Black and carbon-rich, the sedimentary rock called coal is central to Appalachian identity. Highly combustible, coal has been used for millennia to generate energy. Nevertheless, industrial exploitation of coal is on the decline.

Now, far from the coal seams of Appalachia, a “new frontier” of mining is underway in the depths of the ocean.

Coal mining declined in Appalachia because it was not economically viable and natural gas extraction, notably fracking, was. Similarly, Deep-sea mining (DSM) offers an alternative to the frustrations of terrestrial mineral mining. Demand, trade wars, and complicated extraction and separation methods associated with terrestrial mineral mining are driving countries and contractors to the deep sea. There, they can mine the rare-earth minerals that are needed to build today’s modern electronics.

Operating machinery at watery depths beyond 660 feet (200 meters) poses engineering challenges and high costs. This, coupled with the fact that no one owns the “Area”—the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction”—creates barriers to commercial DSM operations. Thus, DSM exists in an exploratory phase, controlled by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an autonomous governing body created by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS).

The coal mined in Appalachia belonged to the state and individual property owners before companies acquired mineral rights. Federal and state regulations were later created to protect public health and the environment, yet there is a well-documented history of coal companies endangering workers and violating regulations.

According to CDC data, from 1839–2010 there were 726 documented mining disasters, many a result of coal companies blatantly violating safety regulations. One example is the 2010 Upper Big Branch mine disaster. Then-CEO Don Blankenship of Massey Energy, the company responsible for the event, “was convicted in 2015 on a misdemeanor count of conspiring to violate federal mine-safety laws.” Similarly, companies in West Virginia intentionally abused compliance schedules to violate discharge limits of selenium, a pollutant that “causes reproductive impairment and birth defects in aquatic species.” The list of coal company violations goes on.

DSM is not coal mining, yet coal mining should serve as a cautionary tale. Regulations, as coal mining illuminates, do not guarantee environmental and public health. Appalachians should watch DSM closely because we know the pain and trauma that mining can cause. Although terrestrial mining is different from oceanic mining, the environmental damage caused by both is devastating. Like the mountaintops of West Virginia, once deep-sea hydrothermal vents are mined, they are destroyed.

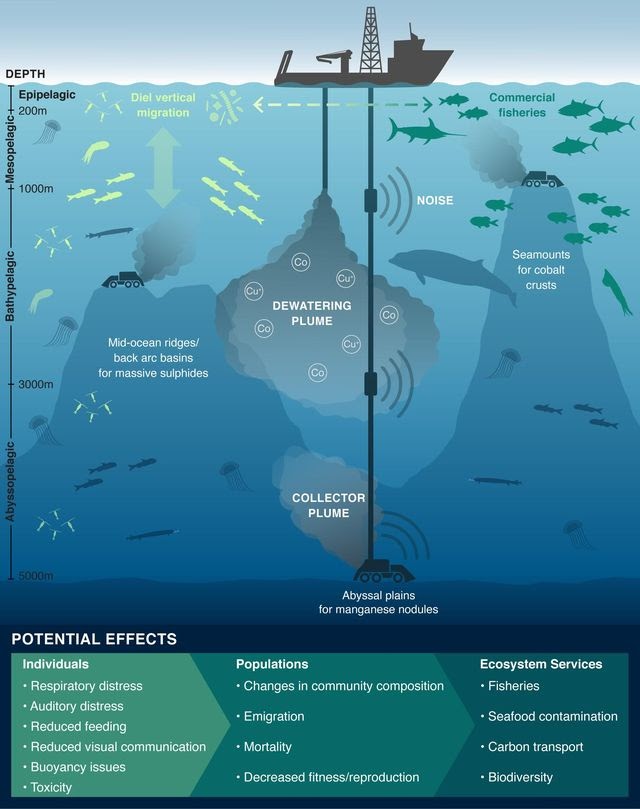

Hydrothermal vents, chimney-like structures where seawater meets magma, are involved in polymetallic sulphide mining. Polymetallic sulphides, along with cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts and polymetallic nodules, are the mineral deposits harvested with DSM. Polymetallic nodules, nodules for short, garner the most attention. They are potato-shaped deposits containing manganese, nickel, copper, cobalt, molybdenum, and other rare-earth metals. Nodules “cover vast areas of the ocean floor,” particularly in the area known as the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone (CCZ), which stretches from the west coast of Mexico to Hawaii. In addition to their relative abundance, nodules are also easier to mine.

DSM operates under the assumption that exploitation is inevitable to power the modern world. The possibility for recycling, circular economies, more sustainable industrial practices, and innovations in technology and social organization are widely ignored by DSM research. The insistence for commercial DSM will come at a cost: DSM will leave a wave of devastation in its path to obtain minerals.

Biodiversity will certainly suffer, and not just at the lowest depths where mining occurs. Sediment plumes and noise, traveling through the water column, will disrupt ecological systems in the deep midwaters; an ecosystem that represents “more than 90% of the biosphere.”

It is astounding to realize the vastness of the ocean. We humans are made of water, yet detached from the ocean. We cannot survive the pressure of the depths below. The deepest that divers—French professionals armed with specialized gear— have descended without a capsule is 1,752 feet (534 meters). Even in specialized submersibles, our eyesight fails us in the black depths of the abyssal zone, 9,800 feet (3,000 meters) down.

Though misguided, it is easy to view the deep sea as nothingness because we cannot see or experience it. Science, however, has shown that the deep sea is integral to total planetary health. From nutrient regeneration, which supports fisheries, to absorbing carbon dioxide, which slows anthropogenic global warming, the deep sea provides vital ecosystem services. Our physical, human limitations should not obscure this fact.

Appalachia, far from the sea in the embrace of the mountains, is yet connected to the deep sea. As described above, the deep sea provides services that benefit the entire planet, even Appalachia. The history of coal mining connects Appalachia to the deep sea in an even more profound way. Although the governing structures of DSM vary considerably from coal mining, this does not negate the fact that the deep sea is threatened by the prospect of mining.

This year, the first “comprehensive set of rules, regulations and procedures” will be issued by ISA “to regulate prospecting, exploration and exploitation of marine minerals in the international seabed Area.”

With a keen understanding of how regulations can cause harm, Appalachians can empathize with the ocean ecosystem and, hopefully, advocate for better protections as DSM evolves.

Annie Chester is a writer and co-founder of expatalachians. She writes about the environment and culture in Appalachia and abroad. She is currently a postgraduate student about to submit her master’s dissertation on deep-sea mining and governance. This article was inspired by that research.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.