All cultures have developed crafts, making a useful item into art that shows off something about the culture’s values. Many sorts of crafts were seen as “women’s work” to be done in the house or in communal women’s spaces. Crafts are also a way to relieve stress or tamper anxiety. In Appalachia, women are leading figures in a movement to keep those crafting and art traditions alive. Women in Asheville, North Carolina and Parkersburg, West Virginia, for example, are at the center of movements to revitalize crafting for individual and community good.

Women’s leading role in crafts is a global phenomenon. In Morocco, women weave sturdy and beautiful rugs, often in women’s-only spaces and cooperatives. In Ireland, wool sweaters with traditional patterns differentiate family identity and protect family members from the cold. In Appalachia, before Western armies and domination by settler populations, women’s crafts were central to daily life among native peoples like the Cherokee. Appalachia is home to many Native American tribes with variations of traditional crafts and art which still thrive today with some groups—like the Cherokee in western North Carolina.

In the 19th century, commonly referred to as the “Victorian era,” male-dominated crafts like blacksmithing and furniture were seen as inappropriate for women. Strict family roles, based on patriarchal structures reinforced by churches and male-dominated governments at the time, and limitations on women’s rights meant women were often relegated to domestic-focused creations like quilts and embroidery. Those tasks were seen as less remarkable, less valued. Nevertheless, women continued to create and, eventually through organizing, opened markets to women-led crafts. Production moved out of the home and into places of business. Appalachia was home to much of that Victorian era stigma, though women on the frontier in Appalachia worked hard in the fields and at home, unlike their wealthy counterparts in European and American cities, gender roles remained much the same as in the rest of America.

Perhaps the most well-known women’s craft of Appalachia is the colorful quilts that have been passed down for generations or displayed in heritage museums. Quilts were practical–they kept the family warm in tough winters—but they were also a way for women to express themselves, their culture, and their love.

Quilts weren’t simply a practical necessity, though. They have a history of subversion and dissent against the status quo, such as patriarchy and racism. During slavery, quilts featuring a North Star were sometimes used as symbols of a friendly house on the Underground Railroad. Many of these “Craftivists” were women forgotten in history, resisting through crafty gestures and subtle signs. Craftivists are “not only reclaiming gendered activities out of choice, but engaging with an already-political practice of everyday resistance through-making,” said Caroline Chapain, a lecturer at the University of Birmingham in England.

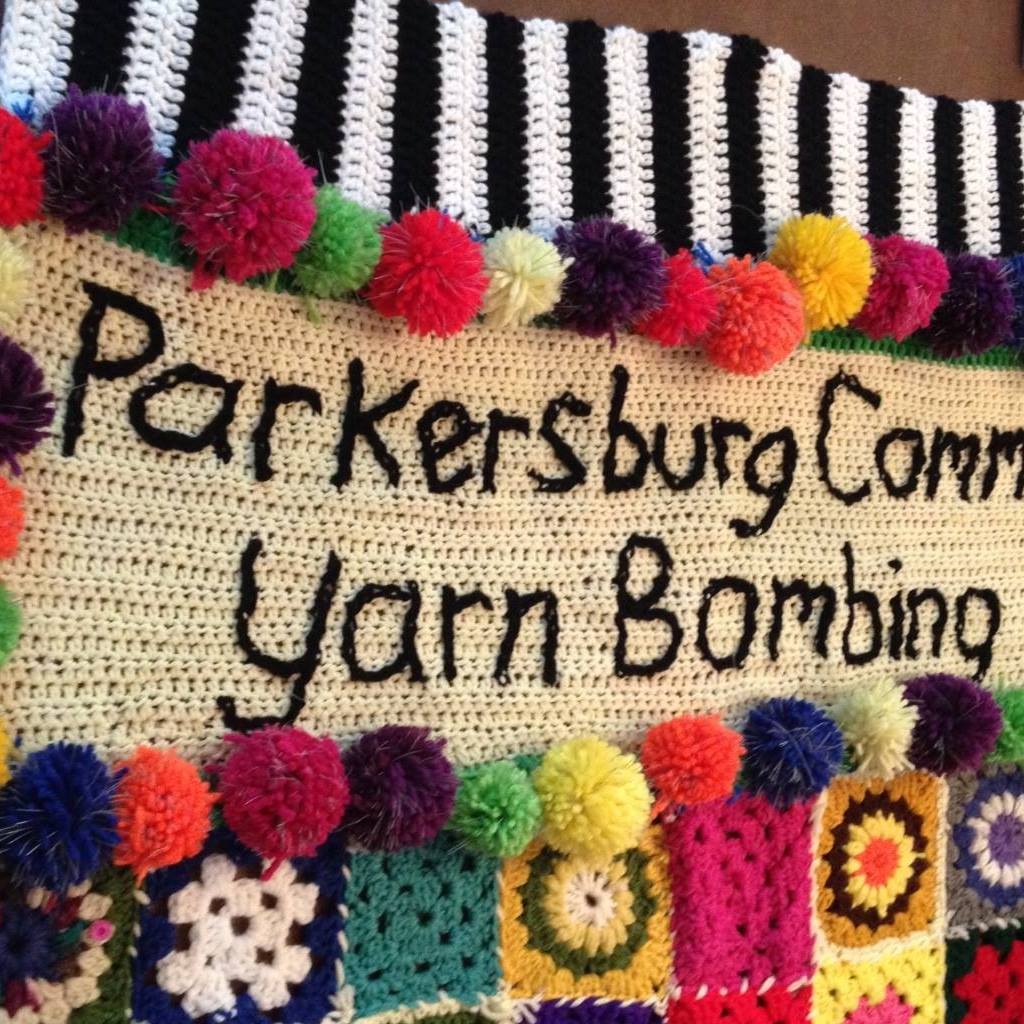

Subversive crafting has become popular among activist and women-led groups. One form of this is through knitting or crocheting a street art, a practice known as “yarn bombing.” During my time at Ohio University, a subversive crafting group formed where women met together to knit political statements and yarn bomb places on campus for causes such as sexual assault awareness and violence against minorities. In Parkersburg, West Virginia, a few years later, yarn bombing exploded in popularity.

Parkersburg Community Yarn Bombers display knitted and crocheted creations around their city to beautify the area and celebrate diversity. The group was formed by two local women, Kim van Rijn and Rina Goins. The group put up displays in over 70 locations including: 56 public community areas, like parks and lamp posts, and 14 private homes around the town. This year they will be holding major displays at the libraries and continue to invite community volunteers to join the efforts.

In Asheville, North Carolina, a women’s-only craft space called Purple Crayon is gaining popularity. Similar to a shared workspace, Purple Crayon hosts workshops, offers space at communal tables, and reserves stations for dedicated crafters. Pam Robbins started the company in October 2017 because she felt “there wasn’t any place like this for women, who aren’t professional artists, to come in community and create together,” she said.

The space is open to any women-identifying folks who want to create. Most of the women, including Robbins, are not professional artists and craft as a hobby. Robbins’ business model keeps pricing accessible for all. She wanted an all-women’s space to cultivate a welcoming environment where women feel “comfortable coming as they are. They don’t have to dress up or put on any makeup” and their work isn’t judged, she said.

The space cultivates living traditions by fusing old and new ways to create all sorts of crafts and art: quilling, quilting, collaging, and more. The crafters take the essence of old art forms and often create something new. The crafters also offer workshops to teach members of the community craft traditions.

Crafty groups or businesses, like Parkersburg Yarn Bombing and the Purple Crayon, represent women’s leadership and innovation in their communities. They are also creating new traditions along the way. The stories behind these women’s reasons for starting crafting are varied; business opportunity, community development, feminism, and more. The crafts created by women can be message-driven, diverse. On the other hand, many of these craftivists are simply doing what they enjoy. The subtlety of crafts as self-expression gives many women a space to breathe from everyday pressures or be powerful on their own terms that will transform along with society.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Alena Klimas is a writer and cofounder of expatalachians. She also manages the weekly newsletter, The Patch. Klimas recently moved to Asheville, NC to work on regional development projects with a small consulting firm. She enjoys the vibrant outdoors and beer culture in her new home.

****Correction: The original article noted Parkersburg Community Yarn Bombing “put up displays in over 56 public community areas, like parks and lamp posts, and 70 private homes around the town. ” After talking with co-director Rina Goins, the information was updated to “The group put up displays in over 70 locations including: 56 public community areas, like parks and lamp posts, and 14 private homes around the town.”