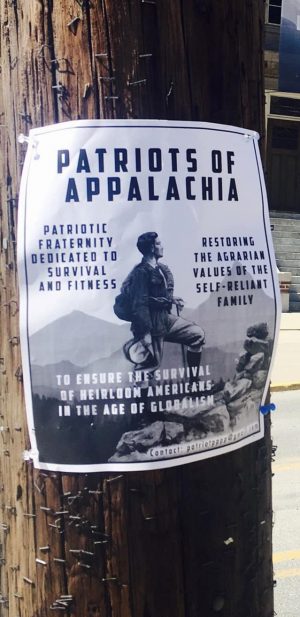

Earlier this year, a series of alt-right flyers were distributed in North-Central West Virginia. Placed by white nationalist groups such as Patriot Front and Patriots of Appalachia, the leaflets railed against “globalists,” called for the “survival of heirloom Americans” and for patriots to “reclaim your birthright.” In the wake of the Charlottesville rally last year, white nationalism—or its ability to emerge from the shadows—is on the rise around the country, and Appalachia is not spared from this phenomenon.

One of the flyers recently found in North-Central West Virginia. Via Twitter. (Note: the Patriots of Appalachia account has since been banned and/or deleted).

Though perhaps unprecedented in many of our lifetimes, this tide of American nativism is hardly the first in the region. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, immigrants shaped both urban and rural Appalachia, leaving their mark through some of our favorite foods and festivals today. As new waves of migrants arrived, the self-described “native” Americans discriminated against the most recent arrivals, with more-established immigrant communities often joining in.

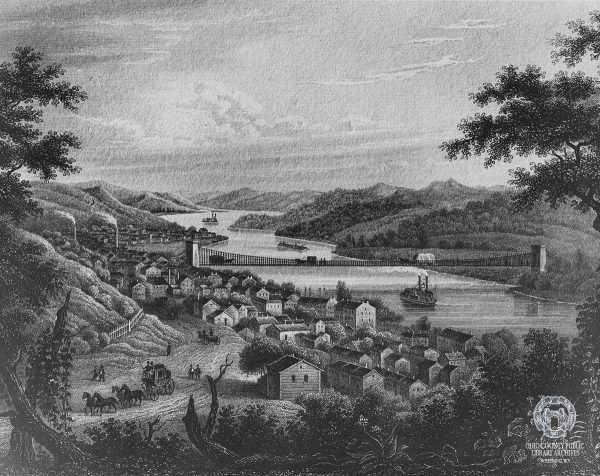

Such was the experience of the various ethnic groups who settled in the Upper Ohio Valley of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia in the mid-19th century. As cities like Wheeling and Pittsburgh became transportation and industrial hubs, foreign-born workers and their families flocked to the valley. Particularly in Wheeling, the first influx of immigrants were the Irish, who fled their native island during the Great Famine starting in 1845. In 1852, the connection of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to the city brought the laborers who had built the railroad and other migrant workers to Wheeling’s burgeoning industry.

Wheeling as it appeared in 1850. Via Ohio County Library Archives.

It was not, however, just accent and nationality that separated the Irish from the locals. Previously, the population had been overwhelmingly Protestant and native-born. Many early arrivals to Wheeling hailed from the east coast and were old-stock Yankees. The earliest city directories mention a myriad of Protestant churches but only one small, Catholic church. The flood of Irish immigrants between the 1840s and 1870s challenged this status quo. As the Irish population of the Ohio Valley grew, so too did the number of Roman Catholics. The influx of Irish Catholics was so significant that in 1850 Pope Pius IX created a new diocese based in Wheeling.

These divides—immigrant and native-born, Catholic and Protestant, laborer and tradesman—came to a head in 1854 with the arrival of a Papal Nuncio, or ambassador. Archbishop Gaetano Bendini had been sent by the Vatican on a six-month tour of the United States and arrived in Wheeling on January 4 at the invitation of the Bishop of the new Diocese of Wheeling, The Most Rev. Richard V. Whelan.

On the morning of Saturday, January 7, Wheelingites arose to find handbills posted throughout the city decrying the arrival of Bendini. According to a January 9 article in The Wheeling Intelligencer, the posted bulletins eschewed any subtlety:

Freeman, Arise! Bedini [sic], the Butcher of Italian Patriots, the Tyrant of Italy is in our city! Aye, the guest of the Catholic Bishop. He is on a mission through our Union as a kind of Papal Ambassador and should nowhere be tolerated by American Freeman, as he is not worthy to breathe the free air of this Country, yet he is feted everywhere by the Jesuits, to the great annoyance of free American citizens.

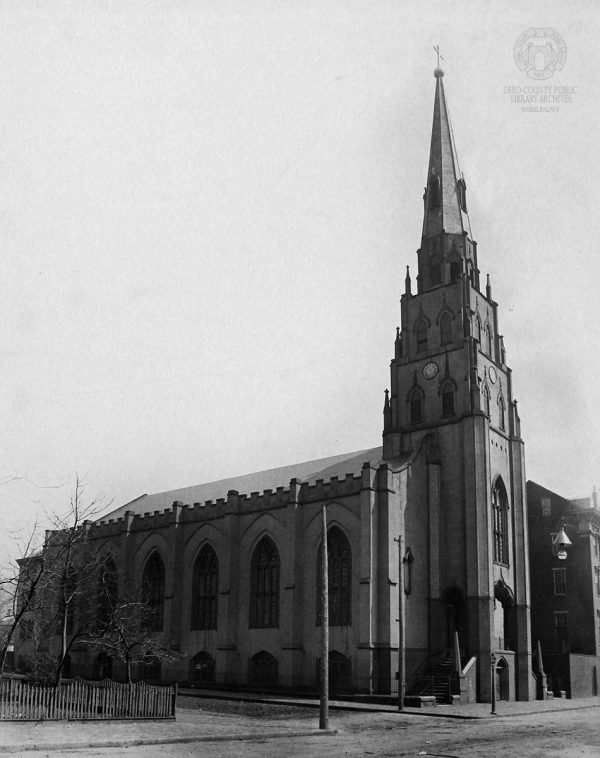

What happened on the evening of January 7 is still debated by historians. The Intelligencer reported that nativists heckled attendees at a fundraising dinner for the steeple of the new St. Joseph’s Cathedral, with the paper condemning their actions. However, testimony from Wheeling’s chief of police and other accounts allude to a much more serious incident bordering on a public riot. That would not have been without precedent, as Cincinnati had recently experienced civil unrest caused by Bendini’s visit there on Christmas. Perhaps the most popular story, especially in the valley, is that after hearing of the bulletins, Bishop Whelan called upon the Irish Catholics of Wheeling and Ritchietown (today’s proletariat South Wheeling neighborhood), who gathered arms and guarded the cathedral and bishop’s residence from a nativist mob.

Regardless of how violent the night was, what is certain is that Bendini was smuggled out of town by train on the morning of January 9. A rumor spread through town that an attack against his life had been planned at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad depot but was thwarted or simply fizzled out. Bendini safely traveled to Washington, D.C., but not before his presence caused another riot in Baltimore on January 18.

As the Irish immigrants to Wheeling—and the Ohio Valley—became more established, the discrimination and religious hatred they faced waned. By the 1870 census, Germans had eclipsed the Irish as the largest foreign-born group in Wheeling and much of the distrust of immigrants reoriented toward them. This cycle continued throughout the century; as new ethnic groups arrived in the valley, they replaced another at the bottom of the food chain. By the end of the century, men with Irish and German surnames sat in the region’s powerful industrial boardrooms, while Eastern Europeans (derogatorily called “hunkies” and “polaks”) toiled in the low-paying and dangerous mills.

This cycle continues today and is further complicated by ethnic and racial divides. While in 2018, the flyers espouse white nationalism and warn against “globalism,” they are merely 21st-century updates on a 150-year old theme: it’s “Us” against “Them.” Resistance to racism and nationalism will remain a struggle for the foreseeable future, but some solace can be found knowing that cooler heads most often prevail. The Nuncio left unharmed then, and the bulletins are being taken down now.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.