Far from the glitter and glamor of Windsor Castle, a recent episode of Netflix’s The Crown takes place in the coal-producing South Wales Valleys region. In a dark departure from the royal family intrigue that fuels the show, the episode features the Queen’s response to the Aberfan Disaster in 1966, which killed 144 people.

On a Friday morning in October, a coal slag heap built on a mountainside became unstable, causing a partial collapse and releasing millions of cubic feet of sludge into the Aberfan village below. The fast-moving sludge destroyed several houses and an elementary school, killing 109 schoolchildren as they began their daily lessons. A tribunal inquiry found the National Coal Board (the governmental operator of British coal mines) at fault. Citing ineptitude, ignorance and a lack of communication, the inquiry found that, “the Aberfan disaster could and should have been prevented.”

Included in the tribunal’s report was a series of findings, recommendations, and necessary legislation to prevent another tragedy. Those findings, and the horror broadcast in international media, spurred preventative efforts across the Atlantic, too. Within months of the Welsh disaster, the U.S. Geological Survey sent geologists and hydrologists to 38 dams in central Appalachia that could cause a similar catastrophe. This included a dam in Logan County, West Virginia that held a pool of coal slurry in Middle Fork, a tributary of Buffalo Creek.

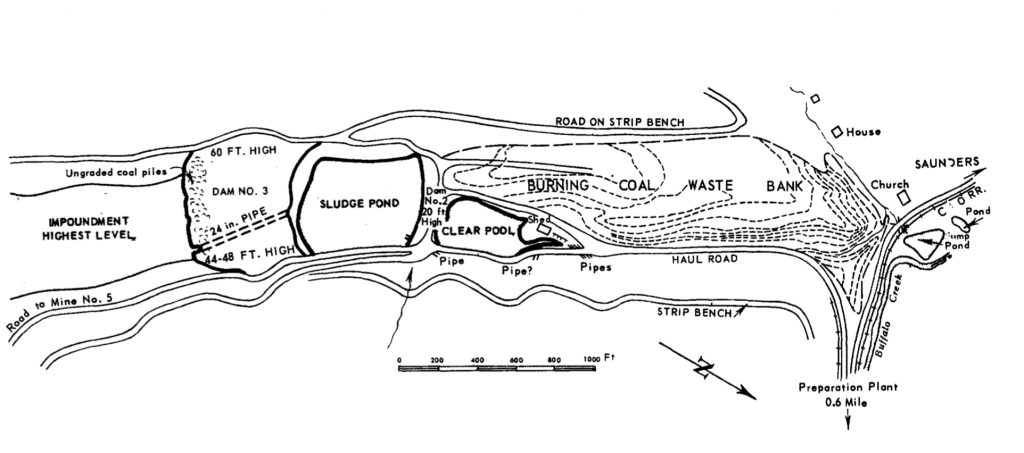

Calling it a “dam” is somewhat grandiose. Termed “impoundments” by the Pittston Coal Company that built it, the original structure was a pile of coal slag (the waste product of coal production) and scrap to restrain the heavily polluted Middle Fork. It served two functions: To keep the state Department of Environmental Protection happy by keeping the coal waste from flowing into Buffalo Creek, and to provide a dumping ground for the tons of slag produced in the nearby mines. Within a few years of the 1966 visit from the USGS, the dam had already ruptured and caused minor flooding.

By the end of the decade, two more slag heaps-turned dams had been built on Middle Fork after the initial one failed. Overlooking the town of Saunders and the narrow Buffalo Creek hollow, the largest of dams had impeded the flow of Middle Fork to the point that a small lake had formed behind it.

While those refuse impoundments were not uncommon in the Central Appalachian coalfields, they were not intended to hold back stagnant bodies of water. Most only held water in extraordinary times of rainfall or during the spring thaw. The large top dam failed in 1971, but the water was held by the middle dam. Though fines were levied by the state, no investigations were ever initiated.

In late February 1972, southwest West Virginia received heavy rainfall, a normal occurrence for the season. The water in the lake above Middle Fork rose steadily throughout the night of February 25 as the coal company watched; workers regularly measured the depth and they quickly cut a spillway early on February 26. The company assured local authorities that the problem was taken care of, and they sent no warning to the community of Saunders and the thousands of other residents in Buffalo Creek hollow.

Then, at about 8 a.m. on February 26, the dam became inundated with water and collapsed. It is not definitively known if the lake crested the dam or if the structure simply became a soggy mess and fell apart. Regardless, within minutes, 132 million gallons of water from the lake roared down Middle Fork, pulverizing the other dams and creating a garbage and slag-filled sludge that engulfed Saunders.

Unlike Aberfan, in which the sludge descended upon a single village and stopped at the bottom of the valley, the Buffalo Creek Flood contained the volume of a small lake. The sludge of mud, water, coal refuse and now the buildings of Saunders, rushed through Buffalo Creek hollow and flooded 17 communities, destroying many of them. In total, the flood killed 125 people, injured more than 1,100, and left 4,000 homeless.

After the Buffalo Creek disaster, West Virginia Governor Arch Moore called for an inquiry. While critics questioned there committee members (four of the state officials were directly involved in the disaster), the Pittston Coal Company was blamed for the dam’s failure and floods.

In both the Aberfan and Buffalo Creek disasters, the coal operators took the blame. In neither case, however, did the offending party fully accept the responsibility. The National Coal Board, a government-run company, initially offered £50 (approximately $800 today) to each bereaved family, eventually increasing the offer to £500. Additionally, the British Government forced the Aberfan Memorial Fund to contribute £150,000 toward removing the six remaining slag heaps looming over the village.

The situation was similarly bleak in West Virginia. Pittston Coal set up a claims office in Buffalo Creek, settling with most victims for the then-statutory $10,000 maximum for wrongful death. A class-action suit was filed in federal court, which was eventually settled for only $13.5 million in 1974. The state filed a suit for $100 million in compensatory and punitive damages for the destroyed state property, which was secretly settled by Governor Moore in 1977 for $1 million shortly before the end of his term. Nor was Moore’s last-minute sweetheart deal his only transgression: After requesting help from the Army Corps of Engineers to clean up the disaster site, Moore refused to pay the $3.7 million bill. The unpaid bill became a decade-long legal battle, culminating in a U.S. Supreme Court Decision that ordered West Virginia to pay $10 million interest in addition to the initial $3.7 million.

It was not until 1989 that the state finally paid the Army a reduced amount of $9.5 million.

The effects of those disasters remaking in the valleys they flooded and the minds of the survivors. A 2003 article in the British Journal of Psychology found that residents of Aberfan are three times more likely to experience PTSD than survivors of similar trauma in other communities. While funds were raised to help rebuild the school and provide financial assistance to the families, no counseling was ever offered to the survivors of the Aberfan disaster.

Much of the same is true in Buffalo Creek. Sociologist Kai T. Erikson studied the after-effects of the disaster in her book Everything In Its Path, and concluded that the residents of the hollow suffer from two disasters: the “gradual deterioration of mountain culture” and the events of February 26, 1972. Ultimately she found that the flood destroyed the buildings and wreaked havoc upon the communal bonds that held their inhabitants together.

Tragically, these two disasters occurred during what would otherwise be part of the surrounding communities’ golden ages. The coal mine near Aberfan was shuttered in the late 1980s, and today Aberfan sits in one of the most economically depressed regions of the United Kingdom. Coal is still mined in Logan County, but the number of employed miners and short tons mined has both fallen precipitously.

Hardly sets for a regal costume drama, these two traumatized communities exist in the harsh reality of postindustrialism: Longing for the days when coal was king despite its destructive wrath.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nick Musgrave first became fascinated with West Virginia’s history while growing up in Parkersburg. He continues to read, research and write on the Mountain State’s past from its birthplace in Wheeling. For more neat history and some political snark, follow him on Twitter: @NickMusgraveWV.