists were pleased. The local press followed the city government’s “request” not to cover the protests for fear of outside agitators and inflaming racial tension.

Jerry Pate, a student demonstrator, said that “things in Knoxville were too easy, and only surface change occurred.” No violence erupted, the press didn’t cover the protests, and it ended quickly; Knoxville whites were hardly aware of the sit-ins until they were almost over. For Knoxville blacks, it was a different story. “These demonstrations finally forced all black Knoxvillians, despite their reluctance, to come to terms with their subordinate status,” Fleming wrote.

This subordinate status, Fleming noted, grew from a certain sort of white paternalism. White Knoxville lived in an ignorant sort of bliss: “Most Knoxville whites,” Fleming wrote, “had never realized the existence of any dissatisfaction among the city’s blacks.” Knoxville had fewer black residents than Nashville and Memphis. While black Knoxville was only 7.5 percent of the population in 1960, black Chattanooga was 17.6 percent of the city, black Nashville was 19.2 percent, and black Memphis was 36.4 percent.

Thanks to Knoxville’s smaller black population, the legal segregation system was less rigid than further south. However, the relative “privileges” black Knoxvillians retained were still “severely circumscribed.” As a black Knoxville native told Fleming, “They always gave us enough in Knoxville to be content, but not ever get ahead.”

One outgrowth of white leaders in Knoxville not understanding black dissatisfaction could be seen in “urban renewal,” a plan to redevelop parts of the city that stretched from the 1950s into the 1970s. The would take private land using the eminent domain power to be redeveloped for private or public use as the city saw fit.

The effects of urban renewal were devastating. In Knoxville, it

destroyed three Black communities that were located in the eastern region of downtown and displaced hundreds of Black residents. Terms like “slum” and “blighted” were imposed on Black spaces. Rather than improving the standard of living in Black neighborhoods, the city, through these projects, transformed Black neighborhoods and the nerve center of Black commerce into concrete highways, apartment buildings and public facilities, including the Civic Coliseum.

When investigating the effects of urban renewal, Robert Booker, a Knoxville native who was active in the 1960 sit-ins, found that the projects “decimated the black community. They took hundreds of homes, scores of businesses and 15 churches. Eight of those churches built new structures. Only two of the uprooted businesses were able to move and still operate today. Both are still in East Knoxville.”

However, a great source for local black history remains in Knoxville. The Beck Cultural Exchange Center, founded in 1975, serves as a repository for black history and culture in the region. Visitors can learn about prominent black citizens, the everyday experiences of black Knoxvillians, and gain a deeper understanding of American history. Appalachians have a long history of leaving their home for cities outside the region, but cities within the region have a deep history to learn from as well.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Anthony Hennen is a co-founder of expatalachians and editor/writer at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal in Raleigh, North Carolina.