Over 150 years before J.D. Vance or the 2016 election, a novella in The Atlantic magazine focused on the plight of America’s laboring class. Published in 1861, “Life in the Iron Mills” was undeniably inspired by author Rebecca Harding Davis’ hometown of Wheeling, West Virginia.

While perhaps one of West Virginia’s most under-celebrated writers, Davis remains a pioneer of American literary realism.

The novella focuses on two immigrant laborers in an Ohio River mill town: Hugh, a Welsh ironworker and Deborah, a cotton mill girl. They live in squalor, Davis describing the rhythms of their lives as “like those of their class: incessant labor, sleeping in kennel-like rooms.” The story describes how Hugh longs for art and beauty in the world, symbolized by the sculptures he makes from heaps of iron refuse during his breaks at the mill.

Eventually, he and Deborah are charged with theft after the latter steals from the mill’s owner and gives the money to Hugh. The final pages end with Hugh’s suicide in prison and Deborah being taken in by a Quaker community in the Ohio hills.

Gritty in its detail, “Life in the Iron Mills” forces the reader to reckon with the ills of urban industry in a way similar to Upton Sinclair’s writings a half-century later. Public outrage, however, did not follow Davis’ work—the story was published the same month as the outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861. With the national focus on holding the country together, working conditions for immigrant laborers would have to wait.

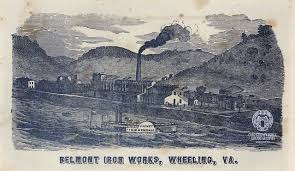

While Dickens’ London or Engel’s Manchester had covered the realities of the Industrial Age, American literature in the mid-19th century was dominated by the pastoral tales of Romanticism. Writing from her parents’ home in Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia), Rebecca Harding Davis instead found inspiration in the smoke-filled industrial center where she spent her early adulthood. Her neighborhood of Centre Wheeling was a mix of affluent row houses, such as her family’s, and the worker housing that was hastily erected within walking distance of the Belmont Iron Works a few blocks away.

While undeniably a member of the community’s educated elite, Davis was embedded with the laborers she described so vividly in in her writing.

Davis lived in Wheeling during its transformation from a rural hinterland of English-speaking agrarians to an industrial culture fueled by European immigrants. While she does not explicitly name the town on “La Belle Rivière,” her description closely matches antebellum Wheeling. A sleepy market town when she and her family arrived in 1836, by the 1860s Wheeling had become a booming industrial city and Virginia’s 3rd-largest manufacturing center. In the mid-19th century, mills were predominantly manned by immigrants from Wales, Ireland, and Germany who worked for 12 hours a day in hot and dangerous conditions. It was in this Wheeling—and Northern Appalachia—that Davis wrote.

While most of her biographers agree on her role as one of the country’s first literary realists, some, such as Tillie Olsen, also cast her as a Southern writer.

Though she did spend the first five years of her childhood in antebellum Alabama, she Davis lived the rest of her life north of the Mason-Dixon Line. She was heavily influenced by her experiences growing up in West Virginia’s northern panhandle and attending school in neighboring Washington County, Pennsylvania. To place her beside Southern writers is as off the mark as lumping her in with East Coast writers. Her early works do not jive with the dominant New England romanticists, either. In her realism and focus on the toils of the common man, she is in fact an early Appalachian writer.

Appalachian literature is often rooted in place. “Life in the Iron Mills” explicitly takes place in the Upper Ohio Valley, and many of her Civil War-era writings take place in the same western Virginia borderlands. Even her stories set elsewhere, such as Margaret Howth: A Story of To-Day (in Indiana),are influenced by her upbringing in industrial Northern Appalachia. The Wabash Valley mill town of Margaret Howth could just have easily been Pittsburgh or Wheeling.

Appalachia, especially the Northern Appalachian region, is heavily tied to working-class narratives and histories. Davis’ writings on that segment of society, and the regional focus of her early work, shows that she is solidly in the Appalachian tradition. Describing her as Southern does not quite fit her work. It’s necessary to transcend the North/ South literary divide of the 19th century to understand her.

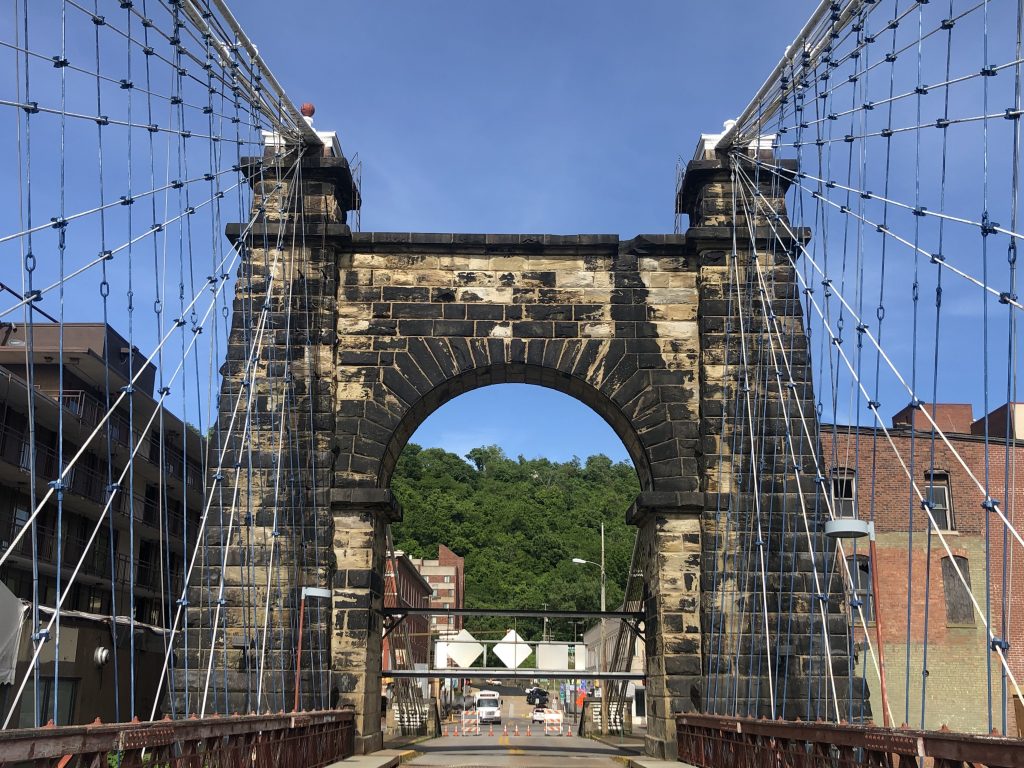

The writing of Appalachia is rarely romantic or idealistic; often, it matches the horrors of its history with parallel fiction. In “Life in the Iron Mills,” Hugh’s suffering of consumption symbolizes the pain of his existence as well as historical fact: Between 1854 and 1868, the majority of deaths in Upper Ohio Valley (aside from periodic epidemics) were from respiratory illness. Davis’ description of the “idiosyncrasy of smoke” can still be seen today in the blackened façades of Wheeling’s remaining antebellum structures.

Appalachia’s best writers must have a clear vision to understand Appalachia and what it is. Rebecca Harding Davis grasped her home and the struggles of her working-class neighbors in a way that no casual observer of Appalachia could.

While nationally important to the genesis of American Realism, she is also among the first writers from the “Trans-Allegheny” who described the land, people, and troubles of the region so accurately.

You can read the original novella in full on The Atlantic’s website.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nick Musgrave first became fascinated with West Virginia’s history while growing up in Parkersburg. He continues to read, research and write on the Mountain State’s past from its birthplace in Wheeling. For more neat history and some political snark, follow him on Twitter: @NickMusgraveWV.