Throughout March, national parks and forests across the United States shut down. In April, many more will due to the coronavirus. Quarantine rules still allow Americans to get outside, unlike people in Italy or Spain. However, parks have closed so staff aren’t put at risk—as well as to protect mountain rescue volunteers. The failure of the public to follow social distancing recommendations and less-experienced hikers flocking to national parks has led to a spike in emergency rescue calls, putting rescue workers at risk of catching the coronavirus.

As the coronavirus spread in urban cities on the east coast, many people sought the outdoors of Appalachia for social distance. Some are looking for short-term rentals to ride out the pandemic. For a while, Washington, DC residents were encouraged to visit West Virginia because there were “no cases” in the state—though Maryland’s DC suburbs already had a rising number of cases. In Buncombe County, North Carolina, direct flights to New York, Washington DC, and more made Asheville easily accessible to tourists.

The increase in foot traffic cannot only be blamed on outsiders, though. As major layoffs take effect, many Appalachians are escaping to the trails and parks to cope.

As park visitors increase, so do calls to mountain rescue volunteers (Or SAR, search and rescue). The Mountain Rescue Association asked visitors to cut back on their hikes due to “an increased number of search and rescue callouts.” Trail runners should not take a 28-mile workout alone. New hikers shouldn’t go into the woods for a 12-mile hike without a map. SAR volunteers are ill-prepared to help during these times.

“Every time a SAR team gets deployed, the members of that team voluntarily put themselves in harm’s way for the sole purpose of helping someone in need,” Ari Forteni, president of SAR, wrote. “With the COVID-19 virus continuing to spread, every time a team gets called out, we now face an additional threat above and beyond the usual hazards.”

In Appalachia, many popular parks are closing trails and campsites to limit the strain on rescue volunteers and prevent congested trails. Dupont State Forest, with its popular waterfalls, closed on March 23. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park shut down on March 24. And the North Carolina Arboretum, just outside Asheville, also shut down on March 30.

So far, seven employees of the U.S. Park Service have tested positive for the coronavirus, though the Park Service did not say where every employee worked. A Great Smoky National Park employee tested positive for the coronavirus last week—one day after the park closed.

Many national parks, though remain open. That is largely because the Trump Administration’s Department of the Interior has yet to close the Park Service nationwide; more than 300 parks are open. Many national symbols have already closed, such as Arches National Monument, Yellowstone, and the Statue of Liberty. The decision to close parks isn’t always so cut-and-dry, however.

For many parks and recreation areas, visitors will come regardless of whether it is officially closed. The Park Service can only do so much with current staffing and resource levels. The Appalachian Trail, for example, is nearly impossible to close a trail that runs the length of the United States. “The Appalachian Trail, given its ever-increasing popularity over the past weeks, is no longer a viable space to practice social distancing,” the Appalachian Trail Conservancy noted, and closed its trailheads. Many thru-hikers who planned to do the trail are postponing or canceling their trips because they feel a moral responsibility to protect public health.

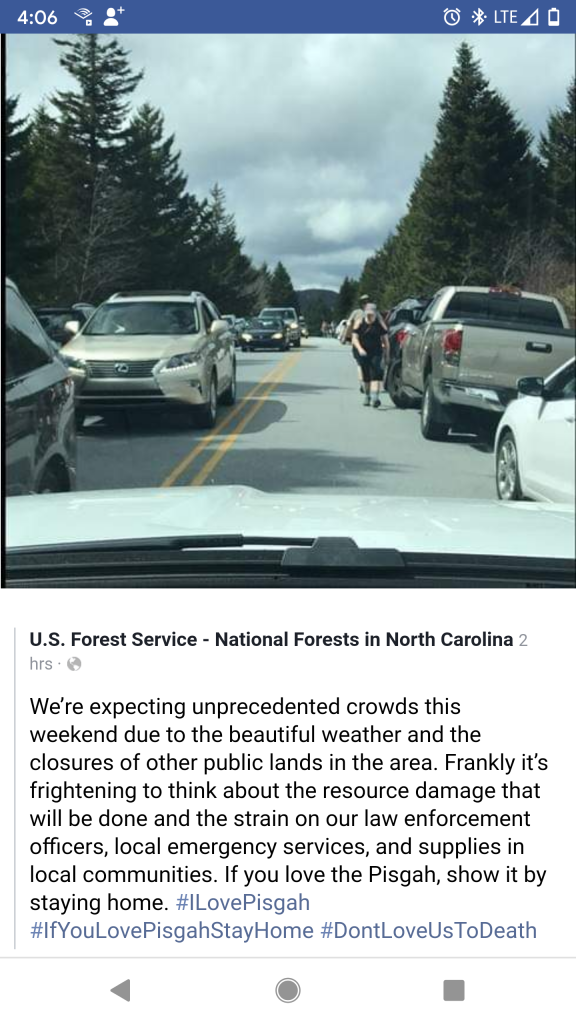

The Appalachian Trail Park Service staff, much like Pisgah National Forest in North Carolina, has very little control over stopping all access to the trail. They can block roads and access points, but determined hikers can still reach it. Closing the park completely could mean fewer staff members on site to assist injured hikers. Therefore, some parks are minimizing access while staying open.

Shutting down parks could also hurt outdoors-focused local economies. Park closures will have devastating effects on communities such as Fayetteville, West Virginia; Asheville, North Carolina; and Gatlinburg, Tennessee, which rely on tourism. Gatlinburg, in Sevier County, for example, is a major entrance into the Great Smoky Mountains and has Dollywood theme park. In 2019, the county had 11 million visitors. This year, those numbers will plummet, having a devastating effect on restaurants, guiding companies, and local tax revenues.

While leaving affected areas for solace and green space might sound responsible, it ignores the possibility of community spread. In Appalachia, where the health infrastructure isn’t always as strong as in urban areas, the impulse to get into the woods could have drastic consequences. Tourism-reliant areas will need to weather an economic decline in the coming months; if people practice social distancing, they need not weather a health decline as well.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Alena Klimas is a writer and cofounder of expatalachians. She also manages the weekly newsletter, The Patch. Klimas recently moved to Asheville, NC to work on regional development projects with a small consulting firm. She enjoys the vibrant outdoors and beer culture in her new home.