When folks talk about Appalachian religion, they never mention the Russian Orthodox monks. Fiery evangelical Protestantism? Check. Secretive snake-handling cults? Sure. But no monks.

Yet, for the past 33 years, the Russian Orthodox monks of Holy Cross Monastery have lived out their faith in Wayne County, West Virginia, 45 minutes south of Huntington. Running a fully functional farm while leading a contemplative life, the monks of Holy Cross are keeping an ancient monastic tradition alive in the mountains.

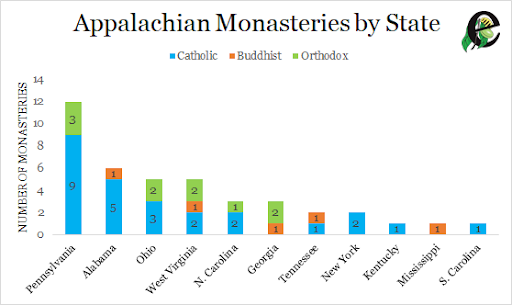

They’re not alone. Despite Appalachia’s population being predominantly Protestant, a branch of Christianity that has historically shunned monasticism, contemplative life is very much alive in the region, and more diverse than one might think. As of April 2019, Appalachia was home to at least 41 monastic communities, from Roman Catholic motherhouses to Coptic Orthodox convents and two full-fledged Buddhist monasteries.

At its most fundamental, monasticism is about separating oneself from society to live a life devoted to religion as a monk or nun. While often a labor of intense passion, the decision to set aside oneself for God is neither quick nor easy. For Sister Chiara Riffon, a native of Morgantown, WV serving with the Franciscan Sisters in Toronto, Ohio, it could even be frightening.

“I felt the call to religious life initially when I was a sophomore in high school…During the prayers of consecration, when the priest elevated the Host…I looked over and I was like ‘No!’” Riffon said, describing the feeling of God’s call. “But the Lord was very gentle. I met this religious community…during my freshman year of college and I came out and visited, and everything just seemed right. Everything just fit. It was a very difficult decision for me, but I discerned to leave college after my sophomore year, and I joined here.”

Six hundred miles to the south, in the foothills of Dawsonville, Georgia, Mother Mariam of the St. Mary and St. Demiana Coptic Orthodox Convent recounted a similar journey. Having grown up in the Coptic Church, an Orthodox Christian community from Egypt with over 10 million members globally, Mariam considered monastic life as a teenager, but didn’t commit herself until later. “I finished college, worked, and went to pharmacy school, but those thoughts remained,” she said.

Ultimately, Mariam became the first sister to join her convent after it was founded in 2011. It has since grown to 14 sisters from all over the world, with members conducting affairs in English, Arabic, and Coptic, a language descended from ancient Egyptian.

While living a “contemplative life” may seem idyllic from the outside, it is by no means a life without work. For the women of St. Mary and St. Demiana, the day begins at 4 a.m., when they wake for praise services. Then comes the liturgy at six, followed by a two-hour break at eight before work starts at ten. Every sister is expected to work six hours each day to maintain the monastery. “As St. Paul said in the Epistles, he who does not work does not eat,” Mother Mariam said.

After prayers at 5 p.m., the sisters are free from communal duties, although each still has her individual prayer obligations, which can take several hours. “There’s no firm bedtime, but the internet gets turned off at 10,” Mariam said, before the cycle begins anew the next day.

While each monastic order does its own kind of work—the Franciscan Sisters of Toronto have run a thrift store and emergency food bank for over two decades, for example—the overriding mission for all was to draw on the power of prayer. “We pray, formally, four to five hours a day,” Sister Chiara explained. “Our prayer life is always primary. And, as much as the world sees that as a waste, who’s better to waste yourself on than Jesus?”

While striving to live a more holy life, both the Franciscan Sisters and St. Mary and St. Demiana seek to engage with their surrounding communities because, for them, to be a sister is to show God’s love.

For Sister Chiara, this means connecting with people as people, even as she has her eyes fixed on God. “The number one thing I hear from people is, ‘Wow, you’re so human. You’re so normal.’ And I’m like, ‘Yep. I don’t live in this spiritual ecstasy all the time. I have joys and struggles just like you do, and issues with people. I have all these very human qualities about me,” she said.

“Although I will say I am probably more human than some. It’s probably the millennial in me,” Chiara said with a smirk. “When we do ministries, the number one thing people comment on is our sisterhood, and our fraternity. And that’s a better witness than the best talk you could ever give. And we’re not perfect by any means, but we’re all striving for holiness.”

For Mother Mariam, this means loving thy neighbor unconditionally. “The monk is an ambassador for Christ. The monastery is to be the light of the world,” she said. “A lot of people are lost. We are here to be a refuge. Many young people who’ve left the church feel they can’t come back because of the judgement. We are here to show them that God still loves them, and hopefully they can pass that hope on.”

Perhaps if folks could all be more monastic in their daily lives, we’d all be a bit better off.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nicholas Brumfield is a native of Parkersburg, WV currently working in Arlington, VA. He is also a 2007 recipient of the West Virginia Golden Horseshoe for exceptional knowledge of West Virginia history. For more hot takes on Appalachia and Ohio politics, follow him on Twitter: @NickJBrumfield.