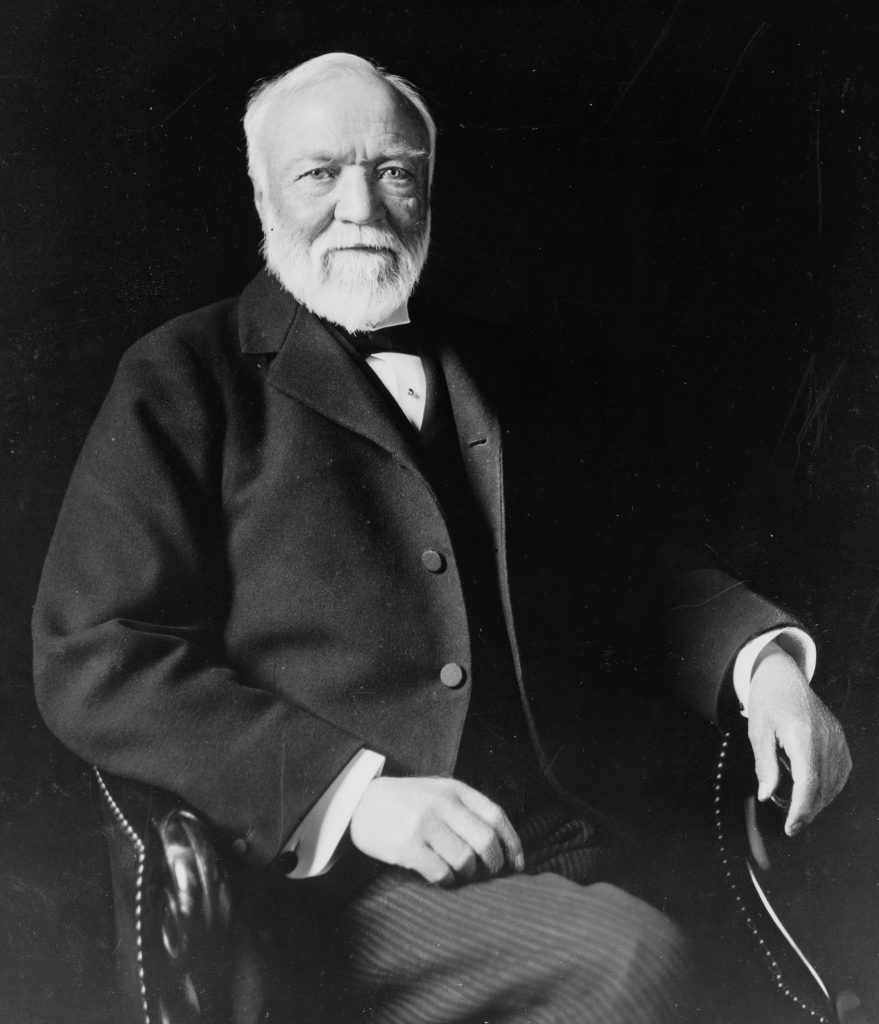

Andrew Carnegie earned his fortune in the steel industry. Born in Scotland in 1835, Carnegie arrived with his family in New York City at the age of 13 in 1848. The voyage across the Atlantic lasted 50 days, and the journey to their final destination, Pittsburgh, took another three weeks. Pittsburgh at that time was a bustling, albeit filthy, industrial city. “Hell with the lid taken off,” is the visceral description that The Atlantic journalist James Parton used to describe an extremely smokey and polluted Pittsburgh in 1868. This was also the setting in which a young Carnegie transformed from a boy into a steel tycoon.

From working in a cotton factory to becoming the superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Carnegie’s hard work and aptitude for profitable investing led him into the steel industry in the early 1870s. Eventually he sold his company, Carnegie Steel Company, and decided to spend the rest of his life giving away his fortune. This led him to fund the building of 1,689 public libraries across the country and become the “Patron Saint of Libraries.”

Unusual for a millionaire, Carnegie believed that the rich were mere trustees of wealth and therefore had “a moral obligation to distribute [their money] in ways that promote the welfare and happiness of the common man.” He penned this statement in “The Gospel of Wealth,” an essay detailing his philosophy of philanthropy. The essay is particularly famous for the quote, “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”

Carnegie certainly did not die poor, but his philanthropic gifts live on today. Since Pittsburgh was where Carnegie built his career, the city received special attention. Examples of his philanthropy in the city include Carnegie Mellon University, the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, and of course, the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh (CLP).

As generous as Carnegie’s gifts were, he left a controversial legacy. Biographers have noted his brutality, such as his involvement in The Homestead Steel Strike of 1892, arguably the worst labor conflict in U.S. history. The strike ended after a confrontation between Pinkertons (agents from a security company) and striking workers resulted in deaths on both sides. Carnegie and plant manager Henry Clay Frick contracted the Pinkertons with the intention to destroy the labor union, which ultimately happened thanks to events that ensued after the strike.

Despite this part of his legacy, Carnegie is generally regarded in a positive light in Pittsburgh. “While the riverfront steel mills of the Mon Valley are mostly gone now, the generosity of industrial giants like Carnegie and Frick…lives on in a legacy of art, culture and education in Pittsburgh,” Visit Pittsburgh declares on its website. Thus, the brutality of Carnegie’s actions are often forgotten or underplayed in a city that exists in great part because of the steel industry and philanthropic donations from Carnegie.

Carnegie’s libraries remain one of the most visible parts of his legacy: 19 exist in Pittsburgh, along with many more county branches.

“He [Carnegie] gave the seed money to create the library but expected the community to support it,” said Suzanne Thinnes, manager of communications at CLP. Therefore, the collections and services CLP offers today were built by and for the community.

All the libraries offer residents an endless selection of books and access to online databases, community services, and activities. Although each library has its own collection, every Carnegie library in the county shares resources. Someone living in the suburbs, for example, can borrow a book from a city library using the same library card and vice versa.

“In addition to books, we have music and movies. We offer a lot of programming to the community for free. We have yoga and tai chi, for example, and we offer language classes,” Thinnes said. Other programs include sensory story time, homework help, meditation with a monk, and job and career assistance.

In 2020, CLP will be 125 years old. This milestone is a testament to the dedication of the Pittsburgh community and the vision of Carnegie, who believed in the power of libraries to educate and uplift communities. As he said, “A library outranks any other one thing a community can do to benefit its people. It is a never failing spring in the desert.”

Annie Chester is a writer and co-founder of expatalachians. She writes on environment and culture in Appalachia and abroad. She was an English teacher on the Island of Corsica, France. Now, she’s an Appalachian Food Justice Fellow.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.