Before a disease or health issue goes national, it tends to first appear along the spine of the Appalachian mountains.

“You can look at how diabetes has spread and you can look at how obesity has spread out over the country,” David C. Gordon of the University of Virginia Health System said. “So goes Appalachia, so goes the rest of us.”

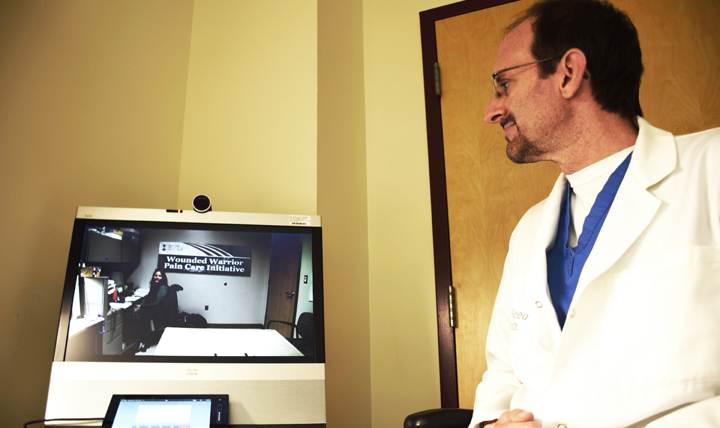

The difficulty of getting health care to rural residents in Appalachia has created another opportunity to lead the country, but in a better way: By using telehealth, or technology for remote access to and management of health care. Instead of requiring patients to make the long journey to a doctor’s office, telehealth allows them to seek care at smaller clinics or monitor health issues from home.

Gordon has long been involved in health care in the region as the director of telehealth for the Karen S. Rheuban Center for Telehealth at UVA. As he sees it, telehealth has the potential to make health care more accessible to people outside cities, improve the quality of health care they’re offered, and engage with people where they are.

“This is first and foremost about access to care where it is otherwise unavailable,” Gordon said.

Telehealth gives rural or limited-mobility patients the chance to interact more regularly with doctors. Rather than going weeks or months between check-ups, they can send health information to their doctor hours away on a daily basis. Checking on a diabetic patient, for instance, becomes much easier.

Expanding telehealth use can also allow nurses and other medical workers to do more. Instead of a physically present doctor, a nurse or medical assistant can provide health care at remote clinics, then call the doctor on a secure line to sign off on the care. As rural communities struggle to attract doctors, telehealth fills the void. It can also give local health workers training and experience, making the problem of doctor shortages in the region less severe.

“We didn’t plan on staying here, but we did,” said Paula Hill, a family nurse practitioner and the clinical director of the Health Wagon, a nonprofit that provides mobile health services in southwest Virginia. She and Executive Director Teresa Gardner Tyson grew up in the region and continue the work started in 1980 by Sister Bernie Kenny, a Catholic nun from the order of Medical Missionaries of Mary.

The Health Wagon provides health care from a mobile unit to six counties across southwest Virginia and two stationary clinics. Hill said they served more than 16,000 patients last year in a part of the state that has above-average poverty rates and a life expectancy that is 10 years fewer than Virginians in the richest part of the state, Fairfax County in the Washington DC suburbs.

“[Telehealth] has helped our patients tremendously. Even if you have health insurance and you’re living here in southwestern Virginia, it’s a 2-hour drive to get into the nearest endocrinologist, for example,” Hill said. Telehealth is “bringing health care to the people, to the communities that they live in, making it possible for them to receive access to specialists that are otherwise totally unavailable to those without insurance—and very restrictively available to those even if you have insurance, and that’s because of the lack of transportation here.”

At the Health Wagon, nurse practitioners use telehealth for colostomy care and treating diabetic ulcers, to conduct ultrasounds and x-rays, to offer specialty psychiatry care, and even once to deliver medicine via drone. “We use it for everything, to be honest,” Hill said.

That resourcefulness with telehealth also gives the Health Wagon a chance to innovate. A pilot program to treat opioid abuse in the region, Hill said, is being planned in partnership with the University of Virginia and the commonwealth’s attorney office. It involves running a medication assisted treatment center to avoid the misuse of suboxone, a drug used to treat patients addicted to opiates.

One problem with suboxone is substitution, where patients would become dependent on suboxone instead of being weaned off drugs completely. Another is selling suboxone on the street instead of using it as prescribed. In the pilot program, patients will be given subutex, an injectable form of suboxone. The idea is that patients cannot abuse or sell it because it is administered in-person, so diverting the drug for a non-intended use becomes impossible. If successful, the program can then be expanded statewide.

Expanding access and encouraging innovation has been a strong selling point for telehealth, but it can also lower costs. Being able to renew a contact lens prescription online, for instance, saves people time and money. Allowing pharmacists to prescribe some medication, such as birth control, lets doctors focus on more important medical questions instead of forcing people to go through a doctor’s office for a routine medical need. Those marginal gains can have a big impact overall.

For telehealth to improve health care outside cities, however, the regulatory environment needs to change. The sprawling health care system has many barriers baked in to limit harm, but they can also limit telehealth, said Jarrett Dieterle, director of commercial freedom at the R Street Institute, a public policy research organization. Current regulations “often will be kind of resistant to it in certain ways,” he said. “Some of the biggest barriers, basically it’s a new technology and the current regulatory regime, licensing regime for the medical field has yet to fully catch up.”

For instance, “asynchronous medicine,” which is when test results are reviewed later instead of immediately, is generally forbidden. Many states require real-time evaluation, Dieterle said, even though patients would not suffer from the delayed or off-site evaluation. Professional licensing, too, restricts doctors from caring for patients across state lines. A licensing compact has been approved by 26 states to loosen some state-based restrictions, but many limitations remain.

Territorial disputes among health care workers stifle telehealth, too. “Doctors can often be really reluctant to let in more competition into the field, even though doing so would be good from a consumer’s standpoint,” Dieterle said. “It would increase access, lower costs, and…there really wouldn’t be any danger to health and safety by doing so because it’s usually stuff that these other health professionals are trained to do.”

Those licensing restrictions fall under the “scope of practice” umbrella. They can benefit doctors, but bring no benefit to patients and limit the services other health care workers can offer, such as when Georgia optometrists lobbied to ban online eye exams.

All the moving parts of health care can complicate telehealth expansion. State and federal policies need to allow innovation. Making telehealth costs billable needs to be negotiated with insurance providers. Creating agreements between facilities and hospitals, too, is important so that telehealth will actually be used instead of only talked about. All of those changes are also subject to protecting patient privacy and medical confidentiality.

The different approaches to health care among the states can give other states models for how to proceed in adapting to the needs of their citizens. Gordon mentioned the early work in Alaska, Hawaii, Kansas, and South Dakota in making telehealth viable. Dieterle pointed to how Indiana clarified state law about ocular telehealth. If state legislators can focus on how remote health care can improve rural access to and ignore insincere concerns about “health and safety” that preserve the status quo, rural residents can benefit from those innovations.

When the University of Virginia got more involved with telehealth, Gordon said, their medical school conducted a transplant operation on a Saudi Arabian princess. And “it was a hoop-de-doo:”

We connected back to Riyadh in Saudi Arabia. And the president of the university, in his annual report, thought enough of it to make mention of that. And it wasn’t much time before a state senator from the region picked up the phone in the coal fields and said, you know, “What the hell? If you can go to Riyadh, you can come to Pound, [Virginia].”

As the University of Virginia’s health system has expanded into a “spiderweb of locations,” Gordon said, Pound now feels closer to Charlottesville. The disparity among health outcomes in urban and rural places remains, but telehealth could provide the tools to narrow it and make access one less problem.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Anthony Hennen is a co-founder of expatalachians and editor/writer at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal in Raleigh, North Carolina.