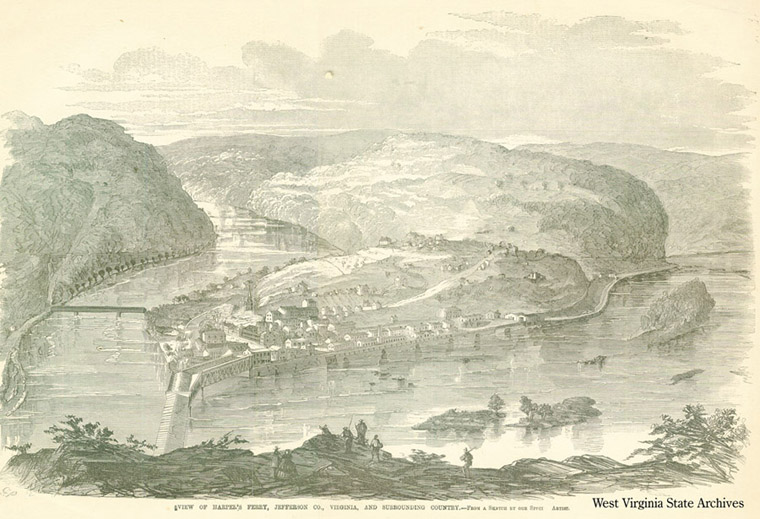

Harpers Ferry is one of the most idyllic towns in West Virginia. Nestled on a narrow peninsula between the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers, it is steeped in history and natural beauty and is a popular tourist destination. Contributing to both of those is St. Peter’s Catholic Church. The building is perched on a steep hillside at the edge of the “Lower Town,” prominently towering over the National Park below. It is also, conspicuously, the only church remaining in the original part of Harpers Ferry, all others being destroyed or damaged during the Civil War.

While it never became a large city, the area was one of the first in Appalachia to industrialize in the early 19th century. George Washington himself saw the rivers’ potential as a power supply and lobbied for the United States Armory and Arsenal to be built at the site. The first muskets were produced in 1801 and continued to be made and stored in Harpers Ferry until the Civil War.

In addition to the Federal arsenal, which stretched along the Potomac, private industry soon followed on Virginius Island in the Shenandoah. A variety of water-powered mills, a machine shop, and an iron foundry were all established there. These manufacturing endeavors all required manpower, and an influx of migrants from the East made their way to Harpers Ferry.

While most of the region’s early settlers were Protestant and typically Scots-Irish, these new industrial workers included some Irish Catholics. Their spiritual needs were first met by priests traveling from Pennsylvania and Maryland until 1825, when the first parish in that part of Virginia was established in Martinsburg.

The slow trickle of Irish immigrants exploded in the 1830s when both the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and Baltimore and Ohio Railroad reached Harpers Ferry. Construction of these projects was especially arduous and relied on the labor of recent immigrants desperate for any work. The Diocese of Richmond quickly responded by establishing a new parish in Harpers Ferry in 1830. The construction of St. Peter’s Church began the same year and was completed in 1833.

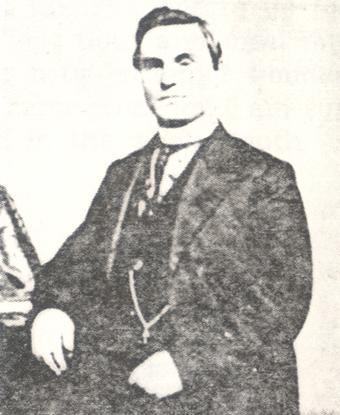

The parish remained small by coastal standards, but it was still one of the first three to be consecrated in Trans-Allegheny Virginia. The parish welcomed its first resident pastor, Rev. Richard V. Whelan, in 1834. From his base at St. Peter’s, Rev. Whelan traveled as previous area priests had done, shepherding the small but growing Catholic communities in the northern Shenandoah Valley. He served as pastor until 1841 when he was appointed the second Bishop of Richmond, which at the time covered all of Virginia. In 1850 he was named the first Bishop of Wheeling, the new Diocese established to serve all of modern-day West Virginia except for the eight counties of the Eastern Panhandle, which were added in 1974 to create the current Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston.

The early Catholic Church in West Virginia, like most of the United States, was heavily dominated by the Irish. Whelan was born in Baltimore of Irish immigrant parents, and while less is known of the priests of St. Peter’s in the 1840s and 1850s, their surnames of O’Brien, Plunket, and Kenny point to Irish Catholic roots.

In 1857 St. Peter’s Church welcomed a new priest directly from Ireland. Rev. Michael A. Costello was born in Galway and received his theological training at All Hallows College in Dublin, which trained priests to serve abroad. Costello immediately traveled to the United States after graduating and reported to the Diocese of Richmond, which named him the pastor of St. Peter’s on November 5.

While previous priests watched as the town and its industries grew, Costello would bear witness as it all came crashing down. The importance of Harpers Ferry as a supply line and railroad town made it a key strategic target during the Civil War, despite the intentional burning of the Armory and Arsenal by retreating Federal troops in the opening weeks of the war.

Situated along major transportation routes, Harpers Ferry was caught in the ebb and flow of moving armies throughout the conflict. The town changed hands at least eight times, sometimes through bloodless retreats but also as a result of sieges and pitched battles. The largest was in 1862, when Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson surrounded the town and captured over 12,000 Union soldiers after two days of fighting and artillery shelling. By the end of the war, nearly all industrial buildings and all but one of the churches had been destroyed or severely damaged. The sole exception was St Peter’s Catholic Church.

The survival of the physical and spiritual parish was not by accident. While many of the town’s clergy fled with the bulk of the civilian populace early in the war, Father Costello remained in Harpers Ferry to watch over his church and the remaining members of his congregation. He continued to hold mass and administer the sacraments, which often included last rites to soldiers dying of battlefield wounds or disease. But his presence in the town was not what saved St. Peter’s—it was his cleverness that likely preserved the building.

As an Irishman, Costello was well aware of the pointed neutrality of the British government and the Confederate hopes that the British would support them. Sources note that Costello erected a flagpole atop the church’s steeple and flew the Union Jack in an effort to protect the building. While not definitive, a hazy image from July of 1863 during the Gettysburg Campaign—which skirted the area around Harpers Ferry—shows an indistinguishable flag atop an untouched St. Peter’s spire.

Costello died of illness at 34 in 1867. He was replaced by Reverend John Joseph Kain, himself a native of the area. His parents immigrated from County Cork and his father worked as a laborer on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which caused the family to follow the route as the tracks pushed further west. Kain was born in a railroad camp outside of Martinsburg in 1841, and was baptised there by none other than Richard Whelan, who would give mass at the railroad and canal camps while pastor of St. Peter’s.

Rev. Kain’s first assignment brought him home to West Virginia to serve as pastor at Harpers Ferry in 1867. In addition to ministering to the congregation there, he was also responsible for the surrounding churches which were administered as missions of St. Peter’s. Many of those had been severely damaged during the war, such as those in Winchester and Berkeley Springs. He continued to rebuild the foundations of faith in the northern Shenandoah Valley until 1875 when he succeeded Whelan in becoming not only the second Bishop of Wheeling, but the second priest of St. Peter’s to elevate to the ecclesiastic rank.

Though the physical and spiritual Catholic Church in the region was gradually rebuilt following the Civil War, the town of Harpers Ferry was not.

The destruction of the Armory and Arsenal ensured that the already obsolete manufactory was never rebuilt. Some private industry resumed in new forms, but floods in the second half of the century halted further development and led to the closure of the last remaining commercial enterprise along the Shenandoah, a pulp mill, in 1893. The town’s population was cut nearly in half during the 1860s and never recovered. From an 1850 peak of 1,747 residents, it never held more than 1,000 residents following the war. Today, fewer than 300 remain.

St. Peter’s Church was substantially renovated in the 1890s, giving it the Romanesque style seen today. The town held onto its parish until 1999 when the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston merged it with the parish of St. James in nearby Charles Town, which itself had begun as a mission of St. Peter’s. The church was not abandoned or deconsecrated, and remains an active chapel of St. James’ Parish, with masses offered each Sunday for a mix of locals and tourists.

A small church in a small town, St. Peter’s Catholic Church had an outsized influence on the early church in West Virginia. Not only was it one of the first parishes in the boundaries of the current diocese, it also produced the first two Bishops of Wheeling. That influence was undoubtedly Irish in nature, as was the church, an attribute that very well may have spared the building from destruction during the Civil War.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nick Musgrave first became fascinated with West Virginia’s history while growing up in Parkersburg. He continues to read, research and write on the Mountain State’s past from its birthplace in Wheeling. For more neat history and some political snark, follow him on Twitter: @NickMusgraveWV.