In eighteen hundred and forty-four,

I landed on Columbia’s shore.

I landed on Columbia’s shore,

To work upon the railway, the railway.

I’m weary of the railway!

Poor Paddy works on the railway.

Seventeen years before the Golden Spike completed the Transcontinental Railroad in Utah, another connection was made in Marshall County, (now West) Virginia on Christmas Eve 1852. A crew of predominantly Irish laborers completed the final link of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, connecting the Ohio River Valley with the East Coast. Despite the importance of the occasion, however, little fanfare was made. After a few rounds of cheers, the weary men returned to their camps after a hard day of work.

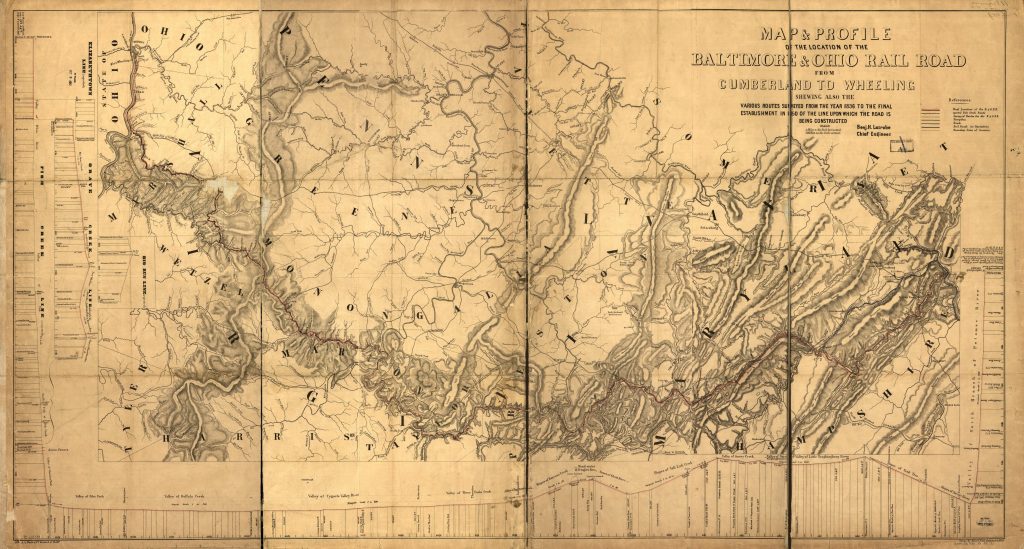

The completion of the B&O at Rosby’s Rock was the culmination of nearly 24 years of hard days’ work. Construction began in Baltimore on July 4, 1828 and continued west over rivers and through mountains for 380 miles to the banks of the Ohio River in Wheeling, (now West) Virginia. The construction of railroads was hard, back-breaking work, and was carried out by the lowest members of society. In 1840s and 1850s America, this included the hundreds of thousands of Irish peasants arriving in the U.S. each year since the Great Famine. For roughly $25 a month, those laborers built some of the largest bridges and longest tunnels in the world at that time across steep and winding terrain.

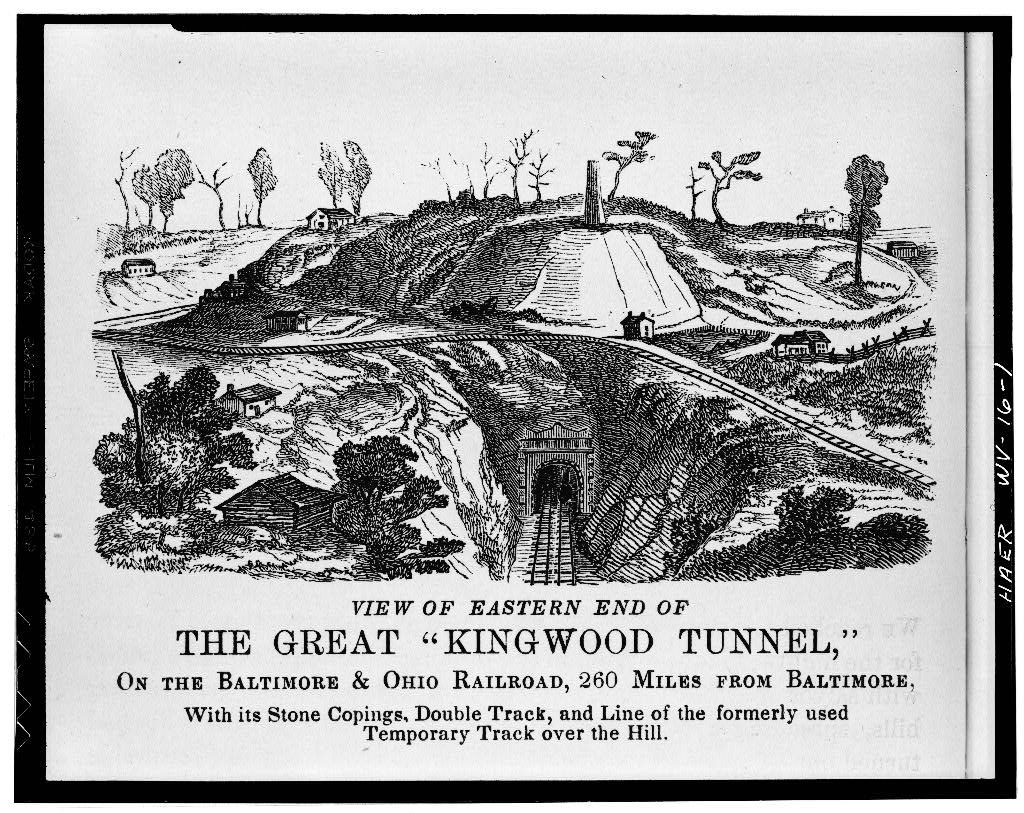

Constructed between 1849 and 1852, the Kingwood Tunnel in Preston County, WV was reportedly the longest in the world upon completion. Via The Library of Congress.

The railroad opened up the rapidly industrializing Ohio Valley to the major markets east of the Appalachian Mountains, and also connected small towns and villages along the route. Prior to the introduction of the railroad to western Maryland and Trans-Allegheny Virginia, the people who inhabited the Appalachian plateau were generally isolated, relying on rivers and primitive roads for travel and commerce.

Within the next decade, the railroad corridor between Cumberland, MD and Wheeling experienced a population boom. Early steam locomotives required frequent maintenance and refueling, and depots sprang up along the route, creating jobs and turning sleepy rural communities into bustling railroad towns. The results of the boom can still be seen today in the street names of many cities in northern West Virginia, as grateful towns named new streets—and the towns themselves—after B&O executives such as Swann, Latrobe, and Grafton.

In many cases, the increase in the region’s population was fueled by the same Irish laborers who built the railroad itself. One such immigrant was John Monahan, a member of the crew that completed the Rosby’s Rock line, who later settled in Wheeling. This pattern of laborers settling along the route occurred frequently, and the influx of Irish Catholics led to a sharp increase in the number of parishes in the newly created Diocese of Wheeling. Within two decades of the Diocese’s founding in 1850, the number of parish churches grew from four to 46 with a more-than-threefold increase in Catholics. Though Germans also comprised a large chunk of western Virginia’s Catholics, the Irish tint of the Diocese was solidified by the recruitment of priests from All Hallows Missionary College in Dublin to serve the new mountain parishes.

Beyond the railroad towns, many Irish laborers were drawn to rural communities south of the main line. Land companies in Lewis County recruited men from the railroad camps, leading to a significant Irish community in Weston, its county seat. By 1848, a new parish was created in Weston and aptly named after St. Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland.

In the decades following the completion of the Baltimore and Ohio in 1852, more railroads would forge west across the mountains into the Appalachian plateau. The Parkersburg Branch of the B&O reached the Ohio River in 1857, and industrialist Collis P. Huntington constructed the rival Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad through the New River and Kanawha River Valleys to the new river city named after him in 1873. The railroads ferried immigrants to industrializing terminus river towns and carried goods back to the East Coast. By the closing decades of the 19th century, the emergence of coal production in the region was made possible by the railroads, which created multiple branch lines to connect the coalfields and carry coal to steel mills nationwide, fueling the nation’s rise as a global power.

Along the banks of the Ohio River in Wheeling stands a Celtic high cross commemorating the Irish of the Ohio Valley. Included in the design is the logo of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and its completion date. Through the transportation of people and products, the railroads played a crucial role in developing West Virginia. By digging, mining and, hammering, Irish laborers pushed the rails through the mountains, opening the Appalachian plateau to Eastern ports, and indeed the world.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nick Musgrave first became fascinated with West Virginia’s history while growing up in Parkersburg. He continues to read, research and write on the Mountain State’s past from its birthplace in Wheeling. For more neat history and some political snark, follow him on Twitter: @NickMusgraveWV.