October 8, 2008 was a seismic date in Appalachia. On that day, the region grew by almost 5,000 square miles. Of course, no major tectonic activity was reported and no mountains erupted out of the ground. Rather, it was on that day Senate Bill 496 became law, expanding the federally organized Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) by 13 counties, including the decidedly non-mountainous counties of Ashtabula, Trumbull, and Mahoning (Youngstown) in northeast Ohio.

Few watching the expansion considered it noteworthy. As Youngstown Congressman Tim Ryan told MetroMonthly in 2007, his city’s inclusion in Appalachia was more a question of money than geography. “It is a designation that makes us eligible for certain federal grants out of the Appalachian Regional Commission’s Area Development Program and Highway Program,” he said.

Tom Finnerty, then-associate director of Youngstown State’s Center for Urban and Regional Studies, expressed a similarly utilitarian perspective. “We qualified because of our high level of poverty, not because we’re at the Appalachian region by any means,” he said.

Anybody looking to draw a bold line around the region could look at these facts and disqualify northeast Ohio from being “Appalachian.” And in one sense, they’d be right. Of the many “objective” maps people have tried to draw of Appalachia, few include counties north of the Mason-Dixon line or the Ohio River.

On the other hand, such claims ignore both how the definition of Appalachia has changed over time and northeast Ohio’s deep connections to the region. While the policymakers behind the 2008 expansion may have thought little of it, like the slow geologic forces that built the mountains over millions of years, their seemingly insignificant decision may have cascading effects.

For much of U.S. history, northeast Ohio could legitimately claim to have the “best location in the nation.” Located at the narrowest point between the Great Lakes and the Ohio River, the area’s position helped it become America’s beating industrial heart during the 19th and early 20th centuries. As recounted in Bruce Springsteen’s song “Youngstown,” northeast Ohio’s location between Minnesota’s “Mesabi Iron Range” and the “coal mines of Appalachia” helped it become the center of the U.S. steel industry.

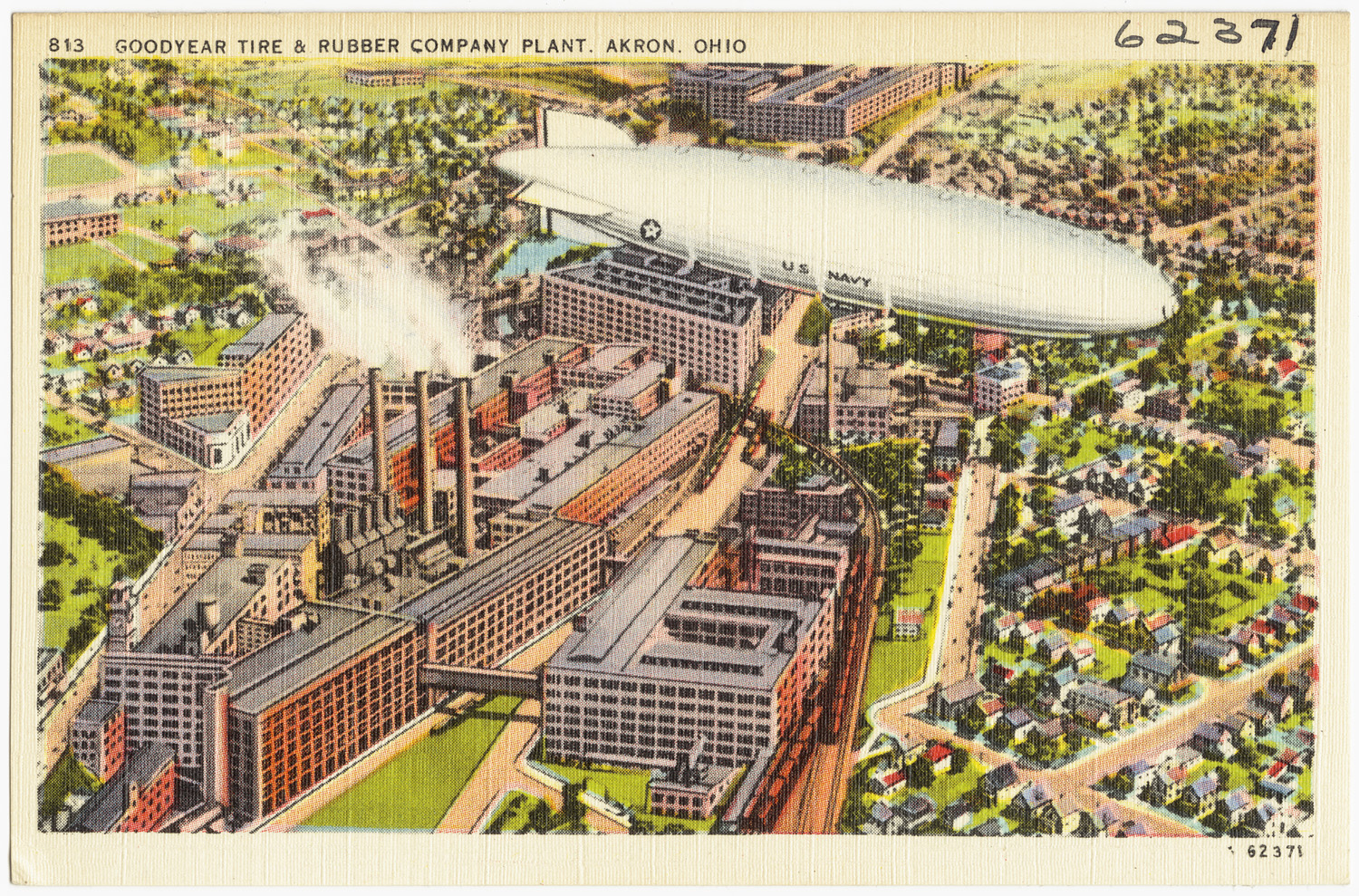

Appalachia provided much more than the fuel for northeast Ohio’s steel furnaces though. Beginning in the early 1900s, mountaineers increasingly fed the region’s hunger for labor as they migrated north for work. Driven by local rubber companies’ desire for “native” labor, Akron in particular became an early destination for Appalachian migrants. The city earned the nickname “Capital of West Virginia” thanks to its tens of thousands of Mountaineer residents.

However, Appalachian newcomers weren’t always welcomed. Migration led to overcrowding and competition for jobs, and Akronite workers soon invented the derogatory nickname “snakes” for West Virginians. Nevertheless, Appalachians integrated into community life. In 1916, migrants formed the West Virginia Society, which hosted a popular annual picnic until at least the 1970s, and West Virginians were often at the forefront of labor struggles in Akron during the 1930s.

Less admirably, white migrants were also involved in explicitly racist organizations. Kentucky migrant Dwight Billington formed the segregationist Akron Baptist Temple to cater to Appalachian migrants in 1934, and the church claimed over 15,000 members by 1949. Although not an explicitly Appalachian phenomenon, Akron’s large white Protestant population also helped it develop America’s largest Ku Klux Klan chapter (with over 50,000 members) in the 1920s, with the Klan controlling most local offices.

As recounted elsewhere, the stream of migrants leaving Appalachia in the early 20th century swelled to a flood in the 30 years after World War II. Of the 7 million migrants who left Appalachia between 1940 and 1970, 1 million of them ended up in Ohio. Northeast Ohio industrial firms in towns like Elyria and Lorain recruited heavily among West Virginians and in 1970, approximately one-third of Ohio factory workers were Appalachian migrants. By 1973, Cuyahoga County alone was home to 100,000-120,000 Appalachians.

In addition to being important population-wise, northeast Ohio was also an important place for Appalachian migrant organizing. In the late 1960s, Cleveland was the birthplace of the Eastern Kentucky Social Club, founded by black migrants from the Kentucky coalfields. Arguably the most successful Appalachian migrant group in history, the EKSC differed from other migrant groups like Akron’s West Virginia Society in its expansion beyond a single city. As of 2012, the organization had fifteen chapters across the United States and it celebrated its 45th annual reunion in 2014.

Although insignificant in absolute terms, sparsely populated Ashtabula County also received its share of Appalachian migrants during this period, creating a migrant community lovingly documented in Carl Feathers’ Mountain people in a flat land: a popular history of Appalachian migration to northeast Ohio. Published in 1998, the work is interesting for its portrayal of the move to Ashtabula as a definitive move out of Appalachia to a new life in northeast Ohio, Little did Feather know, just a decade after the book’s publication Appalachia would expand to include Ashtabula as well.

The port of Ashtabula on Lake Erie in Ashtabula County, Ohio. Considered a destination outside the region in 1998, Ashtabula was subsequently added to the Appalachian region in 2008. Via Wikimedia Commons.

While some may see the ARC’s 2008 expansion as having no bearing on the “real” Appalachia, the decision’s effects can already be seen in discussions about the region. The emerging Northern Appalachia movement uses the ARC map as its point of departure, and a Youngstown literary organization was included in the movement’s 2019 conference. Northeast Ohio counties now have access to funding to promote Appalachian culture, and the area’s inhabitants are expressing renewed interest in their mountain heritage. Even people who supposedly “know better” are writing about northeast Ohio as if it were Appalachian.

All of this isn’t necessarily to argue for northeast Ohio’s inclusion in Appalachia, although neither is it to raise the alarm about all of the flatlanders we’re letting in. Instead, it is to illustrate that what is ‘Appalachian’ isn’t written in mountain stone. Rather, it is the outcome of ongoing, often fierce debates about who gets included in and excluded from Appalachia’s story. Some may look at the ARC map and scoff at the idea of including flat land in a mountain region. Others may see northeast Ohio’s Appalachian connections as earning it a place at the table.

However these debates shake out, what matters is that we recognize that where we draw the line around Appalachia and how thickly we mark it is a choice; one people may make for different reasons, but one that almost always has important implications. Contrarily to those behind the 2008 ARC expansion, we would do well to think deeply about those we let in and those we leave out in drawing our own lines around the region.

This article is based on a talk Nick Brumfield is slated to give on Appalachians in northeast Ohio at the Massillon Public Library in Massillon, Ohio on October 29, 2019. Find out more and RSVP here.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nicholas Brumfield is a native of Parkersburg, WV currently working in Arlington, VA. He is also a 2007 recipient of the West Virginia Golden Horseshoe for exceptional knowledge of West Virginia history. For more hot takes on Appalachia and Ohio politics, follow him on Twitter: @NickJBrumfield.