For many in Appalachia, the last few days have been crazy. Amid fears of coronavirus, states across the region are shutting down society to slow the virus’ spread. Authorities are closing schools, experts are advising us to socially distance ourselves, and people are panic-buying toilet paper. The situation can be scary and isolating; at times, it can seem like we’re living through unprecedented chaos.

It is in times like these that we would do well to remember our past. Though it may seem like the end of the world, history can show us we’ve been here before. It can show us stories of the brave men and women who rose to the challenge of their times, and, perhaps most importantly, it can show us how the current crisis can end.

In this spirit, and in honor of Women’s History Month, let’s revisit another time when Appalachia faced a situation of this magnitude, the 1918 Spanish Flu, and remember the often-forgotten women who served as nurses during history’s worst pandemic.

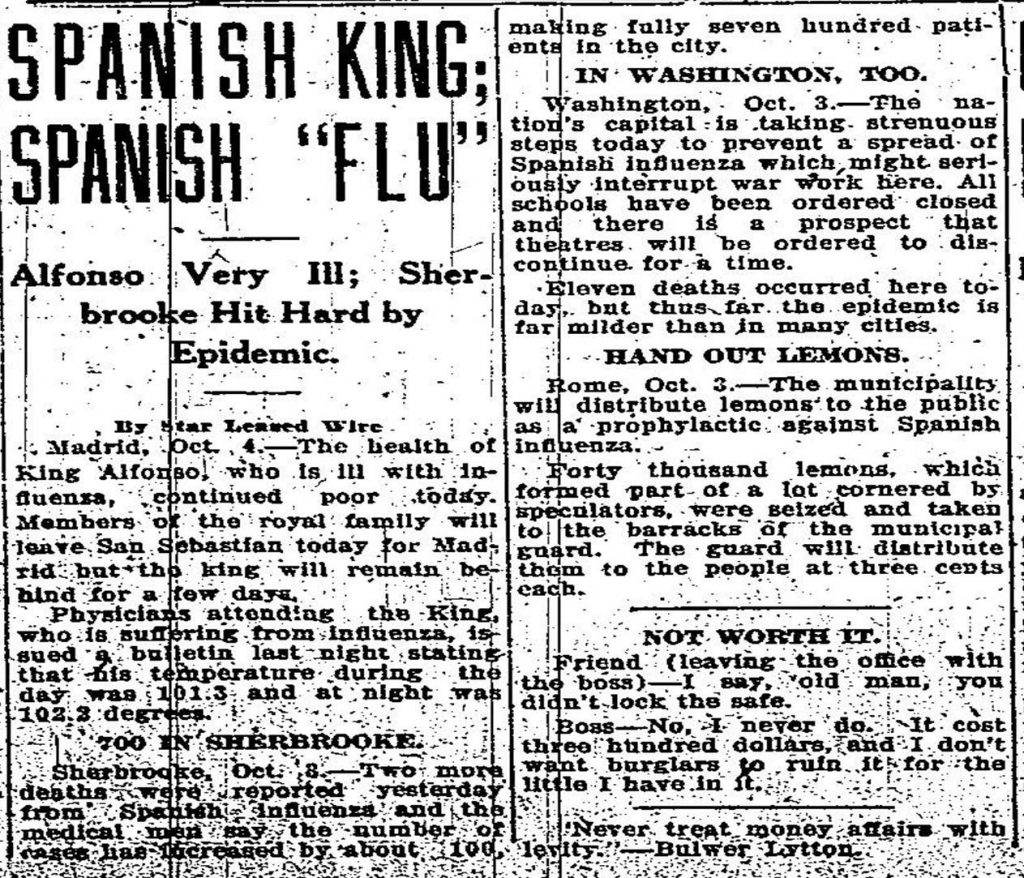

Although there is some debate about where the Spanish flu originated, one thing is clear: it wasn’t actually Spanish. Due to censorship in most other Western countries during World War I, the press in neutral Spain was the first to widely report on the illness, and the name stuck. In fact, the most popular theory for the flu’s start places its origin in America’s heartland near Fort Riley, Kansas in March 1918.

At first, the virus went largely unnoticed in the buildup to the US involvement in World War I. Although some doctors reported a new strain of severe influenza in the spring of 1918, often coupled with bacterial pneumonia that led to an excruciatingly slow death by suffocation, America was focused on the war.

So, without much attention, the Spanish flu spread. Much like COVID-19, the Spanish flu spread through droplets of saliva released by coughing and sneezing that could be spread via handshake, affected surfaces, or directly to those within close range. Soon enough, the virus spread to the soldiers at Fort Riley and, as they deployed to Europe, the world. It would only be when the virus returned to America in a second wave in the fall of 1918 that the country would truly feel its effects.

As a field, nursing was also rapidly developing in the lead-up to the war. Originally a service expected of women as part of their domestic duty to tend to the sick, in the half-century after the Civil War, nursing became an increasingly professionalized occupation. Most Appalachian states established nursing schools and associations during this period where women could develop specialized medical expertise, even as they were largely excluded from becoming doctors. By 1918, the US had about 98,000 “graduate nurses” certified by the Red Cross.

But those numbers weren’t enough for the war effort. “The War sucked up nurses as it sucked up everything else,” historian John M. Barry wrote, and more than 16,000 nurses were serving in the military by May 1918. The hunger for military nurses pulled them away from the civilian health infrastructure, setting up a major nursing shortage that would affect much of the Spanish flu response.

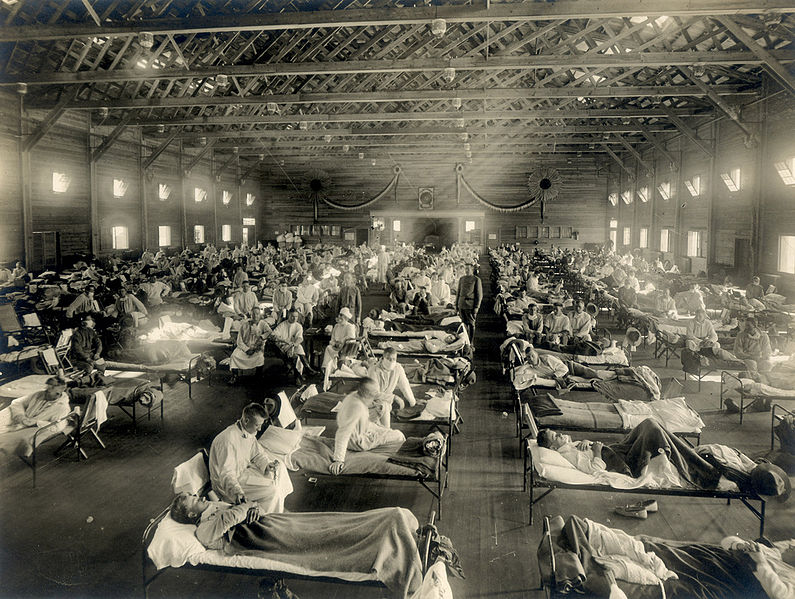

The second (much deadlier) wave of Spanish flu began in August, when cases popped up in ports like Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and Seattle. From there, it then tore across the country, often carried by soldiers moving around for the war effort. In late summer 1918, thousands of soldiers contracted the disease at Camp Sherman near Chillicothe, Ohio, which saw almost 1,200 deaths before the epidemic ended. Kentucky reported its first case on September 22, West Virginia suffered its first death on September 26, and by early October, regional centers like Knoxville and Pittsburgh were reporting hundreds or thousands of cases a month.

Due to its rural setting, many hoped Appalachia might be spared the worst of the epidemic. It wasn’t. Although rural areas were hit by the virus later than urban areas, the flu was devastating when it arrived. Many areas’ poverty and poor infrastructure hampered the response. A week after a local official praised Big Stone Gap in Virginia for containing the virus, the local newspaper reported it was “the worst afflicted of any part of the state.”

Soon enough, much of the central Appalachian coalfield was in the grips of the flu. One Kentucky miner later described life in a coal camp as a time of desolation:

And that, that epidemic broke out and people went to dyin’ and there just four and five dyin‘ every night dyin’ right there in the camps, every night. And I began goin‘ over there, my brother and all his family took down with it, what’d they call it, the flu? Yeah, 1918 flu….nearly every porch…would have a casket box a sittin’ on it. And men a diggin’ graves just as hard as they could and the mines had to shut down…there wasn’t a mine arunnin’ a lump of coal or runnin’ no work. Stayed that away for about six weeks.

Faced with this massive health crisis, but without any means of treating it or vaccinating the public, Appalachian communities turned to many of the same social distancing techniques we use today. Local authorities closed schools, churches, theaters, and pool halls, and families were encouraged to stay home and avoid crowds. Underlining the desperate situation, communities from Knoxville to southwest Virginia banned sneezing and spitting in public under the threat of fine or imprisonment.

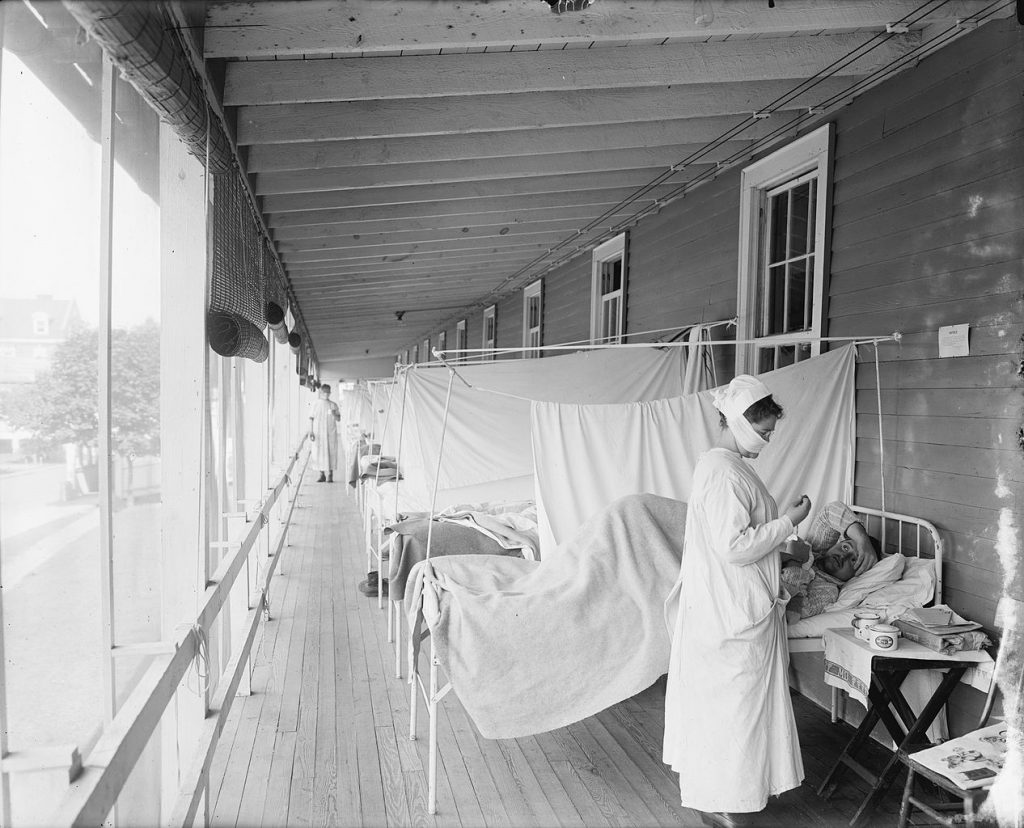

Then, as now, the heroes of the hour though were frontline medical workers. Nurses took the lead in tending to stricken communities, with their care being a major factor in whether the sick survived. Often, care took place in a patient’s home, where a nurse undertook domestic chores in addition to caring for the sick.

Wartime nursing shortages meant the job was never easy.

“You start out to see 15 patients, but instead see 50 to 60 extremely ill people before day’s end,” one nurse said. In West Virginia, women prisoners were pressed into service as nurses, and the crisis forced the Red Cross to end discriminatory practices keeping African American women out of the army nursing corps.

Despite these challenges, nurses across Appalachia served with determination, often while their male doctor colleagues were wracked with pessimism over their inability to cure the flu.

Upon arriving at a Kentucky coal mining camp of 25,000, nurse Beulah Gribble described finding all 600 of the camp’s afflicted being cared for by a single nurse, working day and night, who “had worked so faithfully under such discouraging conditions, and although…tired and overworked, she had not thought of giving up.”

Tragically, nurses often ended up paying the ultimate price in the fight against the Spanish flu. There are no estimates for nurse deaths in Appalachia, but a memorial to four nurses who died at Glendale Hospital in Marshall County, West Virginia paints a picture of who they were as people. All four were in their late teens or early twenties. All of them died over the course of about a week in late November/early December 1918, and all left behind parents to mourn them. One was from Glen Dale, another from Wheeling, another from Weston, and the fourth one’s birthplace was unlisted. Each reportedly “worked as long as she could be on her feet, regardless of her own feelings.”

The Spanish flu’s most deadly second wave ended in late 1918, but a third wave meant the country was reeling from the disease until March 1919. All told, about 500 million people around the world caught the Spanish flu during the epidemic. Death estimates range anywhere from 17 million to 100 million. Although there are no reliable regional statistics for Appalachia, 71,079 West Virginians were recorded as having been infected, of whom 2,818 died.

Over a century has passed since the Spanish flu, and there are several important differences between the flu and COVID-19. Nevertheless, studying Appalachia’s Spanish flu epidemic in light of our current experience can help us see how the region has both dramatically changed and remained remarkably the same. For instance, although social media has replaced the newspaper as our primary news source, people are still convinced the mountains are immune to disease, a belief that could have dire consequences.

More positively, women remain at the forefront of the region’s public health fight, and not just as nurses. The Director of Ohio’s Department of Health spearheading Ohio’s response to coronavirus, Dr. Amy Acton, is from Youngstown. Growing up amid adversity in a broken family, many have attributed her “unique combination of grit and grace” to her roots in eastern Ohio.

As we continue into the unknown of COVID-19, the combination of grit and grace embodied in women like Acton, and the nurses of Appalachia’s Spanish flu, is exactly what we’ll need.

For information on COVID-19 and what can you can do to protect yourself, your family, and your community, please see the links below.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Johns Hopkins Interactive Dashboard Map

Nicholas Brumfield is a native of Parkersburg, WV currently working in Arlington, VA. He also comes from a proud family of nurses, including his sister and aunt. For more hot takes on Appalachia and Ohio politics, follow him on Twitter: @NickJBrumfield.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.