Jesse Millan. Via Flickr.

In the 2018 midterms, new and young progressive candidates across the country ran enthusiastic campaigns on change and reform, resulting in election wins. New York, Massachusetts, Minnesota, California, and New Mexico had notable wins for progressives as candidates beat centrist Democrats in their primaries or Republican challengers in general elections.

Some of these candidates are pushing for major reforms on climate change, foreign policy, and education before they are officially in Congress—and are already holding policy talks on climate change, social reform, and economic development. This early action forces both Republicans and Democrats to debate topics that have long been off the table. So, where does Appalachia fit into this progressive wave?

Though Appalachia’s progressives did not win any midterm elections, they remain a force to be reckoned with in the region. Appalachia’s history is filled with vibrant progressive movements demanding labor and civil rights. The absence of electoral success does not mean progressive influence is irrelevant. And some hope for progressive change is on the horizon across Appalachia. This expatalachians series will explore some of the grassroots movements and progressive reformers in the region.

A Short History of Progressivism in the United States

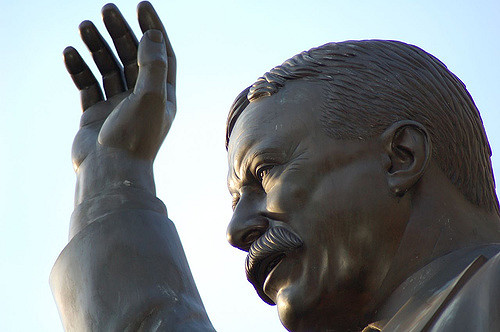

Progressivism is an American reform movement that began during the late 19th century. According to the Center for American Progress, the movement has concentrated “its moral energy against societal injustice, corruption, and inequality.” Many link the on-and-off rise of progressivism to the waves of social movements for civil rights, women’s suffrage, child labor laws, and other human rights issues. Its influence spans class, race, gender, and sexuality. From Upton Sinclair, author of The Jungle, to Martin Luther King Jr., progressive social reformers have affected the lives of Americans.

Progressivism as an ideology has a focus on improving the “public interest” and “public good” via government intervention or legal changes. It is often a community-based approach that focuses on increasing the quality of life for all members of society. A progressive candidate generally wants to reform the political or economic system—or change it altogether.

While some politicians, Republican or Democrat, want the betterment of their communities, their policies are often not oriented toward a “progressive” vision of common good. Instead, progressives see the Republican and Democratic conception of the greater good as ideologically confined by individuals or corporate interests. Furthermore, progressivism is not monopolized by any American political party. By the turn of the 20th century, President Teddy Roosevelt and Wisconsin Governor Robert La Follette were major leaders of the progressive movement— and Republicans. In that time, the progressive wing of the Republican Party set out to break up monopolies and craft labor laws. By the mid-1950s, the progressive movement became affiliated with the Democratic Party through the New Deal, the War on Poverty, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

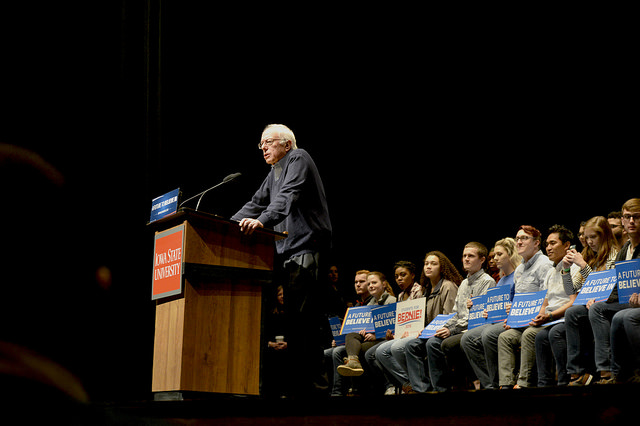

The past few years have brought progressive issues to the forefront. A recent Brookings Institute report estimated that 81 non-incumbent progressives, all Democrats, won races in the 2018 midterms compared to 31 in 2016. During the 2016 Democratic primaries, Senator Bernie Sanders, a long-standing progressive, ran against Hillary Clinton. This race was seen as a battle between two wings of the Democratic party: the establishment, or moderate, wing versus the progressive wing. After Clinton’s loss, Democrats have dealt with intra-party division as progressives ran against establishment Democrats and Republicans alike.

Same Old, Same Old in Appalachian Midterm Results

In Appalachia, few progressives ran for office in 2018 and much of the region voted for its conservative incumbents. In the Georgia governor’s race, Stacey Abrams lost to Republican candidate Brian Kemp, leaving many Democrats and progressives heartbroken by the closeness of the race. 100 Days in Appalachia published the midterm results of Appalachian localities showing that overall, progressives didn’t gain any ground in Appalachia. There has yet to be significant research on what went wrong for progressives in Appalachia, answering why Appalachia hasn’t been a fertile ground for progressives recently.

Some researchers point to the region’s conservatism linked with Bible Belt voters. Others see brain drain, often termed the “struggle to stay,” to explain why many young people with high education levels or LGBTQ citizens choose to leave the region for the cities, either for better jobs or more accepting communities.

However, the people who do stay and fight for a more inclusive vision of home are already changing things. Some youth are organizing in new and exciting ways like Southerners on New Ground, an Atlanta-based group who take action for inclusivity for everyone in Appalachia. Other progressive energy comes from long-standing institutions like the Highlander Research and Education Center, which has been a leader in civil rights since the early 20th century.

Spotlight on the Mountain State

Based on the midterm results, West Virginians didn’t want much change in their politicians. Senator Joe Manchin, the state’s top Democrat and conservative Congressional wildcard, kept his seat. He easily won the Democratic primary against Paula Jean Swearengin and defeated WV Attorney General Patrick Morrissey in the general election.

In West Virginia’s 1st District, the Democratic primary pitted an outspoken and progressive Kendra Fershee against Ralph Baxter, a moderate Wheeling businessman. Though Fershee defeated Baxter, she was defeated heavily by McKinley in the midterms. In the southern part of the state, Democratic State Senator Richard Ojeda lost big to Republican Carol Miller for the 3rd District’s Congressional seat—but he plans to run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020. There were some exceptions, of course, but the U.S. House and Senate elections were clear victories for moderate-conservative candidates.

West Virginia is a conservative-led state—even with a Democratic leader. However, progressives scored some local victories.

In Charleston, for the first time in the city’s history, voters put a Democratic woman in the mayor’s office. Amy Goodwin, a former journalist and communications director, wants to create positive change in the city. She plans to make Charleston thrive by encouraging local business investment and making the city attractive for other kinds of investment. The I Reckon podcast explains her entrance into West Virginia politics and the mayoral election.

Prospects of Future Candidates

And Goodwin isn’t the only West Virginia progressive in the headlines. Last month, progressive organizer Stephen Smith announced his bid for governor with the slogan “West Virginia Can’t Wait.” Smith stepped down as director of the WV Healthy Kids and Families Coalition to run. His motivation statement says:

You can feel it. This is a moment. Every fifty years or so in West Virginia history, the system becomes so broken and our pain becomes so deep that real change becomes necessary and possible. The Civil War, the Mine Wars, the Teachers’ Strike—it is in our blood to fight for our people, no matter their race, their accent, or who their father was.

His statement is reminiscent of progressive labor movements in West Virginia. While his platform is not yet specified, many people expect a progressive and social-reform based candidacy. Even after a Democratic primary battle and a long-shot campaign against incumbent Republican Jim Justice, Smith would still face an uphill battle with a limited state budget and a staunchly conservative statehouse. Time can only tell if this progressive can turn his goals into policy.

Nationally, the “Justice Democrats” and young progressives like New York’s Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez are pushing the Democrats to take more progressive stances. In West Virginia, the most progressive wing of the Democratic Party is the West Virginia Young Democrats (WVYD). In its mission statement, the WVYD notes that its “programs seek to build the youth-base for West Virginia Democratic politics, provide hands-on and intensive training of the under 36 generation and secure a progressive agenda for many years to come.” The group has 23 state chapters.

Progressive Movements in Appalachia

If we look only to elections, we will miss an important trend in West Virginia and greater Appalachia: the existence of fierce and dedicated progressive movements. Although small in number, these groups bring important social justice issues to the forefront of communities across the state.

Since 2016, there has a been a boost in Appalachian social movements’ demonstrations. Recent events have prompted some activists to run for office, but many more are becoming active in local groups. For example, West Virginia is home to strong environmental and labor movements, but it has ripples of LGBTQ and racial justice groups, too.

Indivisible is a national group led by progressive activists whose main goal is to protest and make government action doable for everyone. In fact, many link this group as a major resistance network to Trump’s administration. In Parkersburg, Wood County Indivisible was jump-started as a resistance to some of President Donald Trump’s extreme policies. This group and its other WV county counterparts have pushed government officials to explain and defend policies in a more confrontational way. They advocated for town halls where representatives took questions and explained stances.

More recently, the national group has decided to reorient itself as a progressive group on the offensive. They introduced their offensive guide last month, which could serve as a blueprint for Appalachian organizers. Last week, I spoke with Jeanne Peters, Wood County Indivisible leader, and asked her what she thought about the new direction. “I am very excited that the national Indivisible team has crafted Indivisible 2.0 as a means of leveraging the power that we have now that the Congress is majority Democrat. I look forward to having Wood County Indivisible work closely with the new plan to build more power at the local, state and national level,” she said.

But sometimes, the most organized protests don’t come from progressive activists at all. Red bandanas, a relic of the WV Mine Wars, re-emerged this year during the Teachers’ Strike in West Virginia. Teachers statewide protested their slashing of health care in a state where their salaries and benefits are ranked 45th nationwide. The 55 United Movement not only brought “liberals” to the streets, but an array of teachers of all backgrounds, politics, and ranking. In a Belt Mag excerpt from the 55 Strong: Inside the West Virginia’s Teacher’s Strike, WV teacher Emily Corner noted, “The solidarity that made this strike possible was not built along party lines; we were united around a set of shared grievances and people came together with little concern for party affiliation.” Her analysis emphasizes the loss of faith of average West Virginians in either party.

Even after the strikes ended, West Virginia teachers had the slogan “We will remember in November” in regard to voting for state representatives. One example happened early on in the Republican primary: a more moderate Republican Bill Hamilton beat out the incumbent Robert Karnes, who was adamantly against the Teacher Strike and pay raises. This issue of supporting teachers and education is sure to be on the minds of West Virginians in future elections as well.

Progressive Change in Appalachia

Appalachia is not a stagnant political region. It has a history of flux and clashes as locals fight for progressive values and basic human rights. From the Mine Wars to the New Deal, organizing has adapted to the changing issues in the region. Understanding the politics and people of Appalachia requires looking beyond their elected officials and to the grassroots movements that hold communities together.

Are you a progressive in Appalachia? Are you involved in a community group to bring change to your area? I want to talk to you! If you want to be part of the discussion, please email me at alena@expatalachians.com

Alena Klimas is a writer and cofounder of expatalachians. Klimas is passionate about community and economic development in West Virginia. In Parkersburg, WV, where she grew up, she’s been a part of grassroots movements for LGBTQ inclusivity and reform. To learn more about the expatalachians team click here.