Why is Appalachia poor? It’s a question almost everyone has an answer to—they just don’t always know it. Even if they’re not fully aware of it, anyone addressing Appalachia’s economic challenges has a story about why they think the region is the way it is. Maybe it’s a declining coal industry. Maybe it’s out-of-state corporate interests. Or maybe it’s just the way things have always been.

Learning how to recognize these stories is critical in addressing regional problems. After all, solving a problem is difficult if you can’t clearly talk about it. Moreover, how one answers “Why is Appalachia poor?” strongly influences how they answer other questions, like “How do we fix it?” and “Who is responsible?”

For those fighting for meaningful change in Appalachia, it can be just as important to understand how different explanations of regional poverty are used to make certain solutions seem preferable or to assign blame, as it is to get to the “right” explanation. Understanding how the stories we tell about the region drive—or impede—action can help Appalachians navigate their way to a better future.

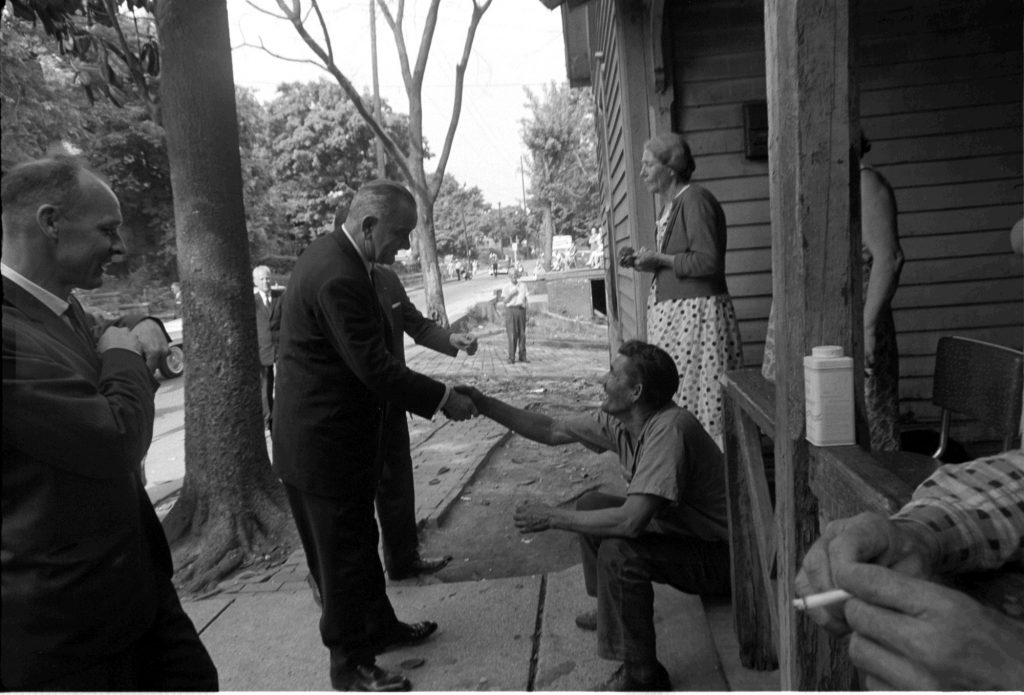

Culture of poverty

One of the oldest and most controversial explanations for Appalachia’s underdevelopment is what scholars call the “culture of poverty.” Developed in the 1960s when social scientists wanted to explain the “dysfunctional” customs of millions of Appalachian migrants flooding America’s cities, the “culture of poverty” theory holds that Appalachian culture, with its fatalistic outlook and encouragement of laziness, is ill-suited to the modern economy. Under the theory, the solution to Appalachia’s poverty is simple: “To change the mountains [is] to change the mountain personality,” as sociologist Rupert Vance put it.

The culture of poverty explanation has been widely criticized by Appalachian Studies scholars for drawing on and reinforcing stereotypes of Appalachian people as isolated, lazy hillbillies. That hasn’t kept it out of the news, though. Following the failure of the Mined Mines project, project head Amanda Laucher attributed its slow progress to “the current atmosphere in Appalachia which is deeply interested in maintaining a ‘culture.’”

In a more developed form, the culture of poverty explanation also informs J.D. Vance’s argument in Hillbilly Elegy, which he describes as a book about a “culture that increasingly encourages social decay” in the context of regional economic decline.

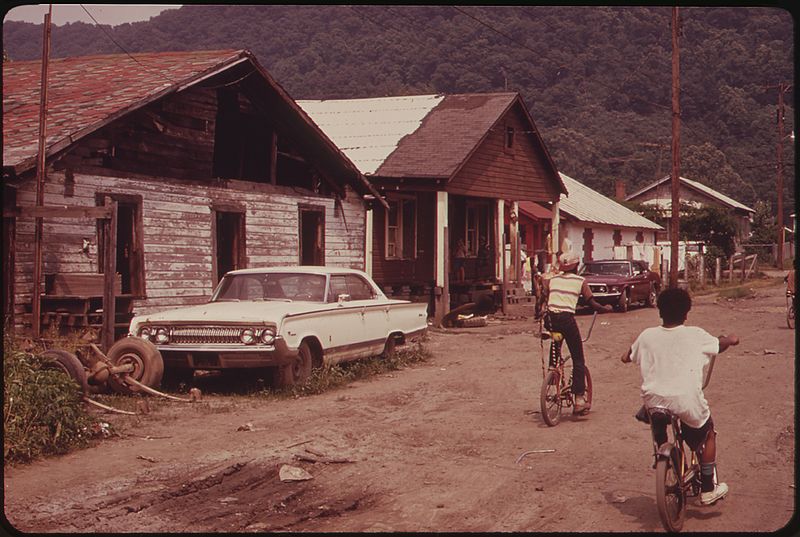

Resource Curse

Another popular explanation of Appalachian underdevelopment is what is called the “resource curse,” or the idea that places with a lot of natural resources are likely to be poorer because resource industries, like coal mining, dominate the local economy and prevent other economic sectors from growing. Under this theory, nature doomed Appalachia with abundant coal and timber resources to be a place of “rich land, poor people.”

This explanation is a large part of the story according to Adam Wells, the Director of Community and Economic Development for Appalachian Voices, a regional development non-profit. “Coal. Extractive industry was the monoeconomy…It kept more diverse opportunities outside the region,” Wells said.

In light of this apparent resource curse, folks have been calling for the diversification of Appalachia’s economy since at least the 1965 founding of the Appalachia Regional Commission (ARC). In its first report, ARC called for large-scale investment in transportation and other infrastructure to spur diverse economic development in the region. The results of this program have been mixed, with the strategy best exemplified by the Appalachian Development Highway, or “corridor,” system.

Although ARC’s top-down approach to regional change hasn’t brought about the economy it hoped for, economic diversity remains a central goal for local organizations as coal declines, with the concerted push for broadband access being a prominent example. Among other groups, Appalachian Voices supports local projects to diversify the economy, including increasing the use of solar power and promoting ecotourism in southwest Virginia.

“The keystone word is ‘diverse.’ There’s not one thing that’s gonna save us. Otherwise, we’ll be back in the same place we were before,” Wells said.

Bringing Politics Back In

Although the culture of poverty and resource curse explanations provide very different stories for why Appalachia is poor, they are similar insofar as they present Appalachia’s poverty as a straightforward, apolitical problem to be solved. As they are most often presented, both the culture of poverty and resource curse just seem to exist—natural problems of the mountains waiting to be fixed by the government, NGOs, or whoever else.

There’s little room in these theories for history, politics, or the ongoing struggles to control Appalachia’s resources. While they may be true in some sense, and can possibly help fix some of Appalachia’s problems, these stories direct attention away from the role of powerful people and groups in creating and maintaining Appalachia’s condition.

The last family of explanations, what one might call critical stories of Appalachian poverty, all seek to challenge this tendency by emphasizing the role of history, power, and inequality in determining the region’s economic trajectory.

Internal Colony

Without a doubt, the most popular of the critical theories is the internal colony model. Developed in the 1970s to provide a political explanation for Appalachia’s poverty, the internal colony model likens Appalachia’s relationship to the rest of America to that of a colony with its colonizer. Under this theory, out-of-state companies came into the region to exploit its rich natural resources, corrupted local governments to ensure their control, and left ordinary Appalachian people with little to show for it but mined out mountainsides.

In part because it taps into Appalachia’s deep history of labor conflict, the internal colony model remains a popular explanation among activists fighting against the idea that Appalachia is “naturally” poor. However, the theory has also drawn its fair share of criticism.

For one, in comparing Appalachia to historic colonies like India and many African countries, the internal colony model tends to hide the fact that the region’s European inhabitants did in fact colonize it from Native Americans. Additionally, in presenting a homogenous, victimized Appalachia, the theory can erase important differences within the region.

“The problem with the internal colony model is that it creates too stark an opposition between insiders and outsiders…Once you get an entrenched local elite, they have a very strong interest against [economic] diversification,” said Betsy Taylor, a cultural anthropologist working on Appalachian economic development and a founder of the Livelihoods Knowledge Exchange Network (LiKEN). In other words, the model can hide the role of powerful local actors like coal barons Don Blankenship and Jim Justice, and Senator Joe Manchin.

Inequality

Rather than focusing on insiders vs. outsiders, Taylor suggests a more useful and accurate explanation for Appalachia’s poverty would focus on the unequal access to wealth in the region, especially land, created by land speculation over the last century.

“Seventy to 90 percent of land in some [Appalachian] counties is still absentee or corporate land, and a lot of the coal and timber companies leased their land from these companies. Harvard University actually still has a chunk of land…It’s the connection between this land grab and local gatekeepers that’s important,” Taylor said.

In light of this fact, LiKEN, Appalachian Voices, and other groups have started investigating land ownership in the region to help map the way to a post-coal future for Appalachia. “I think having a national conversation about land ownership…and thinking about the use of public lands and public revenues is important,” Taylor said.

Whichever explanation or solution they may prefer, those working to address Appalachia’s poverty can agree that a “just transition” from coal entails rectifying the region’s historical inequalities. “It all comes down to a just transition. The people that gave the most [in the old economy] should benefit first in the new economy…Whatever shape the economy takes, we need to not make the same mistakes as before,” Wells said.

As they continue their march to a brighter future, Appalachian activists would do well to recognize the subtle yet powerful ways stories of Appalachian poverty motivate, constrain, and direct their movement.

Selected Readings

- Uneven Ground: Appalachia Since 1945

- The Road to Poverty: The Making of Wealth and Hardship in Appalachia

- Journal of Appalachian Studies – Internal Colony Issue

- Appalachian Land Ownership Survey Records, 1936-1985

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nicholas Brumfield is a native of Parkersburg, WV currently working in Arlington, VA. He is also a 2007 recipient of the West Virginia Golden Horseshoe for exceptional knowledge of West Virginia history. For more hot takes on Appalachia and Ohio politics, follow him on Twitter: @NickJBrumfield.