A Brief History of Sugar

The ability to consume as much sugar as we please is often taken for granted. However, the mass production of sugar is a recent phenomenon and it began with the British arriving in the Americas.

The first English colony in the Americas was in Virginia. Shortly after, in the 17th century, they expanded into the Carribean. Trying to make a profit from the fertile Carribean soil, the Englished introduced sugarcane from Brazil. The plant thrived and proved more profitable than cotton or tobacco.

The expansion of the sugarcane industry required a large workforce to work on plantations. Instead of doing the laborious and dangerous work themselves, the English enslaved Africans. This abhorrent labor system was further fueled as the demand for sugar grew and prices fell. The unpaid labor meant consumers, rich and poor, could afford to purchase sugar an ocean away.

It wasn’t until 1795 when a sugar planter processed the first sugar crystals that sugar plantations exploded in the U.S. Louisiana became the epicenter, or as The New York Times put it, “Louisiana led the nation in destroying the lives of black people in the name of economic efficiency.” The legacy of this horrific period lingers in the pervasiveness of racism in American society today. The unquenchable appetite for sugar is another everlasting impact.

Today’s sugar industry has stopped using the labor of enslaved people, but it is far from perfect. NPR reported that the sugar industry has influenced biased academic research and promoted increased sugar consumption (despite knowing it is harmful to human health) in emerging markets. The corporate interest in sugar has also resulted in environmentally damaging production methods, such as deforestation.

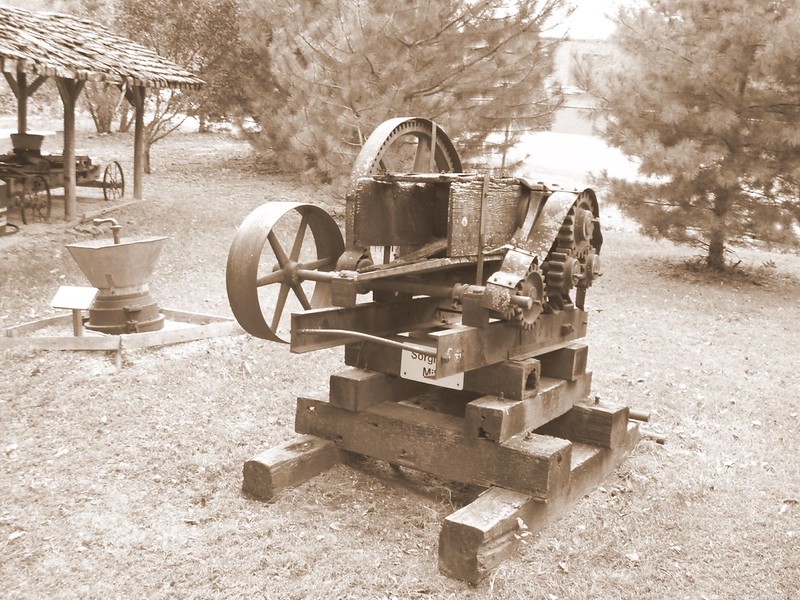

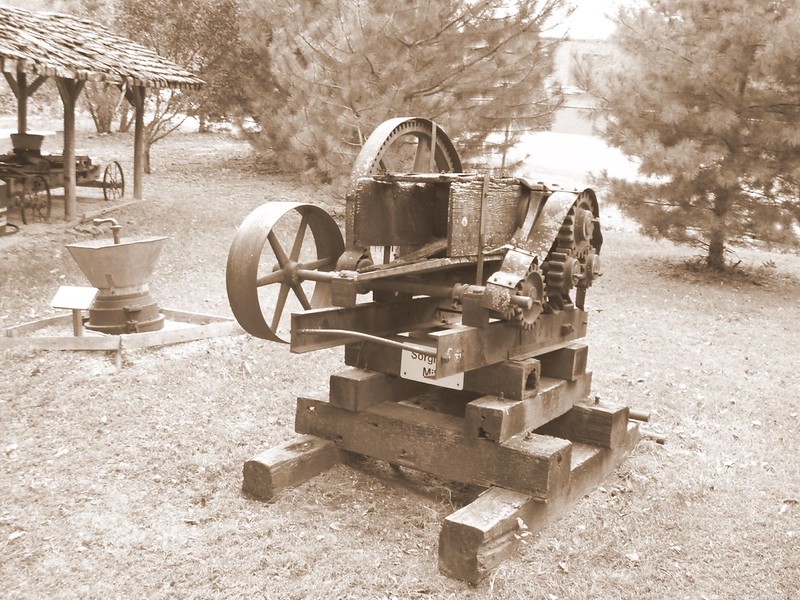

Sorghum as a Sugar Alternative

Like sugarcane, sorghum is a member of the grass family. Sorghum, however, has the ability to grow in colder climates than sugarcane, which requires a warm, tropic or subtropic climate.

Sugarcane is a perennial crop, meaning that it lives for more than two years. Some varieties of sorghum are perennials (Sorghum halepense, or Johnsongrass) but many are annuals, completing their lifecycle in one growing season. This is the case for sweet sorghum.

Sorghum differs further from sugarcane in its use as a grain. In fact, the U.S. is the world’s largest producer of grain sorghum. The drought and high heat tolerance of sorghum make it ideal to grow in dry areas of America from South Dakota to southern Texas. Sorghum arrived in the Americas with enslaved peoples from Africa. It was (and still is) used to feed livestock and animals, in addition to humans. The arrival of sweet sorghum, which differs from the grain-cultivated variety, didn’t occur until the 1850s when it was introduced from France.

Steve Patterson, executive secretary of the National Sweet Sorghum Producers and Processors Association (NSSPPA), explained that when Europeans first started to explore the world they were introduced to sorghum—which at that point had traveled through trade from Africa to India and China—and brought it back to Europe. The French, in particular, saw sorghum’s sugar-making potential. Tired of paying the high transportation cost for getting refined sugar from the Western Hemisphere to Europe, they wanted an alternative.

From the 1850s onward, sorghum syrup was being produced in America. During times of sugar shortages, such as post World War I, the demand for sorghum syrup grew. Today, however, “Sorghum is a niche market. There are not many people who make Sorghum,” Mark and Sherry Guenther of the Tennessee-based sorghum syrup company Muddy Pond, said.

Patterson echoed this sentiment, elaborating that it is hard to quantify the number of sorghum makers because many are small producers, usually families just making a few gallons. The geographic concentration of these niche producers is primarily in the southeastern U.S., notably in Kentucky and Tennessee.

A Versatile Product

In Tennessee, Kentucky, and the Carolinas, the name is sorghum molasses, rather than syrup, Patterson explained. “Technically, molasses is a byproduct that’s leftover from refining sugar and molasses has a sharper, stronger, stouter taste,” he said.

Whether it’s called molasses or syrup, there is no difference in the final product. What does make a difference is the season and production process. These factors change the flavor and texture greatly. It can have a thicker, deeper flavor or a more watery, light-flavored syrup depending on how the crop was grown and processed.

“This year most of the sorghum makers are making exceptional syrup because of the dry, hot weather we had late in summer and early fall,” Patterson said. The hotter temperatures help the accumulation of sugar.

Regardless of the seasonal variations in the flavor profile of sorghum syrup, it goes well with a variety of dishes.

“More chefs are using Sorghum syrup in their dishes. More people are using Sorghum syrup to make ice cream, granola, barbecue sauce, even dog treats,” said Mark and Sherry Guenther. A few tablespoons in a bowl of chili is the way Patterson prefers it. Green beans, stews, pancakes, and biscuits are also great companions for the syrup.

More Fun Facts About Sweet Sorghum and Sorghum Syrup

- Sorghum is planted around May or June. Around September or October, the cane is ready to harvest. At Muddy Pond, they process that cane, right after harvest, into syrup.

- When growing, sorghum resembles corn. Sweet sorghum grows particularly high, between 10-15 feet tall.

- There is great potential in sweet sorghum for biofuel. Compared to corn (used for ethanol), sweet sorghum requires fewer inputs in the growing and production process. It requires less water and doesn’t require as many conversions to get to the fuel grade alcohol stage that corn does.

- Both Patterson and the Guenthers hailed the nutritional benefits of sorghum syrup.“It is high in minerals, particularly in trace minerals. Its a source of protein, no other sweeteners are,” said Patterson. “We like Sorghum because it tastes good and has iron, potassium and other nutrients in it,” said Mark and Sherry Guenther.

Annie Chester is a writer and co-founder of expatalachians. She writes about the environment and culture in Appalachia and abroad. She is currently a postgraduate student at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.