Editor’s note: To celebrate Women’s History Month, expatalachians will publish a series of stories focusing on Appalachian women throughout March.

Recognized globally for her writing, Rachel Carson’s work has shaped environmental policy and imaginations worldwide. The book Silent Spring made Carson a household name, though it was not her first work. Published in 1962, Silent Spring was groundbreaking, detailing the negative impacts of synthetic pesticides, namely DDT, on the environment.

However, I want to call attention to another masterpiece: Under the Sea-Wind. The book details the beauty and tragedy of life in and around the sea. I did not hear of Under the Sea-Wind until this year, despite learning about Carson at various points in my education. That lack of knowledge for many people is understandable since Silent Spring “altered the course of history” and “influenced the environmental movement,” as The New York Times wrote. However, Silent Spring came several years after Carson garnered acclaim for other works, including Under the Sea-Wind and The Sea Around Us.

Under the Sea-Wind was Carson’s first book. Although it struggled to gain attention when it was first published due to the onset of World War II, Under the Sea-Wind eventually made the New York Times best-seller list.

Carson’s journey to acclaimed author and environmentalist started with humble beginnings. She was born in a cabin in Springdale, Pennsylvania, just outside Pittsburgh, in 1907. Inclined to academics, Carson attended Pennsylvania College for Women (today Chatham University) in 1925 to study English before changing to biology. Her excellent marks secured her a full scholarship for a master’s degree in zoology at Johns Hopkins University.

In 1935, she secured a job at the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries. In her part-time position, Carson created radio program scripts about marine life and wrote brochures for the department. When she submitted a brochure about marine life to the bureau chief, he rejected it, urging her instead to submit it to The Atlantic Monthly. It was the early draft of Undersea, which The Atlantic published and later became Under the Sea-Wind. By 1937, Carson had a full-time position as a biologist at the Bureau of Fisheries.

During her 15-year career in federal service, Carson found the time to research and write a variety of nature writings. Her literary side-hustle supported her family and eventually allowed her to move to Maine in 1953 to concentrate on writing full-time. In 1957 she began writing Silent Spring.

There are so many more interesting details about Caron’s life that I am leaving out of this story. Luckily, there is a biography, Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature that gives a more detailed account. Additionally, Always, Rachel: The Letters of Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman, 1952–1964: An Intimate Portrait of a Remarkable Friendship is a collection of letters exchanged between Carson and Dorothy Freeman, a close friend, that reveals Carson’s personal side.

Under the Sea-Wind reveals Carson’s literary genius. Through clear language, personification, and vivid description, she brings the ocean to us on land. Under the Sea-Wind is the deepest immersion in the sea without going scuba diving.

What I love most about Under the Sea-Wind is how Carson narrates death (or the cycle of life) and the human entanglement in it all. Carson’s accounts of death convey the devastation and destruction along with its beauty. “For in the sea, nothing is lost. One dies, another lives, as the precious elements of life are passed on and on in endless chains,” she writes.

Carson reframed death as a necessity of nature. Death gives life to the living:

When he [ghost crab] saw the fisherman walking across the beach he dashed into the surf, preferring this refuge to flight. But a large channel bass was lurking nearby and in a twinkling the crab was seized and eaten. Later in the same day, the bass was attacked by sharks and what was left was cast up by the tide onto the sand. There the beach fleas, scavengers of the shore, swarmed over it and devoured it.

Every creature is vying for survival and one creature’s demise is another’s victory. Each death sustains life, beginning with the smallest life forms. The endless chain of life and death (or death and life) is mundane and dramatic at the same moment:

Meanwhile the fish, drained of life by separation from water, grew limp as all its struggles ceased. Like a mist gathering on a clear glass surface, a film clouded its eyes. Soon the iridescent greens and golds that made its body, in life, a thing of beauty had faded to dullness.

The imagery here forces the reader to imagine the fish and watch the life drain from its vibrant and elegant form. There is sadness and beauty in death, but there is also violence, particularly at the hands of humans:

The grebe soon drowned. Its body hung limply from the net, along with a score of silvery fish bodies with heads pointing upstream in the direction of the spawning grounds where the early-run shad awaited their coming.

The vivid description of the grebe, a bird that resembles a duck, strangled by a fishing net is jarring. The suffering of this accidental death was a result of human negligence. The grebe is one of several instances of the literal human-nature entanglement that Carson describes in Under the Sea-Wind.

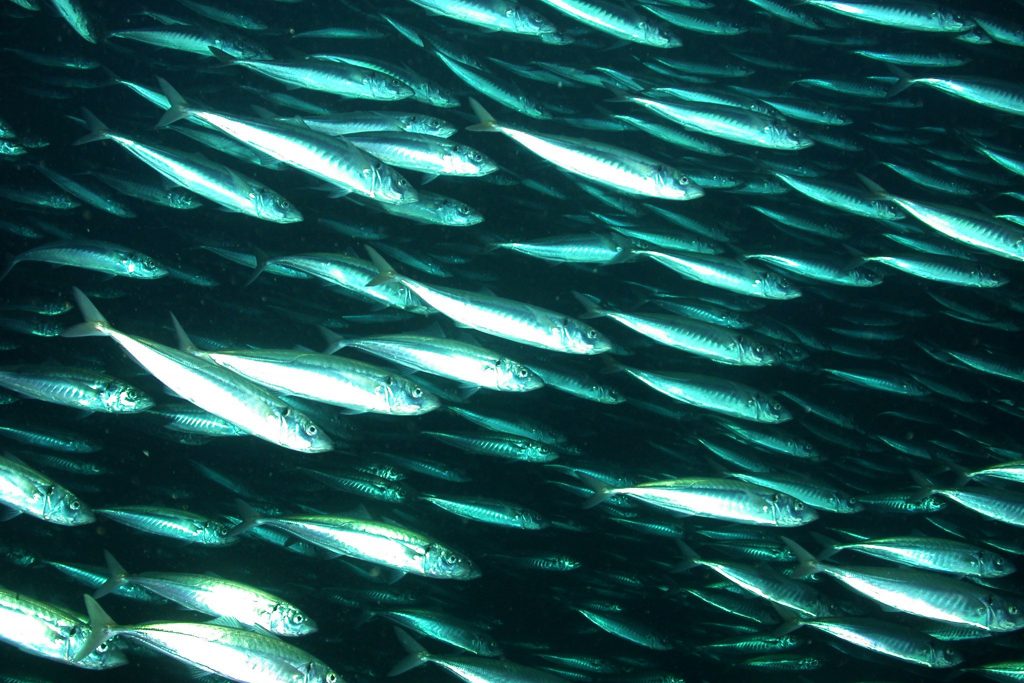

In Sea-Wind’s “Seine Haul” chapter, Carson directly addresses how humans interfere in the lives of sea creatures by describing a failed seine fishing operation. There are two primary types of seine fishing: purse seining and Danish seining. Purse seining uses a purse seine net that closes from the bottom, while the conical-shaped Danish seine net herds and scoops up the fish. Despite the different mechanisms, both purse and Danish seining target schools of fish. “Seine Haul” describes how a mackerel and fishermen feel while the latter fishes for the former. The dual perspective personifies the mackerel and humanizes the fisherman. Carson describes the stress felt by a particular mackerel, Scomber, as he is caught in the grips of the net. From the perspective of the fisherman, Carson writes: “He suddenly wished he could be down there, a hundred feet down, on the lead line of the net. What a splendid sight to see those fish streaking by at top speed in a blaze of meteoric flashes!”

The appreciation the fisherman has for the mackerel and reverence he has for the sea complicates notions about the ethics of fishing. It at once terrorizes the fish while bringing humans closer to the sea. The situation reveals the power dynamic between humans and the sea. Humans use the sea as a resource and the sea resists, evident when the mackerel escape the net. What is clear, however, is that fishing cannot be divorced from the sea ecosystem.

In detailing a tern’s relationship to the sea (a type of seabird), Carson indirectly and perfectly characterizes the human-sea relationship:

They feared to alight on the water, for although terns take their living from the sea, they are not truly of it. To them the sea was a strange element to which they must abandon themselves for a brief and frightening instant of contact as they dived for a fish, but not a place on which they would willingly reset their fragile bodies.

The sea is part of our world but also separate from us. Like the tern, we are fragile in the strong currents of the sea. We cannot live in it. Machinery (boats, diving equipment, submarines, etcetera) separates us from complete immersion. Therefore, we try to dominate the sea (through fishing, for instance) but the sea controls us.

Under the Sea-Wind captures the beauty, violence, and complexity of the sea and life connected to it. The book reveals the interconnectedness of nature, which includes humans. We are part of the never-ending drama that makes the sea a magical, mysterious, and merciless place. Through her gift as a writer and knowledge of the sea, Carson reminds us land-bound creatures—even those of us nestled in the Appalachian mountains—that our world extends beyond the land to the depths of the sea.

Annie Chester is a writer and co-founder of expatalachians. She writes about the environment and culture in Appalachia and abroad. She is currently a postgraduate student at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.