The Underground Railroad was a network of routes, people, and places that enslaved Africans and African-Americans used to escape slavery. This network functioned before the Civil War (1861-1865) but slowed after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which mandated the return of an escaped enslaved person and fines and imprisonment for anyone who aided them regardless of race.

The majority of people fleeing enslavement were young, single men aided by free African-Americans in the North. As author and historian Eric Foner noted during an interview with public broadcasting station KQED, few people escaped from the Deep South; most fled from states bordering the North, such as Maryland and Delaware. Escapees developed inventive methods to leave enslavement. They disguised themselves as free men and took trains or steamboats North or stole their enslaver’s horse-drawn carriage. One man, Henry Box Brown, escaped by shipping himself to the North in a wooden crate. Thus, the railroad was a network of routes north, rather than a prescribed singular path to freedom.

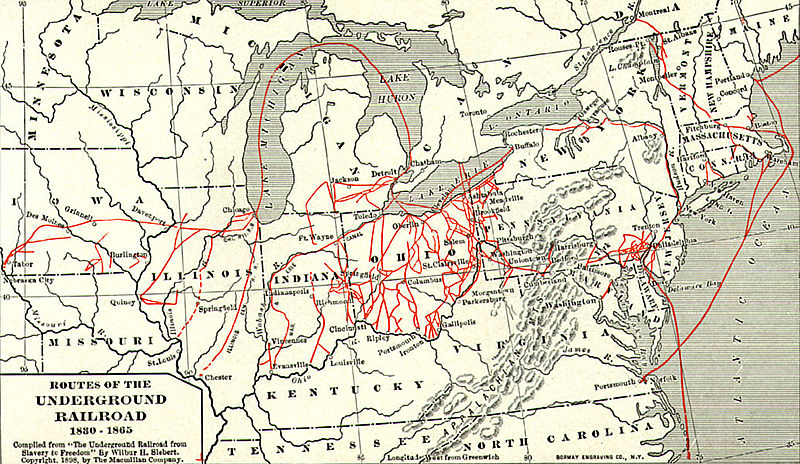

“Routes of the Underground Railroad, 1830-1865.” Via Wikimedia Commons.

In honor of Black History Month, expatalachians talked with Pittsburgh-based artist Kelsey Robinson about her current project focusing on the Underground Railroad. In the multimedia project “Talking with Ghosts About Freedom,” Robinson and collaborator Di-ay Battad explore the history and culture of enslaved people as they journeyed toward emancipation. The duo debuted a prototype performance at the Kelly Strayhorn Theatre in Pittsburgh in November 2018. They also created a video, which documents their journey via bicycle from Pittsburgh to New Brighton, Pennsylvania. Filmed and edited by Battad, the video focuses on Robinson’s experience while weaving in a soundscape of natural and industrial sounds captured on the road.

What follows is an edited version of the conversation with Robinson on her motivations, the importance of history, the role of Appalachia in the Underground Railroad, and the future of the project.

Why did you decide to create this project?

I’ve wanted to do this for over 10 years. I love bike touring, and I thought this would be an incredible trip to do in honor of my ancestors–my Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. Then as I was backpacking in South America, I started to understand how big a part place plays in defining the music of that region. After getting to know indigenous people who had this really strong understanding of how, where, and who evolved music in that area, I realized I didn’t know enough about that in my own country and culture. That’s when I started thinking of this as more of a process of gathering this information and learning more about the evolution of Black music.

I started to read different slave narratives, and I realized in doing so that we’re more accustomed to hearing about an enslaved person’s experience from the third person. It’s not that first person accounts don’t exist. They just aren’t circulated as widely, especially the ones that aren’t known figures in the abolitionist movement.

Do you mind talking about the research you did prior to the test run of what will be a larger trip?

I read a lot of accounts from the Federal Writers’ Project of Slave Narratives, Zora Neale Hurston’s interviews with Cudjo Lewis in the newly released Barracoon, and William Still’s book, The Underground Railroad Records. Still, a Philadelphia man born free in 1821, worked for the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society and was instrumental in helping hundreds of enslaved people escape through Philadelphia. He kept really specific records about the people he was helping, and he would hide them in crypts in the cemetery.

I also worked with the Heinz History Center [in Pittsburgh] and Samuel W. Black, curator of the permanent exhibit “Slavery to Freedom.” He walked me through his exhibition and shared with me information about particular tools and labor practices used for different crops, the types of plants enslaved people foraged and used as nourishment and medicine, and the impact of different laws as they were passed. I was also very fortunate to spend some time with curators and programming staff of the African American Museum in Philadelphia and the National Museum of African American History and Culture in D.C.

What was interesting in the research you found?

There was one story I used in a show about this enslaved woman in Virginia and her enslaver would force her to knit standing all day. When she would start to get tired and fall asleep standing up, she would get cracked over the head. That imagery really stuck with me. You can’t even begin to conceive that type of cruelty because it’s so arbitrary.

Another thing that I think is really amazing was the way people would speak about freedom and liberty as if it was divine, or even feminine meanwhile nobody knew what it was but they were willing to risk everything.

Why is it so important to tell history, especially in the way you have, by walking in the literal footsteps of history?

I think as a nation we are so far removed from history. So many people consider us to be in this post-racial world, but so few of us really know enough about the racial world. I think that we sweep all of this history under the rug, and that contributes to people being confused and angry and unable to see eye to eye.

If these stories were shared and lessons were taught, there would be more understanding as to why we are where we are and why we still have so much work to do. Understanding how much slavery played into the infrastructure of this country and to understanding why reparations are still so due.

What role did Appalachia play in the Underground Railroad?

You know, a lot of the Underground Railroad takes place by water side instead of by mountain side. I think there was probably a lot more marooning (the act of living in areas of forest and swamp previously uninhabited) and maroon settlements that were established in the Appalachians because people found hidden pockets of land where they could live and hide.

If we’re talking about the region of Appalachia and not the mountain range, Pennsylvania and New York being so near to the Mason-Dixon line had a lot of organized efforts that were really pivotal for creating safe routes to freedom. This all changed with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Then, even enslaved people who had managed to successfully escape were no longer safe in the North.

What does art add to the retelling of history?

A lot of historical re-enactments and history books are really boring, in my opinion. I think a lot of times what makes it so boring is the fact that it’s not being told in the first person. It’s way more interesting to hear someone talk about their own life when the stakes are higher, when they are talking about their own pain, their own fears and triumphs.

Before this project, I would never have said I’m a history person, but now I am. And I want to create more work that’s based on history and anthropology because it is so important, and it is fascinating when it’s told the right way.

Why is this project important to you?

I want to know more about my own ancestry and peoples. I want people to see women of color on their bikes making this trip. But, also, it’s the first time I’m trying to marry all of these things that really fascinate me into one project. I’ve dreamt of this project for so long and it’s so much bigger than I am because of all of the history and the other people and institutions that are involved.

What do you hope your audience learns from this project?

I hope that they hear more of these stories about resistance. So often we hear the stories about the kind of suffering and victimization that enslaved people had to live with, but we don’t necessarily hear about all of the planning, brother and sisterhood, secrecy, action, and attempts that were being made to seek freedom. It wasn’t just like one day someone decides, “I’m going to run”— there were uprisings being planned over years. I want people to hear more of these stories.

What does the future of this project look like?

I have been collecting the resources to take the trip and finding different galleries, museums, farms, and studios that want to host me and my collaborator. As of now we have some cool partnerships in New Orleans, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, and New York.

The trip is scheduled for May until around the end of September. It will definitely take three to four months. There is a possibility that we will push it back depending on the development of an interactive digital component.

For more about Robinson’s project, check out the website: https://www.talkingwithghosts.com

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.