A coal baron hasn’t paid more than $2 million in taxes to his eastern Kentucky county. A West Virginia governor uses his political office for private profit. And an Ohio “economic development” office wants to grow Ohio’s economy but ignores southeast Ohio—the poorest part of the state.

Whether it is tax evasion, the unethical use of a politician’s power while in office, or corporate welfare, the public foots the bill. They pay more in taxes or service fees but get fewer services at a lower quality. Grifters and well-connected businessmen, though, laugh their way to the bank.

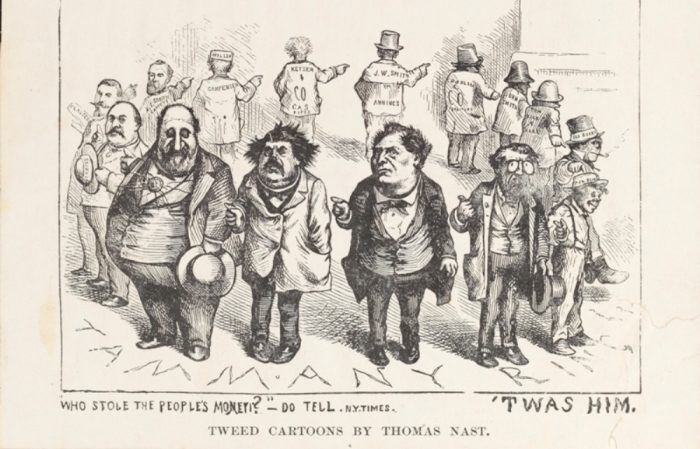

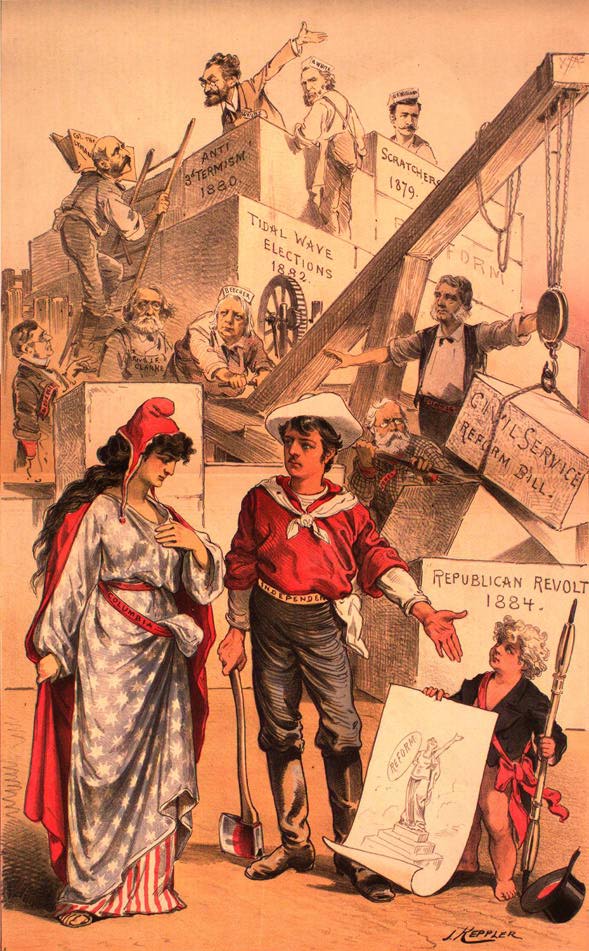

It’s not a new phenomenon. The muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens noted that “the spirit of graft and of lawlessness is the American spirit” when he wrote The Shame of the Cities in 1904. Graft, when politicians use their political power for personal gain, hasn’t gone away.

But the fleecing of the public, especially in rural areas, is a growing problem. Local, state, and federal governments keep getting bigger. At the same time, local newspapers disappear or downsize, which means that city councils and state offices have fewer people watching what they do.

What was once the responsibility of large, profitable local papers now falls on citizens, be they journalists writing for a niche online publication (hello from expatalachians!) or locals with a bone to pick.

With that in mind, the public needs to know what graft looks like—and how to follow it.

Tax Breaks

Tax breaks offer businesses lower taxes for a certain period of time (or no taxes at all) to spur local growth. Ohio, for example, abated almost $249 million in taxes across the state in 2018. That money would have gone to funds for road repairs, schools, health departments, and everything else in the state budget. Instead, the state must do without it—or raise taxes on citizens and businesses who don’t have a lobbyist in the statehouse.

Tax breaks are used across the country—and often. In 2017, Brooke County, West Virginia approved a tax break to a power plant that meant $230,000 in lost revenue annually for its school system. The tax break lasts for 30 years, according to the Wheeling Intelligencer. Though the plant is supposed to make yearly contributions to the Brooke County Commission and the Board of Education, it’s much less than what the tax revenues would have been without the tax break.

And in November 2017, Brooke County had to consolidate its primary schools to avoid running a deficit, going from seven schools to four.

Defenders of tax breaks claim that they are necessary to attract and retain businesses. If the county or state can offer $2 million to a company that will create $20 million in economic growth, isn’t the long-term growth worth a short-term sacrifice?

The problem is that tax breaks rarely bring in new companies. Economist Tim Bartik has studied these business development incentives and found that they only work, at best, about 25 percent of the time. The other 75 percent of the time, a firm decides what to do regardless of the government’s incentive.

Corporate Welfare

Tax breaks, which can be relatively small or claimed by many companies, have become more common in recent decades. They’re less noticeable because they’re spread out over more companies and harder to track than direct cash subsidies. But corporate welfare in the form of megadeals, which give a package of tax breaks, money, and resources to one company, still happen (such as the circus that was Amazon’s search for its second headquarters).

In 2012, for instance, West Virginia gave $98 million to Gestamp, a Spanish engineering company, to locate an auto parts stamping plant in South Charleston. In 2004, North Carolina sent $279 million to Dell for a computer manufacturing plant in Winston-Salem. And in Pennsylvania in 2012, then-governor Tom Corbett pushed through a $1.7 billion deal to attract an ethane refinery (known as a “cracker” facility) built by Royal Dutch Shell to Beaver County, for fear that Shell would otherwise build in Ohio or West Virginia.

All of those deals were passionately defended by the politicians and companies who expected to benefit from them. The overall effect of deals like those made in West Virginia, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania, however, is a waste of taxpayer money and a breach of the public trust. The Dell plant, for example, closed after four years. Politicians generally don’t know enough about the future to make wise economic decisions. Nor do they have the right to gamble with public money. When they do, schools lose funding. Local taxpayers are forced to “invest” in a private company. And competing businesses work in an unfair economy that encourages them to play politics instead of serving customers.

Corruption

The “development incentives” listed above are a relatively refined form of modern-day graft. Old-fashioned corruption, however, such as what Lincoln Steffens chronicled more than a century ago, remains alive and well.

In August, a federal judge in Buncombe County, North Carolina issued prison sentences for five county officials. They were involved in “horrific abuse of office” and “out-of-control criminal activity,” including bribery and the misuse of public funds, according to the Asheville Citizen-Times. County Manager Wanda Greene, once praised as the best county manager in the country, will spend seven years in prison.

Yet, while Greene enriched herself until a federal investigation caught up to her, West Virginia Governor Jim Justice remains in office. The ironically named Justice, according to Forbes, has personal or company tax liens, fines, late bills, and liabilities for mine reclamation that amount to almost $100 million by a conservative estimate—or up to $300 million. One of Justice’s coal companies has flaunted orders from the state of Kentucky to halt coal extraction. Back taxes and government fines haunt him as well.

In April, the Justice Department launched an investigation into Justice’s possible conflict of interest from his ownership of the Greenbrier Hotel, which has received state payments. An August report from the Charleston Gazette-Mail and Propublica cataloged more of his conflicts of interest. And, in October, the Associated Press discovered that a farm owned by Justice’s family is the biggest recipient of soybean subsidies in West Virginia, hitting the maximum limit of $125,000.

Without reporting from local outlets like the Charleston Gazette-Mail, Asheville Citizen-Times, and Lexington Herald-Leader, it’d be much harder to track corruption or know how much money governments give to businesses. Some watchdogs have emerged, such as Good Jobs First, which has detailed databases to track tax breaks, subsidies, and corporate misconduct. And Southerly takes a regional approach to covering environmental issues in Appalachia and the South.

But as fewer journalists report on government, local citizens need to pay attention and ask questions. Attending city council meetings and keeping a skeptical attitude when public officials brag about their success in attracting businesses are good first steps. Nonprofits such as the National Freedom of Information Coalition can help anyone file a public records request to see what local governments are up to.

“Transparency is the cornerstone of reform,” Greg LeRoy, president of Good Jobs First, said at a recent conference this writer attended. Transparency is urgently needed: The costs for “economic incentive” plans have been creeping up, as the Brookings Institution noted in a 2018 study. One estimate for “export-based industries” found that local and state incentives cost $45 billion annually, which is three times higher since 1990. And The New York Times estimated that cities, counties, and states gave out about $80 billion in incentives in 2012. It’s hard to know exactly how much money governments are throwing around. The relevant information to track, calculate, and compare these giveaways isn’t easy to get.

“We are a free and sovereign people, we govern ourselves and the government is ours,” Lincoln Steffens wrote in his introduction to The Shame of the Cities. “But that is the point. We are responsible, not our leaders, since we follow them.” To remain a free people, Americans need to take seriously the corrupting unity of businessmen and politicians. It is a fundamental responsibility of citizenship to rigorously watch—and criticize—what it is that governments do.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Anthony Hennen is a co-founder of expatalachians and managing editor at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal in Raleigh, North Carolina.