Turn on the news any day, and you’ll likely see stories about the increasing effects of climate change. Unprecedented wildfires in California, sea level rise in Florida, even the subway flooding in New York. While the severity and timing of its effects remain debated, the national conversation around climate change has morphed over the past decade. It’s no longer a question of if we can stop it, but of how we’re going to cope with it.

As with many national conversations, Appalachia may end up central to the American strategy to cope with climate change, and not necessarily for the usual reasons. With the ongoing decline of Appalachian coal, old debates about balancing the region’s carbon-based economy with environmental concerns have become less prominent.

Instead, Appalachia’s importance in the coming decades may be based on another of the region’s valuable resources—habitable land—and its ability to serve as a refuge to those displaced by climate change. Navigating the possibilities and pitfalls of this growing importance will be key in ensuring a just future in the region.

According to most experts, climate change’s effects will be increasingly felt throughout the United States over the next century, although as Eric Engle, chairman of the Mid-Ohio Valley Climate Action group explains it, different regions of the country will face different challenges.

“The Western United States, the Southwest are seeing huge problems with record-breaking heat, drought, and wildfires. You’re seeing the threat of hurricanes and extreme weather events [along the Gulf, Southeast, and Northeast coasts]. In the Midwest and Mid-Atlantics states… you’re seeing intervals of drought and extreme precipitation events that destroy crops,” Engle said. “We’re already seeing these things…but by mid-to-late century, they’re going to get worse.”

Like most everywhere, Appalachia will not be spared the effects of climate change. Cities in southern Appalachia are some of the most drought-vulnerable in the country, while the region’s Ohio River Valley is particularly vulnerable to increased flooding, a fact underlined by the deadly 2016 floods in West Virginia.

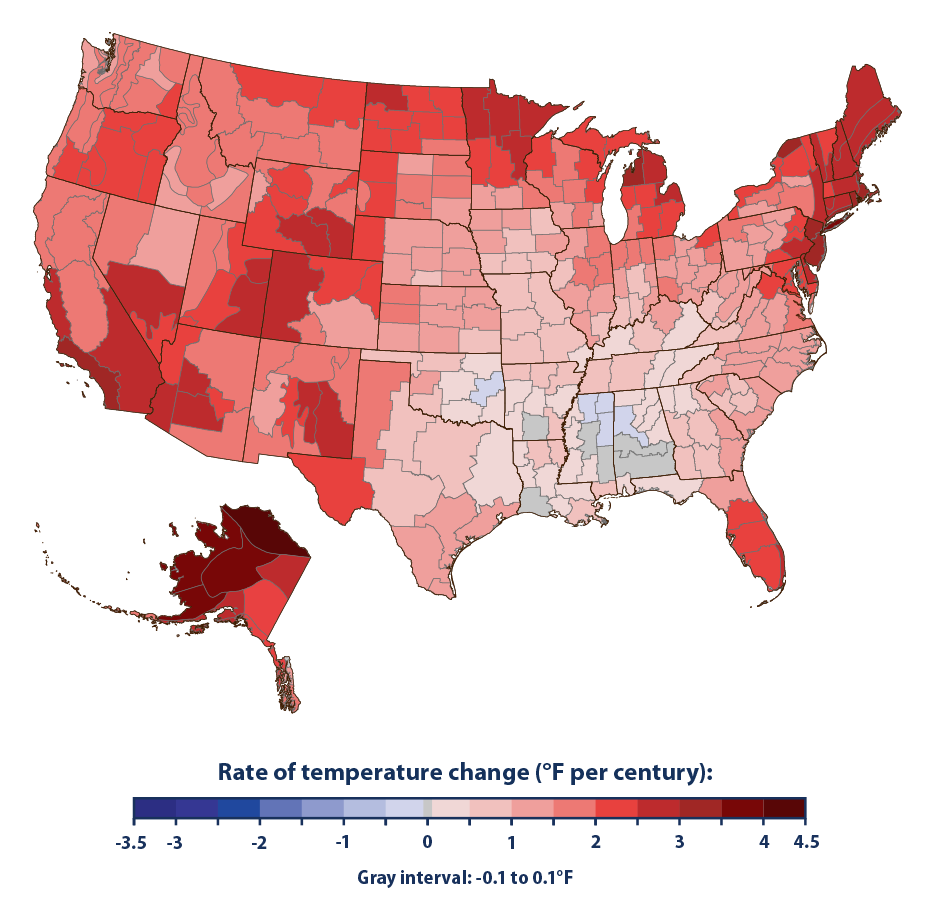

However, as a whole, the Appalachian Mountains appear better positioned than most areas to weather climate change, with the environmentalist group Nature Conservancy predicting Appalachia’s hardy ecosystem could help preserve plant and animal species displaced by changing climatic conditions, a role it played during the last Ice Age. And although it’s important not to get complacent, the region comes out relatively well in projections of climate change’s effects on temperatures, crop yields, and even GDP growth.

“I would caution this being a region that would be mostly exempted from climatic changes. Now, by comparison…relative to other places in the United States and on the North American continent, we may do well here. We may be more habitable than other areas of the country or the continent,” Engle said.

While the popular image of the ocean rising to the Appalachian foothills is fortunately not predicted, experts predict Appalachia will be a relatively hospitable place to live in the coming century. This of course raises the question: What does that mean for Appalachia and the people who live there now?

Although the thought of Appalachia serving as a redoubt against climate instability may provide a measure of comfort, some Appalachians have already raised concerns about how coming changes may marginalize the region’s already-vulnerable population.

“In the coming decades…we may see people saying we want to get back to states [like West Virginia] because there are future prospects. Maybe employment isn’t the best, but the housing is cheap. The land is comparatively cheap,” Engle said. “I worry about that because I don’t think it’s fair to current central Appalachians. Those of us who are here and suffering…I worry that we’re failing to take care of people who were born and raised here.”

The concern over ‘“outsiders” coming in to gentrify Appalachia and displace local inhabitants has a long history, which in turn draws on an even deeper history of the region being exploited by out-of-state interests.

And these concerns are valid. Local governments in Appalachia have recently launched several initiatives to entice out-of-state professionals to settle in the region, even as local media has reported on how out-of-state buyers interested in living in a climate change resilient location have helped put a squeeze on the West Virginia housing market.

However, if Appalachia’s losing battle against coal’s decline has taught us anything, it should be that swimming against the currents of the world economy is often a losing proposition. Rather than reactively trying to prevent any newcomers, regional activists and policymakers should actively promote an inclusive economic vision harnessing the opportunity more people may bring to the region.

What that vision should include, exactly, is up for debate.

For Engle, a major part of it must focus on reversing the long-term exploitation of Appalachia and its most vulnerable. “West Virginia’s history in particular has been a history of exploitation by out-of-state interests and people. That has to stop. What we create here…a large portion of that needs to stay and what does not stay here still needs to reward people here,” Engle said. “We deserve the wealth of our labor…If we want to make this equitable, to encourage people to stay and come here. We have got to be willing to take care of our most vulnerable populations.”

If Appalachia’s long-term trajectory is to be changed, any inclusive vision for the region’s potential future as a climate change haven must also include a fundamental reckoning with its deeply unequal land ownership. Although not talked about as much as the dependence on coal, land inequality has been central to Appalachia’s poverty for over a century, with large out-of-state companies buying and holding land as an investment.

Betsy Taylor, a cultural anthropologist and founder of the Livelihoods Knowledge Exchange Network (LiKEN), explained how land ownership was crucial to Appalachia’s economic trajectory in a 2019 interview with expatalachians. “A lot of the coal and timber companies leased their land from these companies. Harvard University actually still has a chunk of land…It’s the connection between this land grab and local gatekeepers that’s important [in explaining Appalachia’s poverty],” Taylor said.

This inequality is still very much present in the region.

In a 2013 study, the West Virginia Center for Budget and Policy found the top 25 landowners in West Virginia—most of which were out-of-state energy, landholding, and timber interests—owned over 17 percent of the state’s 13 million privately-held acres. In six counties in the state’s southern coalfields, the top ten landowners held over 50 percent of the land.

If there ever is a climate change land rush in Appalachia, those interests will be the primary beneficiaries. They will profit from rising land prices while ordinary Appalachians are priced out of the market. They will benefit by catering to the affluent while threatening to destroy the very ecosystems that make Appalachia resilient to climate change. The story of exploitation with which the region is so familiar will be repeated.

“I’m afraid we’re going to get back into old ways of thinking,” Engle said. “Places like West Virginia are going to be exploited from the outside…and we’re gonna continue on the same long-term trajectory we’ve been on since we were created as a state during the Civil War where certain people eat all the pie and everybody else gets crumbs if they’re lucky.”

As frightening as a climate changed future may be, one can imagine a scenario where it is able to provide the much-needed ingredients of people and capital to finally change Appalachia’s century-long trajectory, to create a more prosperous society. However, if ordinary Appalachians are to have any chance of getting more than crumbs in this new society, they must force a reevaluation of the fundamental ways wealth is distributed in the mountains.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nicholas Brumfield is a native of Parkersburg, WV currently working in Washington, DC. For more hot takes on Appalachia, the Middle East, and socialist Tanzania, follow him on Twitter: @NickJBrumfield