A black West Virginian mother and her three children. Via West Virginia Humanities Council.

We don’t talk about race enough when we talk about West Virginia. Indeed, West Virginia is often portrayed by both outsiders and locals as an archetypically “white” state, a notion that wrongfully erases many mountaineers of color. While this trope was most recently invoked in post-2016 discussions about West Virginia’s “white working class,” nowhere is it more egregious than in West Virginians’ collective amnesia about their state’s history with slavery.

According to a traditional reading of West Virginia history, slavery had little-to-no place in the mountains. With its rugged terrain, historians often portrayed West Virginia as inhospitable to plantation agriculture and, hence, to slavery. Yes, slavery was legal, and yes, a few people owned slaves, but that was the exception. Anyway, the argument went, West Virginia was clearly anti-slavery because it seceded from Virginia during the Civil War.

This narrative continues to be taught in most West Virginia classrooms. In the most recent West Virginia social studies content standards, which represent what state officials think every West Virginian should know upon completing high school, slavery is mentioned twice: always in a national rather than state context, and always buried in a laundry list of other topics like economic development and states’ rights. Similarly, reading an 8th grade West Virginia history textbook from 2013, one could be forgiven for thinking western Virginia was a bastion of abolitionism against the slaveholding east:

Many westerners pushed for the emancipation (freeing) of the slaves. The Virginia government would not take such a step, however, because the state legislature was under the control of the slaveholders from the east….When westerners claimed slavery went against the spirit of the Declaration of Independence, easterners retorted that the founding fathers had rejected the idea of including the emancipation of slaves in the Constitution.

Simply put, this narrative is bull.

“Racial attitudes towards blacks in West Virginia were the same as they were in the rest of the South. The majority of white people in what was then northwestern Virginia thought of slavery as normal and appropriate,” said Adam Zucconi, an assistant professor of history at the Richard Bland College of William & Mary who studies white attitudes toward slavery in antebellum West Virginia.

In addition to misrepresenting mountaineers’ views, this state-sponsored narrative effectively erases slavery’s pervasive presence in West Virginia. While the state’s 5-7 percent slave population may seem small compared to states like Mississippi and Virginia, aggregate numbers hide a much larger story. Slaveholders dominated the state’s economy in the antebellum period, owning between 33-40 percent of land in West Virginia and eastern Kentucky, and they translated their wealth into disproportionate political and social power. Most insidiously, local laws required non-slaveholding whites to pay for and participate in community slave patrols. Those patrols were a highly controversial institution, mostly because it protected wealthy slave-owners’ property at public expense; nevertheless, they implicated entire communities in perpetuating slavery and generated intense racial animosity between African-Americans and lower-class whites.

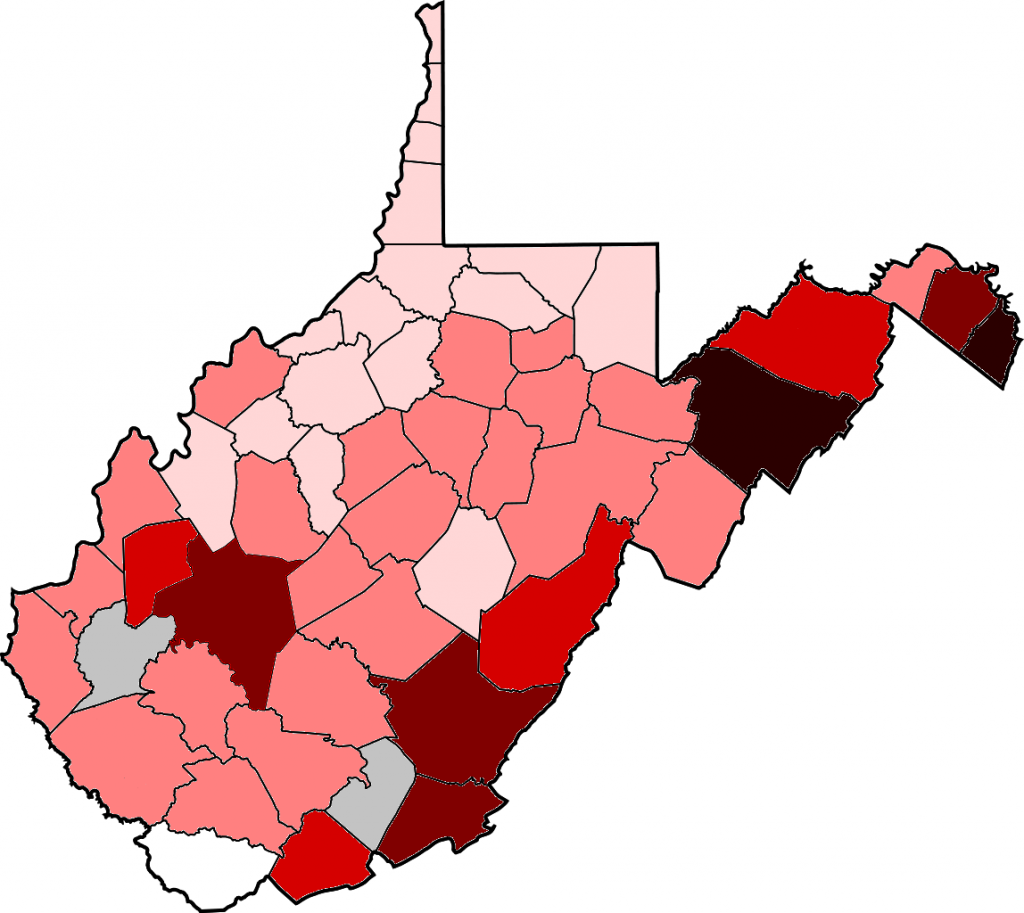

Map of West Virginia counties by percentage of slave population in 1860. White = 0 percent, light pink = <1 percent, pink = 1-5 percent, light red = 5-10 percent, dark red = 10-15 percent, darkest red = 15< percent, grey = county did not exist in 1860. Grant and Mineral counties were created out of Hardy and Hampshire counties, respectively, in 1866. They are shown here as part of their original counties. Source: West Virginia Archives & History

To varying degrees, slaves were present in all but one West Virginia county in 1860. The highest concentrations were in the Eastern Panhandle, where slaves used as agricultural labor comprised almost one-third of Jefferson County’s population, and the southeast, where the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad had recently opened the mountains to slave-based agriculture. In the north-central and southwestern parts of the state, where slave percentages were lower, slaves were used as farm hands, domestic laborers, or in service positions like kitchen servants and barbers. However they were worked, enslaved blacks constantly faced the brutal reality of slavery. “No matter how relaxed or less violent slavery might have been in certain parts of the state, the power dynamic of slavery and white supremacy was always present,” said Cicero Fain, a professor of history at the College of Southern Maryland and the author of a book on African-American Huntington.

In addition to being more pervasive than depicted in official narratives, slave labor also formed the basis of many things considered quintessentially West Virginian. Most notably, West Virginia’s capital city of Charleston first developed as a center in the slave-based Kanawha Valley salt industry. In 1850, over 3,000 slaves were employed in and around Kanawha County salt production, where they did everything from tending to the super-hot salt furnaces to mining coal in incredibly unsafe conditions. With salt furnaces running 24 hours a day, six days a week, the Kanawha Valley salt industry was so brutal that entrepreneurs preferred to lease rather than purchase slaves for the work.

Similarly, the famed Greenbrier resort in White Sulphur Springs, now known for its PGA tournament and former congressional bunker, also got its start with slavery. In fact, the entire Appalachian spa industry centered on White Sulphur Springs emerged in the mid-1800s in part as a “buy Southern” movement by slaveholders trying to escape the brutal heat of Southern summers while avoiding resorts in the abolitionist North. At one point, the Greenbrier claimed to own $56,000 worth of slaves, and large numbers of local and hired slaves were employed along with free blacks to entertain and serve the elite of Southern slaveholding society.

Booker T. Washington of Malden, West Virginia. Shortly after emancipation Washington moved with his family to Malden near Charleston, where he worked in the brutal Kanawha salt industry. Via Wikimedia Commons.

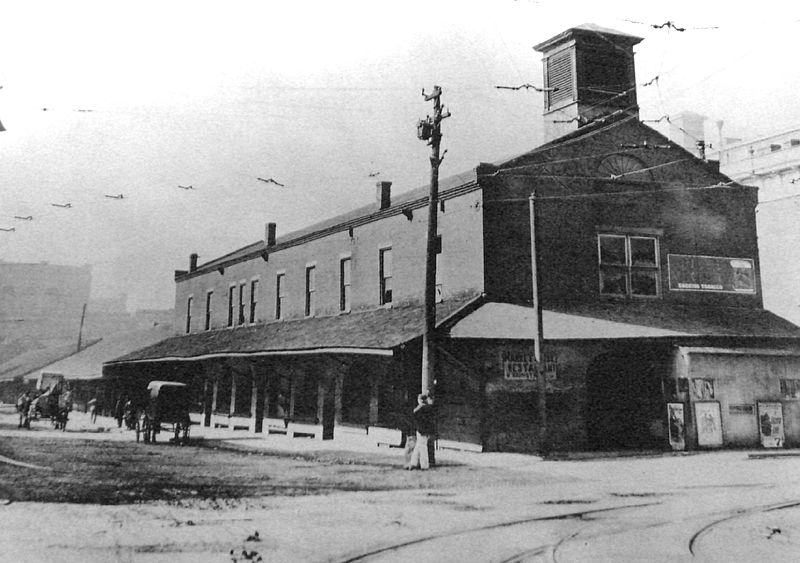

Though the percentage of slave residents varied by county, construction on important public works throughout the state also relied on slave labor. Slaves were contracted to build transportation improvements like the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad that led to the growth of cities like Clarksburg, Parkersburg, and Wheeling. Worse, those improvements made West Virginia a central nexus in America’s internal slave trade, with slaves being herded west over the mountains in large caravans. Most notably, Wheeling (then West Virginia’s largest city) was a major depot for shipping slaves from eastern Virginia along the National Road and down the Ohio River until at least 1830. While Wheeling never had a major permanent slave population, the conditions for slaves passing through the city were brutal enough to inspire famed Quaker activist Benjamin Lundy to adopt abolitionism. In this way, even the center of the statehood movement in West Virginia was implicated in the peculiar institution.

The Market House in Wheeling, constructed circa 1822. Weekly slave auctions were held here prior to the Civil War. Via Wikimedia Commons.

While documenting the nature of slavery in West Virginia remains a key goal for historians, just as important is highlighting how enslaved African-Americans were active agents in their own lives. “Despite their situation, black people exercised black agency in day-to-day life. Slaves would break tools, or go on a walkabout and just disappear for a few days to protest their condition,” Cicero Fain said. And, especially near the Ohio River, “Slaves availed themselves of escape whenever possible. Although it’s important not to mythologize the Underground Railroad, it was there, and slaves took advantage of it,” he said.

Ultimately, the most consequential form of black agency may have been what slaves did after they were freed: leave West Virginia for good. Fain noted,

The most salient point in debunking the idea that slavery was more benign in West Virginia is the massive out-migration from southern counties you see after the Civil War. People weren’t staying and being friendly with their old masters; they were getting out of dodge. I think that speaks volumes about the desire to maintain white supremacy in those areas. And unfortunately, that depopulation meant it would be another generation before there were enough black people to form the professional class needed to fight for their rights in the state.

Although much progress has been made in recent years to recover and recount West Virginia slaves’ experiences, a lot of work still needs done. There remains no memorial to slaves in the state, the traditional narrative remains strong, and West Virginians have yet to fully grapple with the legacy of slavery in their state. “There are still stories to be told,” Fain said. As expatalachians continues exploring Appalachian black history during February and beyond, let us remember that the seemingly distant history of slavery lives with us even now.

Some recommended resources on slavery in West Virginia and Appalachia:

- Slavery in the American Mountain South by Wilma Dunaway

- Appalachians and Race, edited by John Inscoe

- The Antebellum Kanawha Salt Business and Western Markets by John Stealey

- Black Huntington: An Appalachian Story by Cicero Fain

- Wilma Dunaway’s Appalachian Slave Narrative Database

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nicholas Brumfield is a native of Parkersburg, WV currently working in Arlington, VA. He is also a 2007 recipient of the West Virginia Golden Horseshoe for exceptional knowledge of West Virginia history. For more hot takes on Appalachia and Ohio politics, follow him on Twitter: @NickJBrumfield.