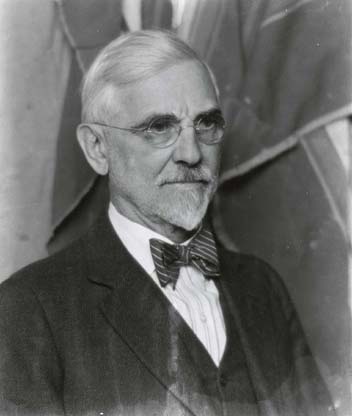

Joseph Henry Sharp came from humble beginnings. Born to Irish immigrants in 1859 in Bridgeport, Ohio across the river from Wheeling, West Virginia. He would live to the age of 93, becoming an internationally acclaimed artist who traveled widely and shaped the popular image of the American West.

Today, Sharp is not a household name, but his paintings hang in the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution, the New Mexico Museum of Art, and the Cincinnati Art Museum, among others across the United States.

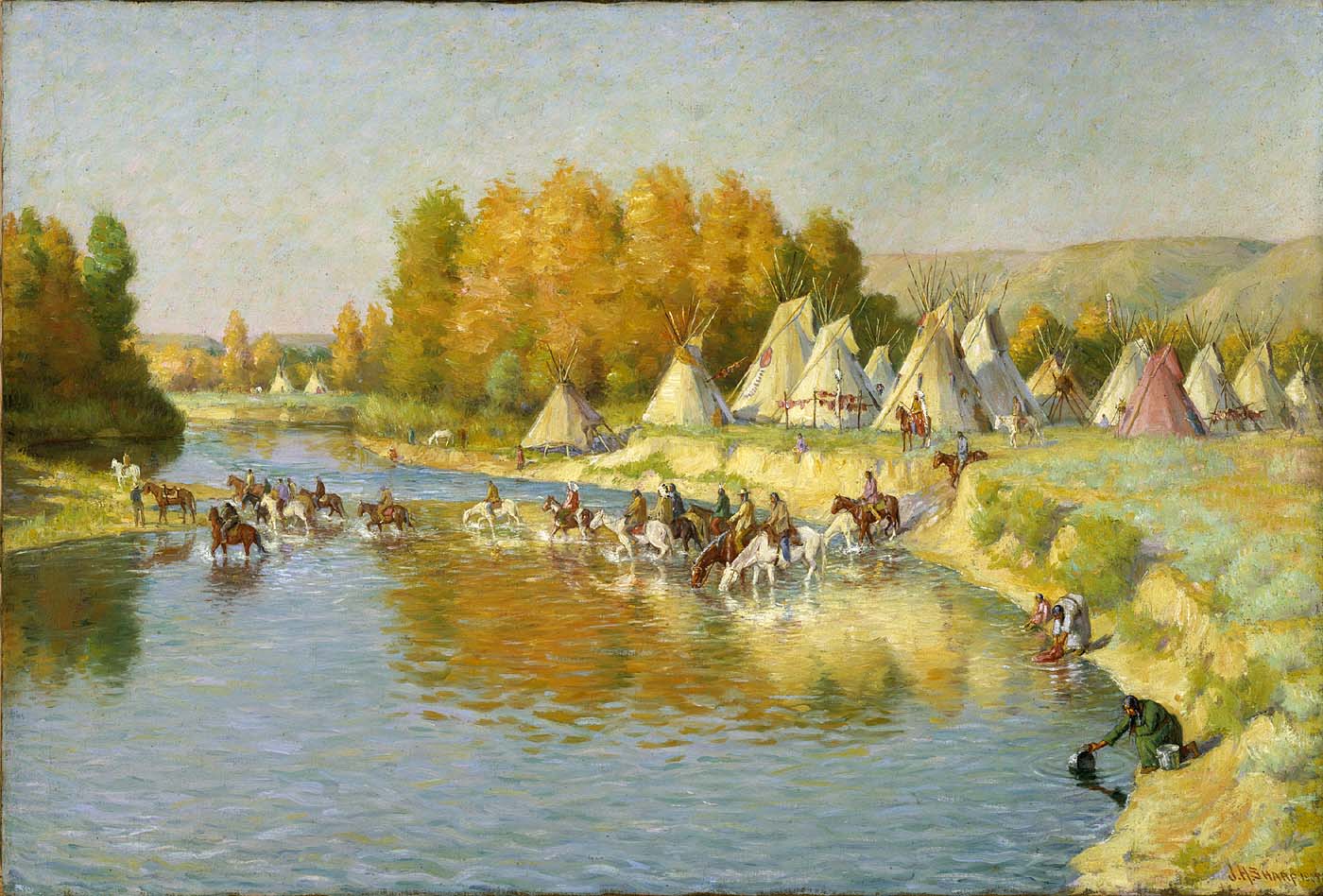

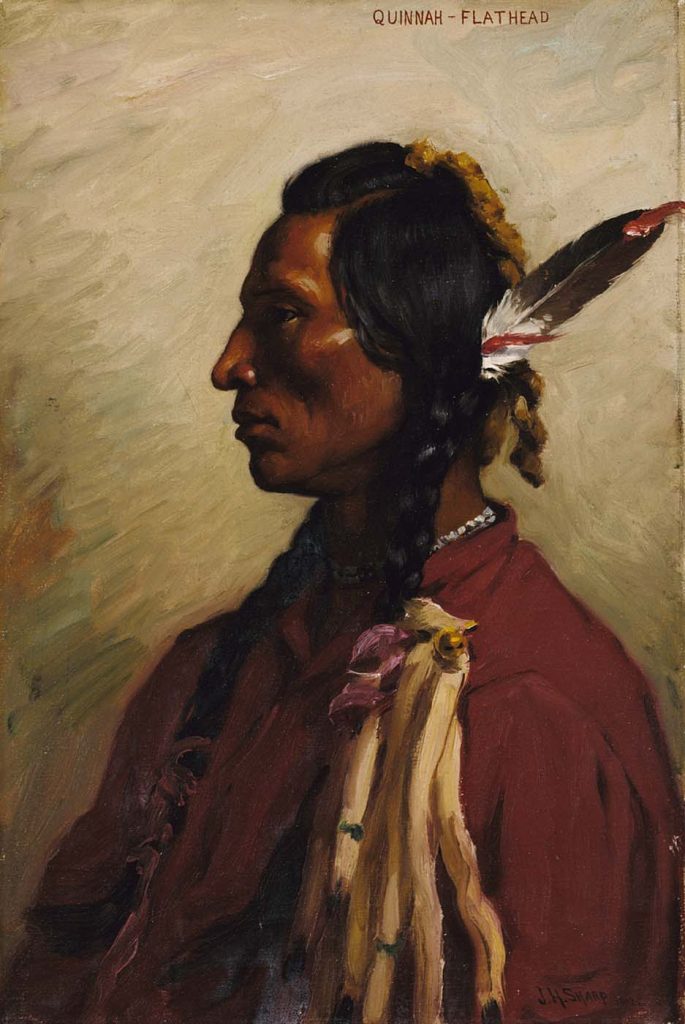

Sharp is best known for his portraits of Native Americans in Montana and New Mexico: He painted many warriors from the Crow people who had fought in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, where George Custer was killed and the 7th Cavalry of the U.S. Army was defeated in 1876. An exhibition of his portraits garnered the attention of the Smithsonian, which purchased 11 portraits, and Phoebe Hearst, daughter of William Randolph Hearst, who bought 80 portraits and commissioned another 75.

Before his fame, though, Sharp stayed in Ohio through his 20s. He went to work at a nail factory and copper shop at 12 years old when his father died, then quit school and moved to Cincinnati at 14. For the next eight years, he worked and supported his mother while studying art. His artistic talent was great, but he needed to go beyond Ohio to complete his education. A two-year stint at the Antwerp Academy, in Belgium, would be his first trip abroad, and throughout the 1880s, he visited Munich, Paris, Italy, and Spain to better his technique and knowledge of art. Through his involvement in the Cincinnati art scene, he met other artists who would go on to great fame, such as Frank Duveneck and John Hauser.

In 1890, Sharp, Duveneck, and Hauser founded, along with 10 other artists, the Cincinnati Art Club, at a time when Cincinnati’s reputation for art reached its peak. Sharp would teach at the Art Academy of Cincinnati for the next dozen years, taking trips to the West and Europe with other artists. His fame soared in 1900 when his Native American portraits were exhibited in Paris and Washington, D.C. Sharp would take trips to Montana and New Mexico, making sketches of Native American life and portraits when not teaching in Cincinnati, then complete his paintings back at his studio.

By the end of the decade, Sharp moved out West full-time, living in Montana and then in Taos, New Mexico, where he bought an old chapel to serve as his home and studio. Once Sharp gave up teaching thanks to the sale of his portraits, he devoted more time to his studio and his painting output greatly increased.

He had first visited Taos in 1893 and encouraged other artists to follow him there, turning the small Pueblo settlement into an art colony. It was from Sharp’s efforts that the Taos Society of Artists was formed in 1912, the first regional school of painting in the West. The TSA ended in 1927, but the town remains an art colony that attracts visitors.

Sharp died in 1953, leaving behind more than 10,000 works of art, almost 8,000 of them focused on Native Americans, and more than 3,000 portraits.

Sharp’s life was characterized by movement. He stayed rooted in Ohio long enough to develop as an artist and form bonds with other local artists, and laid the groundwork through the Cincinnati Art Club to train young artists and keep Cincinnati’s art influence alive. Europe’s grip on the art world, however, pulled him and others across the Atlantic. German immigration to Cincinnati was especially important for tying Cincinnati and Munich’s art scenes together. The Cincinnati native Frank Duveneck, for example, was the lynchpin for turning Munich into a hub for American artists when he moved there in 1870.

The sons (almost always sons, except for Pittsburgh native Mary Cassatt, who went to Paris in 1866) of German immigrants chose Munich over Paris for their art education because they were familiar with the language. American artists who improved their artistic skills in Europe paid dividends for the U.S. when they returned home. “Equally important was the impact some of the Munich men had as catalysts in the new art world forming in America, many of them serving as influential teachers,” Joshua C. Taylor noted in The Fine Arts in America. The Cincinnati Art Club and, in New York, the Society of American Artists and the Art Students League all were founded or benefited from young American artists traveling across country and continent. Given his early experience with the Cincinnati Art Club and the expectation of artists to travel and form associations, it’s no surprise that Sharp would form another group in New Mexico two decades later.

Sharp’s focus on Native American imagery was historical as much as it was artistic. “Sharp felt an urgent need to capture the spirit of these Indians and to document their lives before an era passed,” Bruce Eldredge, Nell Horton, and Janis Ziller Becker wrote. In Forest Fenn’s The Beat of the Drum and the Whoop of the Dance, Fenn quoted Sharp reflecting on his work:

I was first attracted to the human side of the Indian; the character of the old warriors I found particularly interesting. Their romance and idealism are the most beautiful symbols brought down in the annals of time; their religion, their legends and superstitions are all unique. Not these alone, however, brought the greatest influence to bear on my work. It was more the humanity of the present, the aspect we can see, know and feel that was my greatest inspiration.

Fellow painter Ernest Blumenschein, at Sharp’s memorial service in 1953, said that “He was the reporter, the recorder of the absolute integrity of the American Indian.” Sharp’s art wasn’t a reductionist glance at the West, watching the disappearing Native American tribes fighting white Americans encroaching on their land. He lived for months at a time on Native reservations year after year, bringing personality into his portraits. But he did benefit from the American public’s interest in Native life and customs—after the country’s expansion left them little land and a way of life forever changed. “Sharp captured the individuality of his subject,” wrote Marie Watkins, associate professor of art history at Furman University. “In a broader art historical framework, the subject matter of Sharp’s monotypes reflects a nation in transition, attracted to nostalgic American themes of a timeless past.”

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Anthony Hennen is co-founder and managing editor of expatalachians and managing editor at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal in Raleigh, North Carolina.