Economic development and environmental protection can seem like opposing forces. But sometimes, restoring the environment can go hand-in-hand with economic progress—if common risks are avoided.

A recent example is a new report that wants to make reclaiming former mine lands in central Appalachia an economic opportunity. Released by the Reclaiming Appalachia Coalition (RAC), an umbrella group of non-profit organizations, it highlights 20 projects that could serve as models for rejuvenating mined lands in Ohio, West Virginia, Virginia, and Kentucky.

A $38 million investment, the report argues, could produce almost $84 million in total economic output and create more than 500 jobs. If states and the federal government get serious about restoring mine lands, the initiatives “could be Appalachia’s new New Deal.” Funding mine reclamation projects would come from the Interior Department’s Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE), which already has over $2 billion available for this purpose.

Doing so could mean hundreds of small-scale projects. The OSMRE keeps the most comprehensive catalog of abandoned mine sites, which number in the thousands, but many more exist. The projects highlighted by RAC focused on mining sites “that had some community momentum behind them,” Joey James, a senior strategist at Downstream Strategies (one of RAC’s member organizations), said in an email. “Coal mining is not limited to the larger towns and cities and while we look for economic alternatives to replace what was once our dominant way to make a living, we need to be inclusive of both rural and urban Appalachia.”

To make those economic alternatives a reality, connecting rural entrepreneurs to capital is crucial. “We are making a concerted effort to expand our philanthropic and venture-capital circles so that we can facilitate those types of connections with community organizations that are proposing projects,” James said. Otherwise, mine reclamation is a one-off effort that might be appreciated, but can’t generate long-term growth.

James emphasized that RAC chose projects that could be viable without grant money. “Basically, there has to be a plan in place for if/when the grant money isn’t there,” he said. The chosen projects needed to be innovative, involve community stakeholders, and be a potential model for future projects. Fund those small projects, show that they can sustain themselves in Appalachia, and then replicate at other sites.

That emphasis on small projects is a welcome change. Larger-scale projects, such as prisons, have failed to deliver on their promises. Most highlighted RAC projects, in contrast, are small and focused on community engagement.

“I’ll tell you right now, the projects featured in the report won’t fix all of Appalachia’s economic woes, and we need to be careful not to promise that. However, they can surely be part of the solution,” James said. “A wise person once told me, ‘Appalachia doesn’t need a silver bullet. We need 1,000 silver BBs.’”

And RAC has cast a wide net to find those BBs. Eight projects focus on tourism (from building hiking trails to expanding a “mountain resort”), four are for agriculture, three are for energy projects, and a few are business and waste management projects.

However, these projects may be light on long-term growth opportunities.

“If you look at the rural communities doing relatively well at the present time, many of them do have a strong reliance on recreation and tourism,” said David Brown, an emeritus professor of development sociology at Cornell University. “But the high majority of jobs in tourism are low-wage, low-skill jobs that do not have career ladders.”

Brown also noted that “urban-oriented agriculture” can be promising, as farmers can direct-market their crops. But with many mine sites isolated from small towns, an agriculture revival may be difficult, and the overall economic impact of these projects may be limited as well.

And while the $84 million estimate sounds encouraging, predicting the economic impact of such projects is tricky. “Generally, our competitive economic climate means that even well-designed economic impact studies almost always overestimate benefits,” Greg Halseth, a geographer at the University of British Columbia, said in an email. The longer a project takes to develop, he noted, the less likely it will live up to the optimistic numbers.

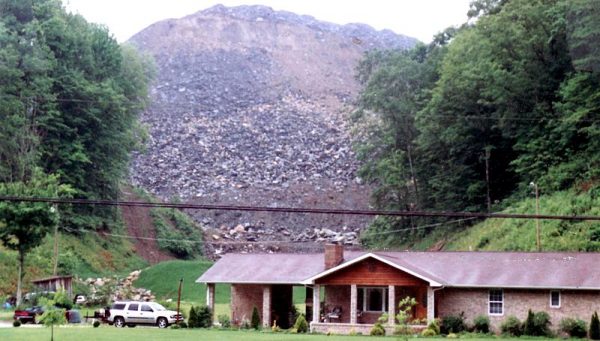

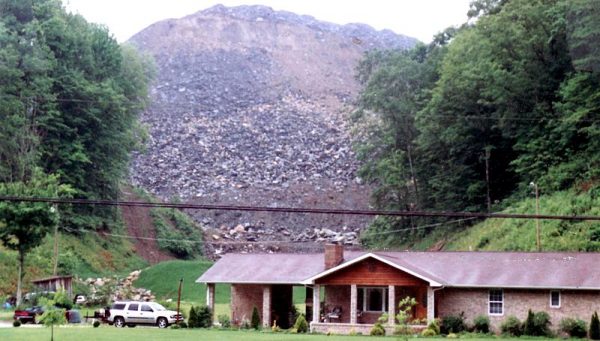

The risk of reclamation projects going bust lingers, too. Indeed, when the government pushes a large project like developing high-speed internet in Appalachia, it can waste hundreds of millions of dollars and crowd out private businesses. Many of the formerly mined lands are far from population centers and ill-suited to economic development—even if they weren’t environmentally damaged.

“The test for any policy aimed at promoting long-run economic growth is—when less money is available from the government or the money goes away entirely—if the individuals, institutions, and culture that remain in a place create self-sustaining growth on their own,” Taylor Jaworski, an economist at the University of Colorado at Boulder, said in an email. Spend those $2 billion of OSMRE funds unwisely, and it could worsen the long-term economic situation of locals. Creating ephemeral growth isn’t the difficult part; making the growth viable is.

And Jaworski’s previous research found that spending can have unintended consequences. When the federal government funded the Appalachian highway system, Jaworski and co-author Carl Kitchens found that “many of the benefits accrued to counties outside of the region targeted by the [Appalachian Regional Commission.].” Like coal profits, much of the benefits from highways didn’t stay within Appalachia.

As the economist Andrew Isserman noted in a 2009 study on prosperity in rural counties, these places tend to “have a robust private sector, diverse industries and farming, educated populations, higher incomes, strong social capital, more creative class occupations, and stable populations.” While redeveloping mining lands may play a small role in long-term prosperity for Appalachian counties, research suggests that private entrepreneurship, an educated populace, access to capital, and civic life that encourages people to stay are bigger issues.

But questionable economic payoffs does not mean restoring mine lands is foolish. The $2 billion of funds from OSMRE are already collected. And, for mine sites that cause environmental harm like acid mine drainage, it’s incumbent upon governments to take action for public health.

Funding mine reclamation projects goes beyond economics. Doing so is about making these rural communities attractive places to live—and taking sides in the debate about whether to support them. As David Brown said, “there’s a big disagreement among social scientists over whether it’s important to provide assistance to these localities…or let them dry up.”

Agriculture is a lifestyle as much as an economic choice. Brown criticized the “what you’re doing is throwing money down a rathole” view that is popular among economists when discussing rural spending. Instead, he argued that those places have “social and personal value to residents” and should not be seen as a profit/loss problem. A kinder interpretation of the economic point of view comes from Jaworski: “Policymakers should aim to help people not places.” Not all rural communities can be preserved, and some may have to fade away so others can succeed.

But this debate is not new. Appalachia—and rural areas—have previously experienced economic transitions from agriculture to manufacturing and manufacturing to service-sector jobs. Rural economies are ever-changing, and adjusting to present circumstances will remain an issue for the future.

If nothing else, embracing mine reclamation would show that state and federal governments haven’t forgotten about Appalachia. That so many mine sites still need restored show “a lack of political will and resources,” James said, but an effort to do so could signal interest in creating “sustainable patterns of specialization and trade” in rural areas, as the economist Arnold Kling describes it. Talk of an “Appalachian New Deal” may be misleading hyperbole, but it calls attention to the unintended consequences of the past. Addressing those consequences may not radically change the region, but it could encourage some young people to stick around and change what a government program cannot.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Anthony Hennen is a co-founder of expatalachians and editor/writer at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal in Raleigh, North Carolina.