Three years ago, I sent in my application to the Peace Corps. I applied for a youth development position in Morocco due to my background studying Arabic. In September 2017, I boarded a plane with a commitment to two years of service and no idea what might lie ahead. After nearly three months near Meknes for training (between the capital city of Rabat and Fes in northern Morocco), I was placed in Ait Bougamez, the valley where I would live for two years.

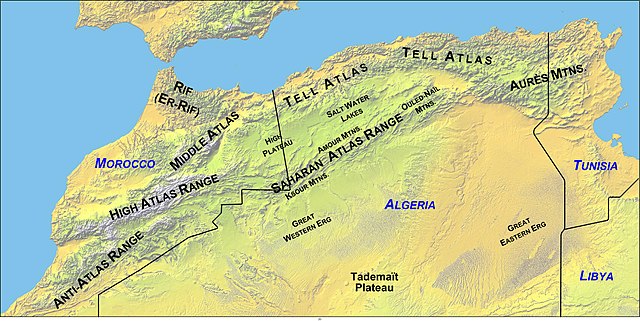

Ait Bougamez, nicknamed Happy Valley, is a remote string of about 25 villages in the center of the High Atlas Mountains, over 7,000 feet above sea level. It is two hours by car to the nearest provincial capital city (Azilal) and five hours to a major city (Marrakech). Most people make a living in apple and walnut farming, although a few work in local schools and post offices. Most people own donkeys, not cars.

I spent two years learning and listening (or trying to with my limited language skills) about the history and experiences of the people in the mountains. I saw how hard the women worked, the way people valued community, and the hopes young people had for the future. I also saw the struggles of an unstable economy, the negative views toward inefficient government, and rigid gender roles.

People in the village would often say, “You wouldn’t understand, everything is great in America.” The alluring idea of the American dream and the shallow portrayals of American life in Hollywood films penetrated even the rural village I lived in. Many people in other parts of the world are unaware of the diversity in America, the economic hardships some people face, and even the existence of rural America.

In many ways, locals were right in assessing my privilege in holding a US passport, being white, and growing up in a more-developed country. On the other hand, I often found myself relating to the struggles of the villagers.

Close friends were surprised when I explained that America was more than just New York or Los Angeles, that it also had lush, green mountains, and that my father owned a flock of chickens and lived in the woods in Preston County, WV. In discussing my own experiences with poverty and rural life, I tried to communicate how America is more complicated than it may appear from the outside.

Of course, there are important differences. Different histories, languages, religions, and more. However, while it is important to keep these in mind, I also think it can be useful to see how experiences in the High Atlas and Appalachia overlap.

First, this is somewhat an apples-to-oranges comparison. Many factors differentiate the regions: dominant religions, languages, colonial history, water supply, and governments, to name a few. But after living for two years in a remote village in the High Atlas Mountains among Amazigh people, I find it more useful to see how similar the two areas are.

To be clear: the Amazigh people are not Arabs. Often called Berbers (a name many consider derogatory), Amazigh refers to the family of languages and ethnic groups indigenous to North Africa before the Arabs arrived in the region with the rise of Islam. The Amazigh of the High Atlas Mountains are mountaineers through and through, with a long history of resistance to outsiders and colonial forces.

When Arab Muslim dynasties arrived in Morocco in the 8th and 9th centuries, the Amazigh fought them. Dihya, a warrior queen, remains a popular folktale in the area. Even after the Muslim conquests, local empires ruled from world-famous cities like Fez and Marrakesh could rarely penetrate into the mountains. The Bougamez Valley, nestled in the towering ridges of the High Atlas, has only recently come under tighter government control, along with a small influx of the Arabic language. Even today, Arabic is rarely heard when walking around the villages—the common tongue is the Tamazight language.

That the word Amazigh roughly translates to “free man” always seemed vaguely familiar to the way West Virginians tout “montani semper liberi,” the state’s motto: “mountaineers are always free.”

Another thread of defiance connecting the Atlas with Appalachia was labor action. While serving in the schools of Ait Bougamez, the assignment turned out to be quite turbulent due to massive Moroccan teacher strikes that hit especially hard in rural areas, lasting months. The students struggled to pass exams and were hurt by the strikes. It was an interesting crossover to see teachers striking at home in West Virginia at the same time. Over the past few years, West Virginia teachers have flexed their own labor rights—first in 2018 over raises and pensions, and again earlier this year over the Omnibus bill.

Another shared rural challenge is economic development. Ait Bougamez is a rural valley and the residents who live there are proud of their mountain home. However, they also can’t find many jobs to support them and their families in the valley. Most young students pursuing higher education must travel at least four hours to attend college, and a degree doesn’t guarantee a job, especially in rural Morocco.

Many young women looking for marriage prospects try to find a man living in nearby cities, perhaps due to economic mobility or because city life is much easier than rural life. Most rural women in the High Atlas work the fields, take care of farm animals, and tend to housework like cooking and cleaning (tasks that are not to be undervalued in this setting). Not to mention, the brutal cold of the High Atlas mountains.This trend of women’s agricultural work is not unique to Morocco, but rather a larger trend in Africa.

And I found this issue of rural depopulation at home as well. With the exception of Monongalia County, the population in West Virginia is in decline. Especially in my hometown of Parkersburg, quite a few public schools—such as Worthington and McKinley—are closing down due to low enrollment. Though much like in Morocco, there is a hopeful sentiment surrounding “Homecomers.”

Even though the area is extremely rural and remote, most of the valley has 4G networks. I often saw people riding on donkeys checking their Facebooks via smartphones. On a backpacking trip deep into High Atlas canyons, I told everyone I would be offline and unavailable for the week. However, that night and every night at camp I was surprised to still be “on the grid.” Morocco is one of the most advanced in telecommunications in Africa, mostly due to the Maroc Digital 2020 strategy.

When my family visited, they joked that I had better coverage in rural Morocco than my father’s house in rural West Virginia. West Virginia still struggles with broadband and phone service: In April, Facebook announced its investment in a 275-mile cable to drastically increase internet coverage. Other Appalachian states also face challenges in connecting rural areas, such as Kentucky’s “1.5 Billion Dollar Information Highway to Nowhere”.

The issues listed above are just a few striking examples that I often thought about during my Peace Corps service. I still wonder: Are these challenges innate to rural places? To mountains? During my service, I spent a lot of time reflecting on similarities and differences between the Amazigh culture of Ait Bougamez and my own experiences in West Virginia. The majority of the time, I found more things in common.

Coming home, I expect a lot of questions about my experience living in a Muslim-dominated country. While Islam plays a major role in daily life in Morocco, the country and my experience therein cannot be reduced to this one facet. Instead, I hope to bring nuance and much more of a shared experience to fellow Americans.

This experience in the Atlas Mountains humbled and changed me in more ways than I can count. I learned from strong Moroccan mommas and friends about community and hard work. I wondered along trails and trade routes that people have walked for hundreds of years. Often my heart ached for home but I found solace under the apple trees or on the trails which reminded me of places in Appalachia. It’s inevitable, now that I’m home, I’ve left a piece of me there in the small village and I carry some of the Atlas mountains culture with me.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Alena Klimas is a writer and cofounder of expatalachians. Klimas is passionate about economic and community development in Appalachia. Now, she’s living in Asheville, NC working on rural community development. To learn more about the expatalachians team, click here.