A once-proud mountain town down on its luck. Lush rolling hills hiding a silent crisis. An embattled community fighting for its life against the “opioid epidemic.”

It’s a story everyone in Appalachia has heard, and one that many have lived. However, it isn’t just an Appalachian story. Over 6,000 miles away, in the green valleys of the Alborz and Zagros Mountains, communities in the Islamic Republic of Iran are wrestling with the same issues. Despite recent tensions between America and Iran, the two countries are on the same side in the fight against addiction.

Home to 81 million people, Iran is a country located in the Middle East. And, contrary to popular belief, it isn’t all desert. With most of its territory located above 1,500 feet, Iran is one of the most mountainous countries in the world, with verdant green hills and mountain meadows stunningly similar to those in the Appalachian Mountains.

Unfortunately, beautiful terrain isn’t the only similarity between Appalachia and Iran. Opioid addiction has taken a massive toll on both places. In 2017, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported that 2.1 million Americans, about 0.5 percent of the population, suffered from an opioid use disorder*, with overdose deaths in Appalachia almost double the national rate.

In the same year, almost 1.9 million Iranians, a whopping 2.3 percent of the population, abused opium, and that figure doesn’t include heroin and prescription painkiller abuse. According to some experts, Iran is the most drug-addicted country in the world, and the problem only seems to be getting worse.

“In the past seven years, the number of addicts has actually doubled,” said Mehrnaz Samimi, an Iranian-American journalist who has covered the Iranian opioid crisis, especially its effects on women.

Although there are important differences, comprehending the rise of opioid abuse in the U.S. and Iran means understanding the complex interplay of supply and demand for illicit drugs. Since the 1990s in the U.S., supply has come from a combination of pharmaceutical companies and unscrupulous doctors pushing large amounts of highly addictive painkillers, more sincere doctors attempting to better address patient pain, and, in more recent years, illicit supplies of heroin and fentanyl. Demand, in turn, has been driven by a complex mix of increased pain in an aging population and the social and economic dislocation associated with deindustrialization and rising income inequality.

In Iran, most of the supply has come from just one place: Afghanistan. Since at least the 1990s, Afghanistan has been one of the world’s leading opium exporters, being the source of 92 percent of the world’s heroin in 2007. Given Iran’s location on the corridor between Afghanistan and markets to the south and west, some 40 percent of Afghanistan’s narcotics enter the country, and 30 percent of this total remains there.

That fact has made powerful drugs incredibly cheap and accessible in Iran, especially in the poorer border provinces which drug smuggling routes pass through. And, despite the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan since 2001, matters haven’t improved much. In 2016, an opium habit ran a dollar a day in a country where an average high school graduate makes about $10 per day.

The drivers of Iranian opioid demand are more complicated. For one thing, opium has been a major recreational drug in Iran for hundreds of years, which may help explain its prevalence. There’s no getting around one fact though: In the same way that closing factories and mines have driven addiction in the Rust Belt, the Iranian opioid crisis can’t be separated from the country’s economic malaise, driven to a significant degree in recent years by U.S. sanctions on Iran.

“With the sanctions and the economy becoming worse everyday…[People] can’t support their families, and there is a sense of despair that feeds into addiction,” Samimi said.

In 2018, Iran’s unemployment rate hovered between 10 percent and 15 percent, with youth unemployment in parts of the country reaching 50 percent to 63 percent. For comparison, the highest the U.S. annual unemployment rate ever got during the Great Recession was 9.9 percent.

Much like in the United States, the enormity of the opioid crisis has forced Iranian society to explore innovative—and often controversial—solutions. The country’s first methadone treatment center, where addicts are given drugs to lessen the effects of withdrawal and block the effects of opioids, opened in 2002, and the treatment has become widespread despite the familiar issue of drug diversion. Iran opened its first needle exchanges in the mid-2000s and is currently experimenting with injection sites where users can use illicit drugs under medical supervision.

Echoing similar debates in the U.S., Iranians have also fiercely debated the appropriate use of naloxone, a drug that can reverse the effects of an active opioid overdose. In December 2018, Iranian actress Mahnaz Afshar sparked a major controversy when she released an Instagram video enjoining fans to keep the drug on hand in case of a nearby overdose. The Iranian government quickly responded, summoning Afshar before the state judiciary and stating naloxone should only be administered in a hospital.

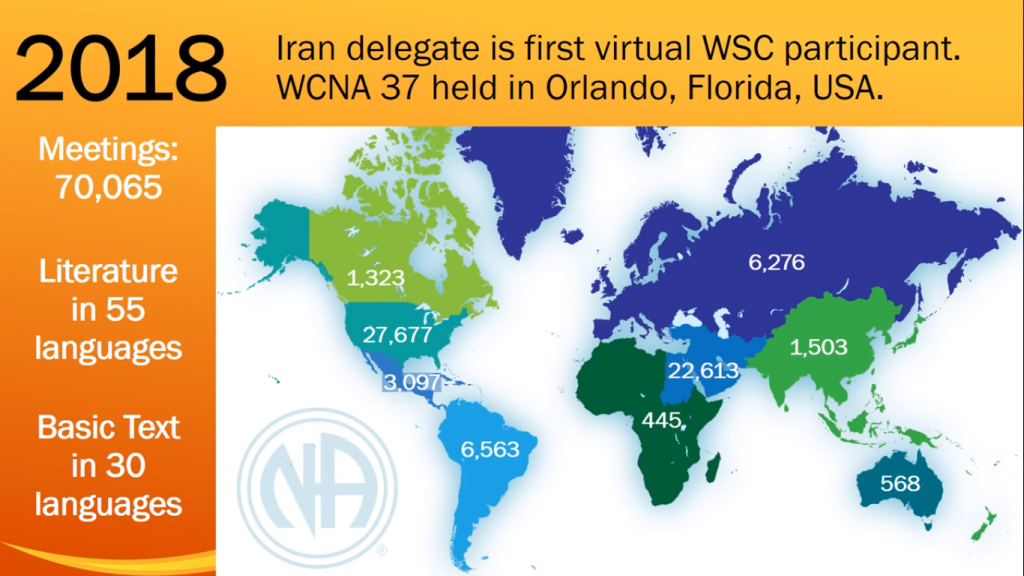

In addition to clinical solutions, recovering addicts have also organized at the grassroots level. Narcotics Anonymous, a peer support network for recovering addicts that is ubiquitous in the United States, has exploded in popularity since its Iranian branch was founded in 1995. Boasting 30,000 members in 2,200 weekly meetings across the country by the mid-2000s, the group reportedly hosted almost 22,000 weekly meetings in 2018.

“Iran is the second largest [Narcotics Anonymous] fellowship of recovering addicts with [the] U.S. being the largest,” said Jane Nickels, a spokeswoman for Narcotics Anonymous World Services.

Despite genuine attempts to grapple with Iran’s drug crisis, significant issues remain. Fifty percent to 70 percent of Iran’s prison population remains incarcerated for drug offenses, and a mandatory death sentence is still in force for several drug-related crimes. Another common solution for authorities is to force drug users into one of the country’s many drug rehabilitation “camps,” which have a reputation for low efficacy and abuse. Furthermore, despite a general push to view addiction as a disease rather than a moral failing, social stigma remains.

“More moderate administrations like the current one…have worked hard to culturalize addiction, and make people understand addiction is an illness,” Samimi said. “They have destigmatized addiction, but not normalized it [as much as in the United States]…It’s kept under wraps a lot.”

Despite these challenges, Samimi thinks Americans should see Iranian addicts and their families as normal people trying to make it one day at a time, just like them. “Most importantly, this is a human problem. It doesn’t matter if you live in Ohio…or Tehran…It’s all the same. It’s all rooted in the same issues,” she said.

As tensions between the U.S. and Iran mount, policymakers would do well to remember this very human—and very familiar—element at stake.

Selected Resources on Drug Use in Iran

- Drug Politics: Managing Disorder in the Islamic Republic of Iran

- “Maintaining disorder: the micropolitics of drug policy in Iran”

- Middle East drugs bazaar: production, prevention, and consumption

- “Out with the old, in with the old: Iran’s revolution, drug policies, and global drug markets”

*2017 DHHS statistics on opioid use disorder do not include synthetic opioids, like fentanyl, which comprise an increasing share of U.S. opioid abuse in recent years.

Nicholas Brumfield is a native of Parkersburg, WV currently working in Arlington, VA. He is also a 2017 graduate of Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service Arab Studies program and a 2015 graduate of Ohio University’s Global Studies program. For more observations about Appalachia and the Middle East, follow him on Twitter: @NickJBrumfield.