As the very name of this publication implies, there is a sustained exodus from Appalachia. Throughout the ARC-defined region, only the southernmost subregions have grown over the past few decades. This is especially true in West Virginia, one of only three states to lose population in the 2020 census.

This is hardly news to anyone who pays any attention. WV Public Broadcasting launched their “Struggle to Stay” series in 2017, and the trend of young people leaving the Mountain State has only become stronger in numbers and narrative.

What is new (perhaps due to the census) is the growing number of initiatives to bring people, especially young people, into the region.

The biggest, flashiest, and most publicized of these is Ascend WV. The program is an effort between Governor Jim Justice, former Intuit CEO Brad Smith and his wife Alys, and West Virginia University. Those accepted into the Ascend program will receive a $12,000 stipend for moving to West Virginia, though applicants have to be fully employed and able to work remotely. To sweeten the deal, the program has given thousands of dollars’ worth of free outdoor recreation passes for participants.

Via WV Office of the Governor.

There are some quirks, however.

For one, the initial cohort is limited to Morgantown, though applications to relocate to Lewisburg or Shepherdstown are expected to open in 2022. The program is also aimed at remote workers; while that’s great, it does not help fill the need for more workers for jobs located in the state.

But with a state that has seen five-figure population declines annually for the past five years, beggars can’t be choosers.

In fact, the opportunity to attract remote workers after the plague era has inspired other communities around the Mountain State to make their pitch. Groups in Charleston, Wheeling, and Fairmont have all started to market their cities as a great place to work remotely while living and playing locally.

Created by the City of Charleston and the Charleston Area Alliance, the Charleston Roots program offers a $5,000 relocation credit for whoever moves to Charleston from outside of the city’s 50-mile radius. The program is also open to workers who work onsite in Charleston as long as they fill a “high-demand job within Charleston’s key industries.” For families of the Kanawha Valley’s expatalachians, there is also a $1,000 bonus for recruiting an accepted applicant to relocate or return home to Charleston.

Though not currently offering any financial incentives, the Marion County Chamber of Commerce has begun to promote the Fairmont area through its Marion Remote project. The initiative seeks to attract remote workers by pointing to the quality of life and low cost of living in Marion County, while also reminding potential newcomers of the “blazing fast internet providers.”

Wheeling Heritage, a community development organization, has unveiled their “Wheeling: Live Here” campaign, which includes a detailed resource guide for newcomers whether they work remotely or not. The online guide provides a central source for discovering the community’s neighborhoods, shops, and eateries, as well as information on cost of living and basic demography. They have also used their Weelunk online magazine to highlight stories of others who have moved to the city.

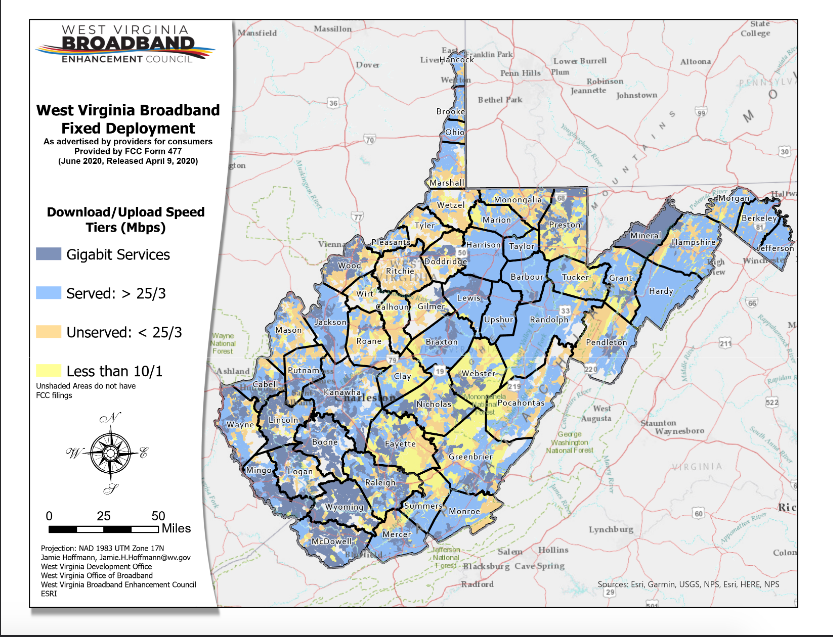

While these initiatives vary in some ways, there is one thing that they all share: broadband internet. The issue of bringing faster internet speeds (above 25 mb/s) has long plagued economic development in the state’s rural areas and smaller towns.

While the lack of internet infrastructure is concerning, one upside is the renewed wealth of social infrastructure for new residents. As a kid (and newcomer), I often joked that West Virginia was similar to Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, an insular place where “nobody ever goes in, and nobody ever comes out.” That is certainly not the case today.

Organizations like Generation West Virginia and its regional affiliates offer long-time locals, newcomers, and repatriated expatalachians alike opportunities to meet one another and their community. The organization also oversees the Impact Fellowship, a competitive program that recruits young talent to the Mountain State, matching them with host employers across various industries. Since 2017, the Impact Fellowship has placed 39 individuals, approximately 80 percent of whom stay in the state after the fellowship ends.

As is often the case, there is more to the story of why people migrate in or out of a region. Despite the relocation programs, none of my expatalachian friends have any intention of moving back home. That small sample size is anecdotal, but it is an important reminder that it takes more than cheap housing and low taxes to attract and retain young residents. Diversity, equity, and inclusion also need to be part of the conversation, as does the quality of life–not just cost of living—if we want a real shot at stopping depopulation.

But I do firmly believe that attracting as many remote workers and new residents as possible is a step in the right direction. Whatever brings people in at first.

At expatalachians, we’ve written extensively on what brought migrants to Appalachia, what caused many of them to leave, and where they ended up. While the current population loss will likely not be stopped in the short term, the renewed focus on attracting new residents gives hope to a future of migration and not emigration.

Who knows: Perhaps a few of them will get together one night, start chatting about their experience of moving to West Virginia, and start a website called Implantalachians.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nick Musgrave first became fascinated with West Virginia’s history while growing up in Parkersburg. He continues to read, research and write on the Mountain State’s past from its birthplace in Wheeling. For more neat history and some political snark, follow him on Twitter: @NickMusgraveWV.