The hills and valleys, the mountains and rivers, the villages and cities. Two-lane roads. Sunflower fields and cornfields.

Aside from the white storks (who spend winter in Africa), the distinctive shape of hay bales, and the ruins left behind by the Romans and the communists, Romania can sometimes pass for Appalachia.

In fact, along the Carpathian Mountains, Romania sometimes mirrors Appalachia in both its strengths and troubles. From its natural scenery and conservation issues to the economic reliance on coal and timber, some researchers have connected the American and European dots. Even the plants and animals in both places can be similar.

In July, a friend and I took a road trip across the northern part of the country. After a week, we had seen 93 horse-drawn carts, a jarringly traditional mode of transportation beside small European cars, and 144 white storks.

Roughly twice the size of North Carolina, Romania has about 20 million people. The Carpathian Mountains cut through the country in a backward “c” shape, filling the northern and central regions with hills and valleys. Our journey began in northwestern Romania at the city of Baia Mare, near the Ukrainian border, before turning south to Cluj-Napoca, cutting east to Iasi almost to Moldova, then west again to Bistrita and Oradea. (This article focuses on the Transylvania region, but the Carpathian range includes the regions of Transylvania, Maramures, and Bucovina in northern and central Romania.)

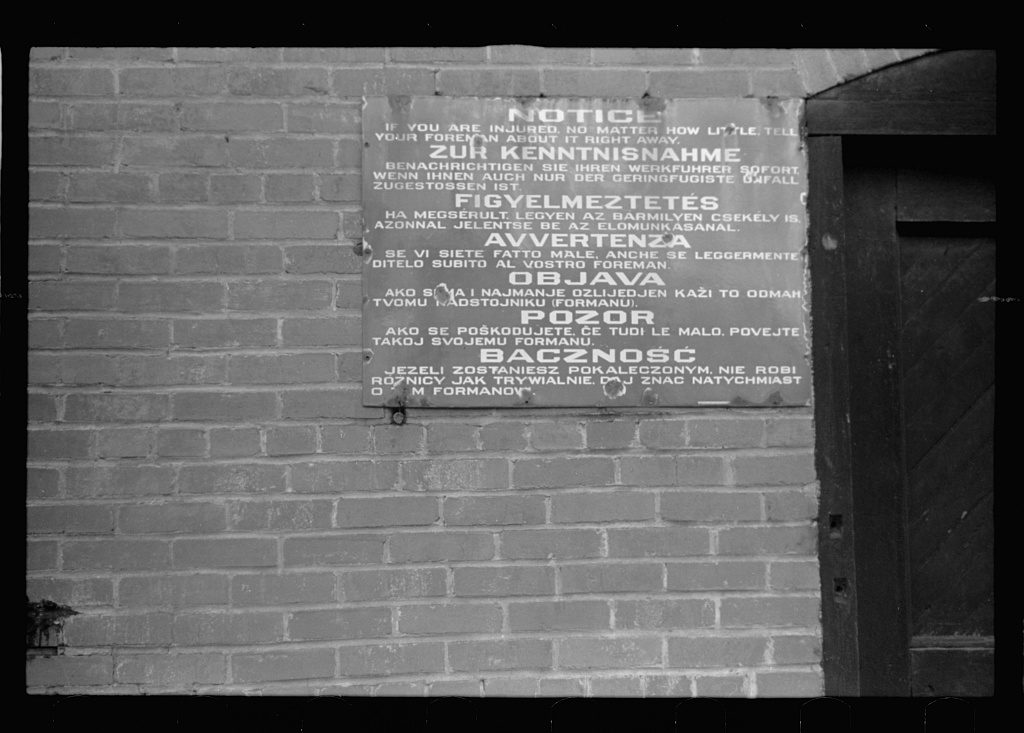

Criss-crossing the Carpathians, our route relies on two-lane roads cutting through villages where dogs and chickens freely roam. Houses have intricate wooden fences and large gardens; supermarkets are rare. Larger towns serve as hubs for gas stations, hitchhiking, and some impressive Orthodox churches. The signposts for towns are generally in Romanian, adding Hungarian and German to denote mixed areas.

Ornate signs mark some towns, many of them in concrete-brutalist or twisted-pipes styles from the communist era. Romania’s lack of interstates make the drive twice as long as it would be in America, but the scenery distracts drivers from glancing at the clock. The communists could destroy the environment just as they could the cities and the villages, but they couldn’t destroy every eye-grabbing view.

The mountains and valleys tend to be steeper and more dramatic than the Appalachians. Both, however, have hairpin turns. Inevitably, driving up a mountain gets us stuck behind a tractor-trailer. Drivers are more reckless here and whip around turns to squeeze pass the truck, gambling that no one is coming in the opposite direction. We only saw one close call. Reaching a small valley, the road follows a shallow stream, its low volume failing to deter a local fisherman.

Heading west through northern Transylvania, we wait at a train crossing in the rain. A carload of young Romanians take the opportunity of the traffic jam to smoke. After it clears, more sloping curves await us while the hills become mountains. A blue haze descends, fog hiding cattle and farmhouses. A view that formerly stretched for miles recedes to yards. Tall, rigid pine trees push their tips through the mist. With a few rays of light remaining, we reach the Tihuța Pass. Its other name, the Borgo Pass, is better-known—Bram Stoker named it so in Dracula:

It was on the dark side of twilight when we got to Bistritz, which is a very interesting old place. Being practically on the frontier—for the Borgo Pass leads from it into Bukovina—it has had a very stormy existence, and it certainly shows marks of it.

….

Then through the darkness I could see a sort of patch of grey light ahead of us, as though there were a cleft in the hills. The excitement of the passengers grew greater; the crazy coach rocked on its great leather springs, and swayed like a boat tossed on a stormy sea. I had to hold on. The road grew more level, and we appeared to fly along. Then the mountains seemed to come nearer to us on each side and to frown down upon us; we were entering on the Borgo Pass.

What Stoker doesn’t cover in nearly enough detail is the phenomenal beauty of the pass, whether traveling through by horse-coach or by car.

Few tourists make it to Romania, and it’s a shame. Tourism has grown over the last decade, but it’s driven by locals (80 percent of all tourists, according to Eurostat data) traveling within their country. Within Transylvania, the cities of Cluj and Brasov attract (relatively) big crowds, but Romania struggles to attract foreigners. (When Googling “Romania tourism,” for instance, the first question is, “Is Romania safe for tourists?”)

Ignoring the stereotypes about crime and communism, the country has so much to offer. Within a week, we visited a Roman amphitheater built from stone during the reign of Emperor Hadrian in 157 A.D., near the city of Zalau. Our only company there, in the former capital of Roman-ruled Dacia, was a young Romanian family and the ticket-seller (a $2 entry fee), who was very curious where we came from. In Bucovina, we toured a handful of 16th-century painted monasteries, built by the Romanian king St. Stefan the Great to honor God after defeating the invading Ottoman Turks. They’ve been recognized as UNESCO World Heritage sites since 1993. And in Oradea, near the Hungarian border, we took in a small city filled with well-preserved art nouveau architecture.

Though Romania has attracted few American tourists, some American academics have been attracted to the Carpathians. Over the last 15 years, a group of them have established a Carpathian-Appalachian connection to compare the similarities in the regions—their strengths, problems, and overlapping histories.

“For the past decade, the collaborations have focused largely on mountain cultures and sustainable economic development. We have also addressed numerous shared ecological problems, including deforestation and shale fracking,” Dr. Donald Edward Davis, an independent scholar who has written widely on Appalachia and served as a Fulbright scholar in Romania and Ukraine, said in an email.

Collaboration has meant working together on academic research, as well as hosting European students and professors at Appalachian universities.

“The similarities between the Appalachians and Carpathians are hardly superficial,” Davis said. The forests have spurred economic growth early on in both places. Towns and cities tended to get built in valleys along major rivers. Even gardens in both regions look similar: Carpathians added corn, tomatoes, and potatoes from North America into their diet while Appalachians started to grow buckwheat, apples, and wheat from Europe, he noted.

A uniquely Appalachian plant also connects the regions: ramps. In the Carpathian range, though, they’re picked differently.

“Carpathian ramps (Allium ursinum) are harvested in both Ukraine and Romania in the early spring, but most ‘pickers’ leave the bulb in the ground, which allows the plant to resprout the following spring,” Davis said. “In Appalachia, most folks dig up the entire plant, which as ethnobotanist Sunshine Brosi (Frostburg State University) has argued, is an unsustainable practice. Sharing this knowledge with Appalachians could help preserve mountain ramp populations.”

If Carpathian growers copy the ramp festivals held in Appalachia, Davis added, it could help them spur some economic growth as well.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, thousands of Carpathian natives immigrated to Appalachia to work in coal mines and steel mills, as Lou Martin, a labor historian at Chatham University in Pittsburgh, has documented.

In October, the 4th Appalachian/Carpathian International Conference will take place in Braşov and Petroşani (a hub for coal mining), to trade ideas on the theme “Making Place: Transitional and post-Industrial Development in Mountain Communities.”

“We are hoping the conference will help establish additional connections between the two mountain regions,” Davis said. “Particular questions to be addressed at the conference include 1) how to survive in a post-coal economy, 2) using the cultural arts, tourism, local agriculture, and the natural environment as drivers of local economic development.”

The connection matters for another reason: working together might spark some ideas for how to keep more young people from leaving both areas. When I stopped in Cluj, the 4th-largest city in Romania, I had dinner with an economist who described the Romanian political system as one that is designed to push people out of the country.

Young, ambitious Romanians who don’t like the status quo have a difficult time if they try and change it. Corruption remains a problem, even after an ambitious fight to clean up the political system, and moving to western Europe can double or triple a worker’s wages. The appeal to improve their lives by leaving to earn a living for their family abroad, and dodging the corrupt bureaucracy holding back the country, is obvious.

The problems that face both regions can be extremely difficult and lack easy solutions. However, getting to know another place an ocean away might help locals see home in another light. And find ways to make it better.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Anthony Hennen is a co-founder of expatalachians and managing editor at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal in Raleigh, North Carolina.