Nestled between France and Italy, the island of Corsica has a distinct culture influenced by a tumultuous history and mountainous geography. The Genoese ruled the island from the 1500s until 1729 when the French took over. Agriculture is difficult on the mountainous island, but the pleasant Mediterranean climate aids in the growth of many delicious crops including grapes, clementines, and chestnuts.

Of all the foods grown in Corsica, none is more culturally significant than the chestnut. Corsica is not unique in its deep connection to chestnuts. Around the world—from Italy to China and Appalachia—chestnuts played an important role in society.

The omnipresence of chestnuts in Corsica is thanks to the Genoese, who during their rule mandated that landowners and farmers grow chestnut trees. This mandate mitigated the threat from famine, which plagued the island. Soon, the chestnut proved to be a reliable and hearty food source. Pascal Paoli, a Corsican resistance leader, famously stated, “Tant que nous aurons des châtaignes, nous aurons du pain”—“As long as we shall have chestnuts, we shall have bread.” The consumption of chestnuts reaches its height in Corsica during Christmas time. The harvest begins in autumn—as early as September—and ends around November. By Christmas, chestnuts are transformed into products ready for the holidays.

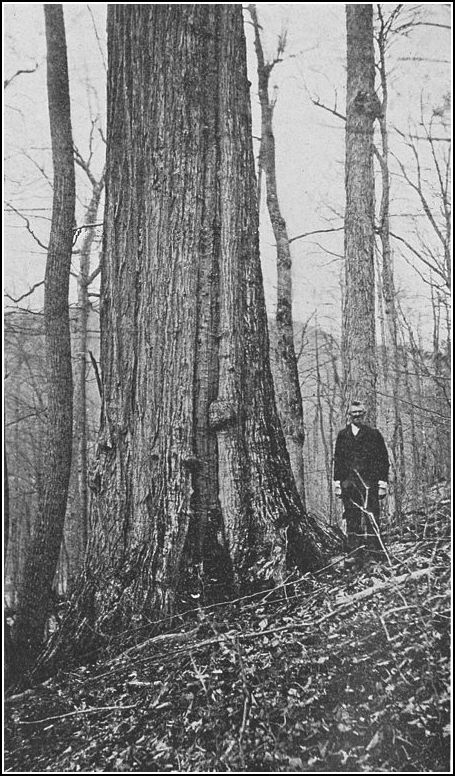

Like Corsica, the Appalachian mountains create agricultural challenges, especially in more remote parts of the region. Historically, chestnut trees–specifically the American chestnut species–grew abundantly throughout Appalachia, about four billion trees strong at their height. With the same growing season as trees in Corsica, the consumption of chestnuts in Appalachia also coincided with the Christmas season. Likewise, chestnuts were the bread of Appalachia, supplying mountain folk with a reliable food source. It was a common practice, as it is in Corsica, to let pigs grow fat foraging for chestnuts.

But tragically, unlike the rich chestnut culture and economy that thrives in Corsica today, Appalachia lost this significant cultural and economic resource.

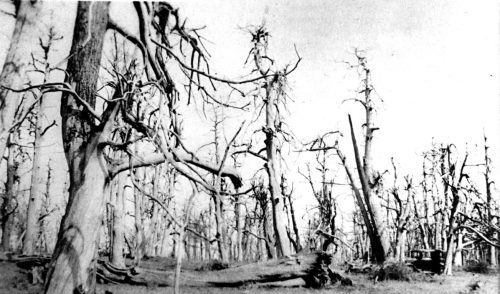

The demise of the American chestnut happened only a few generations ago. Its fall started when a non-native fungus that originated in Asia afflicted trees at the Bronx Zoo with blight (disease) in the 1900s. It quickly spread, killing nearly all American chestnut trees by the 1950s—which comprised 25 percent of the forest canopy in their growing range at the time.

The American chestnut produced a smaller and sweeter nut compared to Chinese or European variations, and the desire for a larger nut drove imports of the Asian chestnut in the 1900s. As Mark Double, an American chestnut researcher at West Virginia University, said, “The size of its nuts led to its demise.”

“My dad and his cousin filled a Model-T full of chestnuts and drove to Washington D.C. where they sold the chestnuts along with some moonshine,” said Rex Mann, a retired forester and self-proclaimed “chestnut evangelist” of The American Chestnut Foundation’s Kentucky chapter. They did this during the Great Depression era around Christmas time.

Like Mann’s father, Double recalled the stories his father and grandfather told him about the glory of the American chestnut. His father couldn’t afford shoes growing up, so “He and his siblings collected chestnuts to earn money for shoes.” Double’s grandfather, who grew up in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, told Double that in the 1910s, “mountains around Uniontown would be white in June because so many chestnut flowers were blooming.”

Further emphasizing the tragedy the blight caused, Turner Sharp resident of West Virginia and member of the Eastern Native Tree Society wrote:

It is hard for the residents of now to understand how the demise of the American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) impoverished the citizens of the Eastern United States and especially residents of Appalachian areas. The Chestnut had many uses. Lumber for homes, furniture, barns, fencing, nuts for human and livestock consumption, bark extract for tanning leather. It was an important part of wildlife habitat and food.

Luckily, hope remains for the American chestnut. Although functionally extinct under USDA standards, the American chestnut survived because the disease did not kill the tree’s root system. This allowed scientists to begin restoration efforts that continue today.

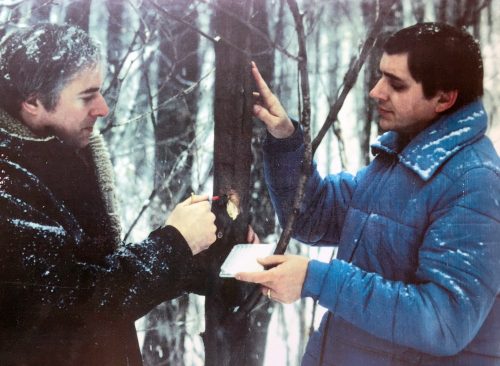

The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) is the primary group in the United States supporting restoration efforts. TACF has 16 chapters nationwide, representing the historic range of the tree from Maine to Georgia. Alongside the efforts of TACF, institutions like West Virginia University and the State University of New York of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF) conduct research and support restoration efforts. Currently, there are three different restoration approaches: cross-breeding, transgenics, and hypovirulent inoculation.

After forming in 1983, TACF focused on cross-breeding American with the blight-resistant Asian chestnut trees. “This is the primary effort in West Virginia, but each state chapter is different in restoration efforts,” Double said, who is also president of TACF’s West Virginia chapter.

For example, the New York chapter supports transgenic (altering the genetic material of an organism by adding the genetic material of another organism) research at SUNY-ESF. Dr. William Powell, SUNY-ESF professor and Co-Director of the American Chestnut Research and Restoration Project, is part of ESF’s research team. They use genetic engineering to move a gene from wheat into the American chestnut. Because of this new gene, the tree can detoxify oxalic acid, the weapon the fungus uses to kill the trees.

“No single gene [in the Asian chestnut] will give you full resistance, which makes breeding difficult,” Powell said. He also worries that cross-breeding will produce a tree that is too short because American chestnuts, unlike the Asian trees, are canopy trees. To fix this, Powell said they’ll use all the tools at their disposal, transgenics and breeding, “to produce blight-tolerant trees that can adapt to their native range.”

The other restoration method, hypovirulent inoculation, uses a form of the fungus that contains a virus. This virus, called a hypovirus, grows slower and allows the tree time to wall off the fungus, thus reducing its impact of the blight.

The method developed after scientists observed European chestnuts survive the blight thanks to this hypovirus. Since its discovery, North American scientists have worked to inoculate American chestnut trees with the protective hypovirus. However, “there is an extremely diverse population of fungus in the United States,” Double lamented.

This fungal diversity makes it hard to inoculate North American trees because the hypovirus does not protect all trees from all types of fungus. Work is in progress to create a “super donor fungus,” but research is ongoing. “Hypovirulence might be a way to save individual trees,” Powell said, but because of the complexities of inoculation, it is not the best method for a large restoration effort.

Beyond protecting regional biodiversity, restoration has the potential to revive the lost culture of chestnuts. “Mountain people would gather chestnuts from the forest by the wagonful,” Mann said. “They would sell the chestnuts which were then transported by train to major cities like Pittsburgh to be sold in stores or on the street.”

The economic importance and culinary use of chestnuts prevail in Corsica, where a yearly chestnut festival gathers crowds and chestnut products–from beer to jam to the raw nuts–are sold in grocery stores. Chestnuts can also be found roasting on an open fire at Christmas markets and in popular Christmas delicacies like chestnut-flour cake. Maybe one day chestnuts will be restored to their former glory in Appalachia. In the meantime, Appalachians can reminisce about their lost history by looking to Corsica.

Questions, concerns, or thoughts about this article or chestnuts in Appalachia and Corsica? Email Annie at annie@expatalachians.com.

Annie Chester is a writer and co-founder of expatalachians. She is currently an English teacher on the Island of Corsica, France.