If any one place can claim to be the birthplace of the progressive movement in Appalachia, it’s the Highlander Folk School in east Tennessee. Taking on the issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality, the Highlander School was formative for many American activists such as Rosa Parks and Merlin Bishop. Nearly 87 years ago, the project began simply as a space for finding community and justice.

The Founding of Highlander

In 1932, Myles Horton, Don West, and Jim Dombrowski founded the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee as a center for education and labor organizing. Myles Horton, often credited as the founder, was born in 1905 in Savannah, Tennessee to lower-class parents who were involved in labor struggles against mainly mining companies. He worked and received his education while being involved in labor struggles. In 1920, Horton traveled to Denmark to observe that country’s famous folk schools, which combined practical skills training with a curriculum focused on community, tolerance, and global awareness. A few years after returning home, Horton partnered with West and Dombrowski to create Highlander.

Highlander’s first major projects focused on literacy and labor. Adult literacy classes were key to building a foundation of education at the school to improve the low literacy rates of white and black locals in the early 1900s. Highlander was also home to the Congress of Industrial Organizations’ union workshops. One of the hallmarks of Highlander’s approach was to ensure union workshops and literacy classes were always mixed gender and race. For some, this was the first time being in a mixed-gender space, and it was one of the only places in the South for mixed race socializing.

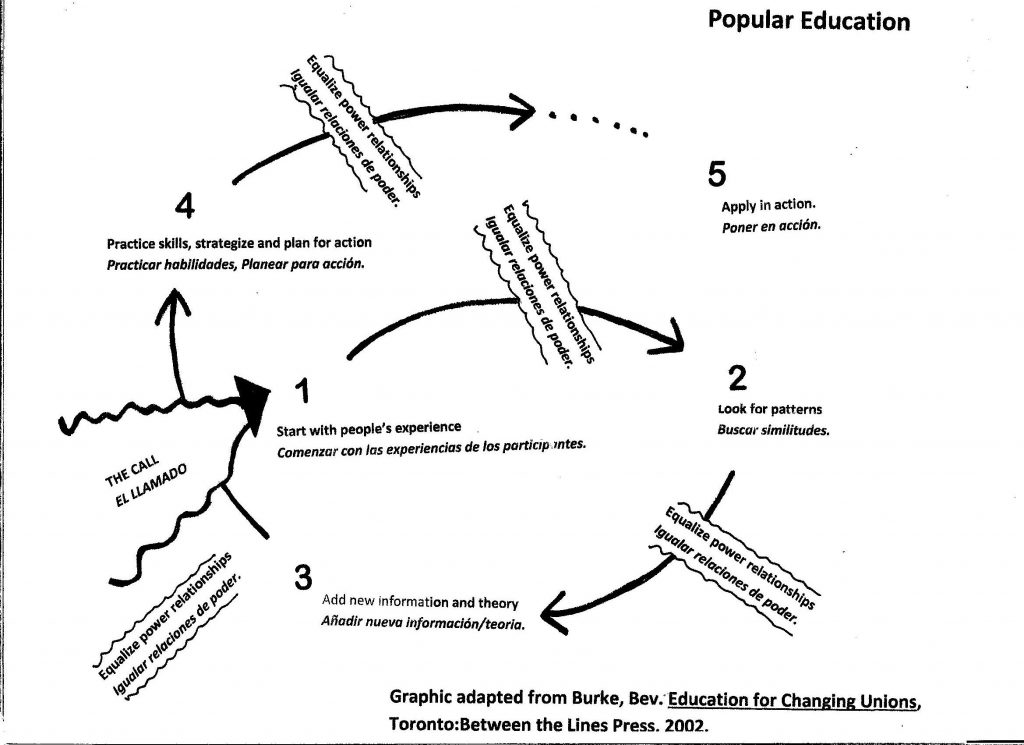

The school’s pedagogy was revolutionary. It was based on a popular education model rather than the traditional banking education model. The banking model relies on a teacher and student relationship in which a teacher possesses all information and gives it to the student. But popular education breaks down the power relationship and creates a space where all are learners, bringing people together to face the challenges of illiteracy, racism, sexism, and economic exploitation.

Not limited to Appalachia, Myles Horton’s educational system had a global presence. Horton met Paulo Freire and discussed ideology and education. Freire was an activist and postcolonial theorist from Brazil whose work was influential across South America. The two revolutionaries wrote a book, “We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change.”

The school’s reputation quickly grew in the region, although it was for the greater good—or ill—depending on who one spoke to. To its opponents, Highlander was producing “troublemakers” who were dissatisfied with their daily reality. But to its supporters, the school gave its students the tools to create social change, be it on the front lines of labor actions or segregation protests.

Race and Civil Rights

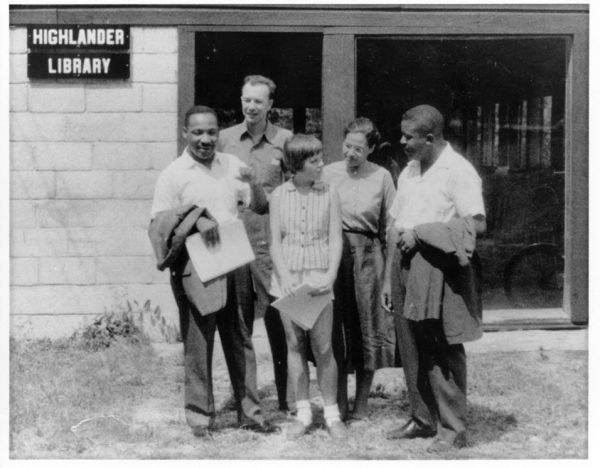

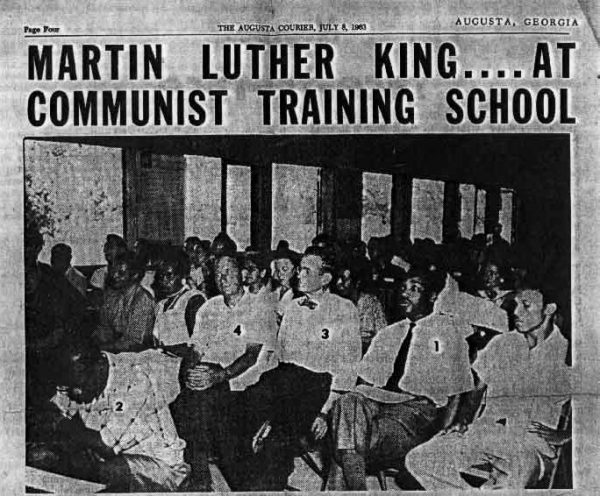

In the early 1950s, Highlander began to actively engage with the Civil Rights Movement. The school invited leaders to develop ideas surrounding activism. Through the school program, activists and community leaders gathered together to tackle segregation and racism in the United States. Some of its notable students included Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Ralph Abernathy, and John Lewis. The school’s reputation as a leftist organizing center even followed its students. In 1956, Martin Luther King Jr. was accused of attending a “communist training school” after news got out of his involvement with Highlander.

Septima Clark was the Director of Workshops at Highlander during those Civil Rights gatherings. After her time with Highlander, Clark would found a series of “Citizenship Schools” that focused on helping black Americans pass literacy tests for voting in the Deep South. These programs were a major part of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference program in the 1950s. Clark was a remarkable force who taught, organized, and left her mark at the school.

Its famous leaders were not its only memorable mark on this time period, however. Highlander stood out in many ways. Its activism and fondness for developing a culture pulled people together. In this way, the school famously drew on folk music to mobilize for social change. Artists and activists gathered at the school and came up with melodies that are still played at protests across America.

Notably, the song “Little Light of Mine” was popularized and produced during a training when Rosa Parks, Pete Seeger, and Martin Luther King Jr. gathered to share ideas. This song has become a gospel song in churches across the South. It is sung for hope in the face of darkness. From Occupy Wall Street, anti-NATO protests, and church choirs, this song has taken on more meaning and power than many realize.

“Which Side Are You On?” by Pete Seeger

Pushback

Due to its success in training social activists, the school began to experience threats and attacks from Southern politicians who opposed civil rights. This opposition culminated in the Tennessee state government revoking the school’s charter and confiscating its property in 1961. At this time, the school changed its name and moved to Kentucky.

From company bosses threatening the property to present-day political leaders calling for its removal from history books, the school weathered it all. Highlander survived the years of McCarthyism and the Red Scare while carrying a communist reputation.

Training the Youth of Tomorrow

As the Civil Rights Movement faded into the tumult of the 1970s, Highlander moved to tackle different issues in Appalachia, such as economic and environmental problems. In 1972, the center moved back to Tennessee, this time to New Market, where it remains today. The school also changed its name from the Highlander Folk School to the Highlander Research and Education Center.

Although best known for its civil rights work, Highlander continues its mission to provide popular, empowering education to all Appalachians. In a 2017 interview Highlander educator Susan Williams described the school’s curriculum by saying “popular education and organizing are actually one process: people coming together, trying to figure out what to do about a problem, learning more, talking about it, taking action, and then reflecting and trying to figure out what to do again.”

Many of the recent programs at Highlander focus on youth leadership training. In the Seeds of Fire program, for example, young people spend a year developing professional skills and learn about the political processes that will enable them to become future leaders. Similarly, the Stay Together Appalachian Youth (STAY) Project focuses on creating inclusive communities in Appalachia that will help young people stay and make a difference. STAY’s vision states, “We envision an economically and environmentally sustainable Central Appalachia where young people have the power to build and participate in diverse, inclusive, and healthy communities.”

The Highlander Education and Research Center continues to respond to political issues while staying true to its critical pedagogical foundations. In addition to youth programs, there are many fellowships, workshops, and events regularly held at Highlander. Over and over, the school has proven its ability to make change in the region.

“It remains alive because it remains real.”

Join our conversation: If you have any memories of the school or hearing about it, please comment/share and add your voice to the story.

To discover more about their current projects, visit their website and consider donating to the organization.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Alena Klimas is a writer and cofounder of expatalachians. Klimas is passionate about community and economic development in West Virginia.