Mark Ruffalo’s eco-thriller film Dark Waters goes nationwide on Friday, and the internet is abuzz. Based on true events, the film tells the story of efforts to expose a cover-up by the DuPont chemical company, which knowingly contaminated the water supply surrounding its plant near Parkersburg, West Virginia with a chemical called PFOA.

An amazing tale in its own right, the story Dark Waters chronicles is especially significant for expatalachians, as most of our team grew up in the area where the DuPont contamination took place. Many of us have experienced the negative health effects of the contamination firsthand, and all of us have witnessed the decades-long fight for justice in a community where DuPont retains significant power. For those of us affected, the movie is less a revelation than the culmination of a 20-year fight for the truth.

And yet, the fight is far from over. Although Dark Waters may make Parkersburg the best-known case of PFOA contamination, the chemical and others like it are produced all over the world, with contaminations reported in places as far away as China and Alaska. Local activists should be proud that their fight has made it to the big screen, but any accounting will show the Parkersburg saga is just the opening battle in a global war.

At first, Dark Waters’ story seems straightforward. Starting in the 1950s, DuPont dumped perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), a toxic chemical used in Teflon products like non-stick pans, into the Ohio River. DuPont did this for decades even though the company knew PFOA was dangerous to the hundreds of thousands of people who use the Ohio for drinking water. That is until a lawyer named Rob Bilott (played by Ruffalo in the film) uncovered the contamination and won a massive class-action lawsuit against one of America’s corporate giants.

The consequences of the lawsuit, however, aren’t so straightforward. Although a phaseout of PFOA in the 2000s means the chemical is no longer manufactured in the US, DuPont and other companies switched to using similar chemicals from the same family, such as GenX, that may also have negative health effects.

“The family of PFAS chemicals includes nearly 5,000 chemicals, including PFOA,” said Pamela Miller, co-chair of the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN). “After the phase-out, the companies did what we call a “regrettable substitution” and replaced [PFOA] with other PFAS chemicals,” she said.

Despite the lawsuit, things in Parkersburg also haven’t changed much. To avoid liability, DuPont spun off its Teflon divisions into a new company called Chemours in 2015, which still uses PFAS chemicals at the Parkersburg plant. “It’s still being made. They offloaded their debt. They offloaded their problems. And they’re still making it,” said Eric Engle, a Parkersburg activist and chairman of the Mid-Ohio Valley Climate Action group.

More fundamentally though, the problem Dark Waters chronicles isn’t limited to Parkersburg. PFAS chemicals, which have been linked to increased risk of several cancers, thyroid and cholesterol problems, and fetal development issues, are used throughout the country and around the globe.

“The [PFAS] problem is extensive. There are hundreds of sites where PFAS are produced or used, affecting the drinking water of 110 million people just in the US. Michigan, New Hampshire, West Virginia, as well as Chemours in North Carolina…China is now a major manufacturer of PFAS as well,” Miller said.

Communities where PFAS chemicals are produced aren’t the only ones who need to be concerned, either. PFAS-based products like firefighting foams have been linked to contaminations near airports and military bases, and recent studies have found PFAS chemicals in common food like corn, wheat, soy, tomatoes, and potatoes.

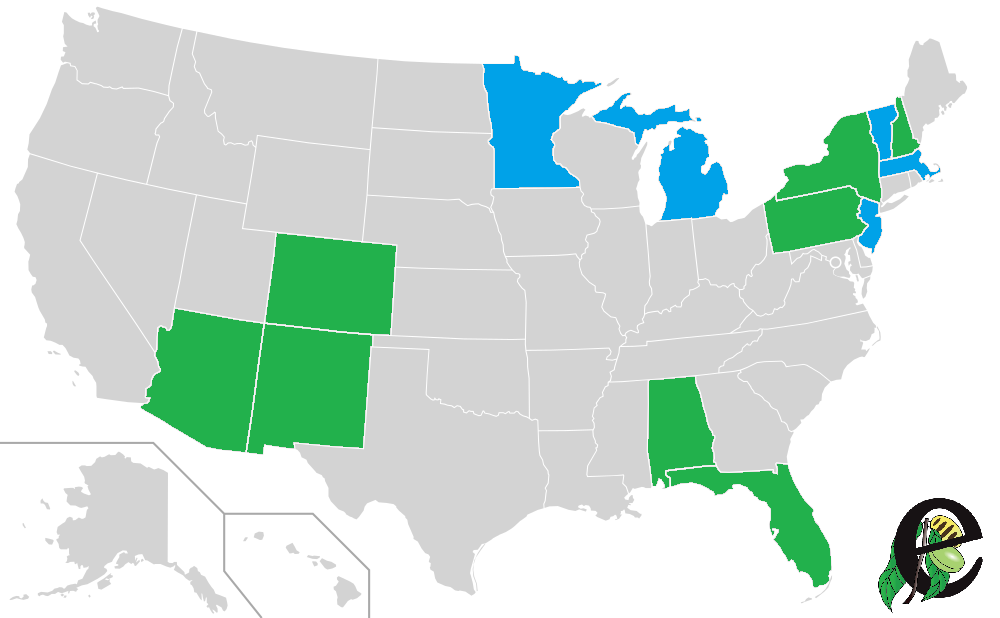

An interactive map of PFAS contamination in America by the Environmental Working Group. Click on a specific point and scroll down for more information on a particular case. Via EWG.

In her work with the Alaska Community Action on Toxics, an environmental health and justice organization based in Anchorage, Miller has seen how PFAS chemicals have made their way to the most remote places in the world.

“[PFAS] chemicals can move on wind and ocean currents and…because of prevailing currents, they move to the poles. We’ve been doing a community project with a Yupik [indigenous] community on St. Lawrence Island [125 miles from the Alaska mainland]. Ninety-eight percent of people had PFOA in their blood. Almost everyone is contaminated with these chemicals, even in communities in the Arctic where they weren’t produced,” Miller said.

Communities have responded to the threat of PFAS contamination in different ways. Several local governments have filed lawsuits against contaminators: Minnesota secured an $850 million settlement from the St. Paul-based 3M chemical company in 2018, and an Appalachian Alabama water authority won a $35 million settlement from the company in 2019. In July 2018, Michigan declared a state of emergency when the town of Parchment’s water supply registered PFAS levels 20 times higher than the recommended limit.

Despite the Trump Administration’s reluctance to introduce federal drinking water standards, several states have also moved to introduce their own PFAS regulations. “The states that are really at the forefront include New Jersey, New Hampshire, Washington, Colorado,” Miller said.

Driven in part by revelations from the DuPont lawsuit, PFAS-related activism has grown globally since the 2000s. IPEN member organization have published reports on PFAS chemicals affecting countries including Japan, Lebanon, Malaysia, India, and Vietnam, and groups opposing PFAS contamination have organized in Australia, the Netherlands, and Italy.

In May 2019, the anti-PFAS movement gained a victory when PFOA was added to the list of chemicals banned by the Stockholm Convention, a legally binding treaty that seeks to eliminate the world’s most toxic chemicals. Although significant exemptions were granted to the European Union, China, and Iran, the Convention warned countries against making “regrettable substitutions” with PFAS chemicals likely to cause negative health effects. Along with countries like Italy, South Sudan, and Malaysia, the United States is one of a dozen countries not a party to the Stockholm Convention.

Despite the publicity surrounding the Parkersburg contamination, West Virginia and Ohio have lagged behind the rest of the world in regulating PFAS. While both states have gained national coverage for their lawsuits against opioid manufacturers, neither has filed suit against DuPont, and neither has proposed state-level PFAS drinking water limits.

However, following Dark Waters’ limited release last week, a group of West Virginia legislators released a statement condemning the film’s perceived stereotyping of West Virginians.

For Parkersburg’s Eric Engle, this inaction is linked to the powerful influence of local petrochemical industries. “We have politicians still investing in petrochemicals to save the oil and gas industry…They’re wanting to store ethane here now. We’re still learning about the dangers of all these petrochemicals…We have to move past it,” Engle said.

Despite his frustrations, Engle does say Dark Waters and The Devil We Know, a 2018 documentary about the Parkersburg contamination, have changed the conversation in the area. “With all of this attention, people are seeing the harm that DuPont products did. The number one thing is we have to ban PFOA/PFAS. Any level of [the chemicals] is damaging,” he said.

As Parkersburg continues it struggle for clean water in the wake of Dark Waters, it stands to benefit from the solidarity and experience of allies around the world.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nicholas Brumfield grew up in the Parkersburg area and has close family members who were involved in the DuPont class-action lawsuit. He lives and works in Arlington, VA. For more hot takes on Appalachia and Ohio politics, follow him on Twitter: @NickJBrumfield.