This past November, something groundbreaking happened in eastern Kentucky. At the Pine Mountain Settlement School in Harlan County, dozens of young Black people from across Central Appalachia gathered at the first Black Appalachian Young and Rising (BAYR) meeting.

To the uninitiated, the meeting’s goal was simple: Create a space where young Black people in the region could come together, talk about their issues, and celebrate their shared existence. However, to anyone familiar with Appalachia’s long history of marginalizing its Black population, the gathering’s affirmation of Black existence and joy was nothing short of revolutionary.

“We all knew this was bigger than any of us,” said Mekyah Davis, BAYR’s coordinator, about the project.

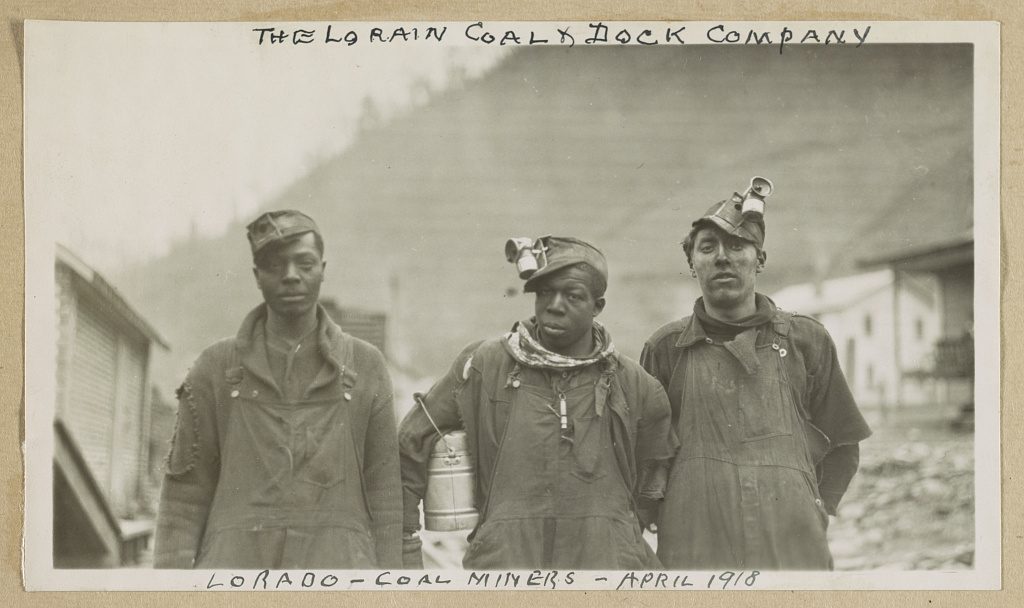

As many scholars have attested, Black people have a long history in Appalachia, with evidence suggesting that Africans escaping Spanish enslavement were among the region’s first non-indigenous inhabitants. Prior to the Civil War, enslaved Blacks were forced to work in Appalachia’s most iconic—and dangerous—industries, and Black miners played a significant role in the region’s coal and labor history in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Notwithstanding that important presence, white supremacist power structures have consistently sought to erase Black Appalachian existence from the region— literally and figuratively. When they could not control Blacks through slavery, Appalachian states passed laws restricting free Black residency. When the regional coal economy came undone in the mid-20th century, Black miners and their communities were the first to lose their jobs and face economic hardship. Even today, state educational curricula whitewash the region’s deep history with slavery, and the idea of Appalachia as a “white” area remains dominant despite Black communities’ continued existence.

Although many Appalachian scholars and activists have struggled to fight this erasure, institutional racism remains a difficult barrier. For Davis, a native of Big Stone Gap, Virginia who now lives in east Tennessee, the idea for Black Appalachia Young and Rising came after he joined other regional organizations, like STAY and the Appalachian Studies Association, and felt they lacked Black perspective.

“I realized the spaces I occupied were very white-centric. There wasn’t a lot of space for young Black leaders,” Davis said.

To change that, Davis and others in the Black Appalachian Young and Rising steering committee, with help from the STAY Project, organized a space controlled by Black Appalachian youth, for Black Appalachian youth.

“The most important goal was to address the critical need for Black youth leadership and representation in our region…We want to overcome the physical and psychological isolation we too often face, continue to examine and build a collective Black Appalachian identity, and celebrate the joy of being together,” he said.

In pursuing this mission, BAYR has drawn on an extensive network of Appalachian organizations and personalities with a history of centering Black experiences. Representatives from the Appalachian African American Cultural Center and Affrilachian Memory Plays attended the Pine Mountain meeting in November, and Davis pointed to Charice Starr, a Popular Educator with the Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee, as an especially important influence for the project.

“Charice is a dear friend, a mentor. She has been an infinite source of support and wisdom in grounding me not just in the history of the region, but in Black movements throughout the Global South,” Davis said.

Davis also cited Dr. William Turner, a pioneering scholar of Black Appalachian history at Berea College in Kentucky. “Dr. Turner kind of took me under his wing and just tried to give me some of the history of Black folk in the region. He gave me a sense of urgency in terms of doing [the project] now… This was the time,” Davis said.

BAYR’s first gathering started a conversation about the challenges and needs of being young and Black in Appalachia. Some of the challenges, like the opioid epidemic, will be familiar to white locals as well. However, in addition to dealing with the same structural issues faced by most Appalachians, BAYR highlights how young Black people face unique barriers rooted in racism, state violence, and economic injustice, including the “homogenous white narrative of the region.”

“I think some of the challenges are a lack of resources in terms of visual presentation of dignified Black leadership. A general lack of investment in youth centers. Organizations are using diversity and equity as buzzwords. [But] they’re not really investing in and bringing in diverse opinions and voices.” Davis said.

In spite of these challenges, the first BAYR gathering identified several steps forward, with Davis underlining his desire to strengthen relationships with other groups working with Black folk in the region, like the educational initiative Black in Appalachia, and plans to make BAYR a permanent program of the STAY Project. However, the most important thing the meeting determined was the need to continue BAYR’s core goal of providing a space where young Black people are free to be themselves together.

“Most important was the realization of how crucial and necessary it is for young Black people to come together by themselves…to create Black autonomous space,” Davis said, “We’re having the chance for young Black folks to be engaged in spaces they might otherwise not have access to…For young people to step into their collective knowledge and power.”

As BAYR enters a new phase and seeks to expand its networks and resources, keeping that mission at its heart will be key to ensuring its continued success.

“Right now, we have the opportunity to find out how to get people to invest in us…We acknowledge the historical trauma and oppression black folks have faced in our region. Despite that, we are creative, ingenuitive, determined young people. We are out here creating space for ourselves and paving our own futures for the world we envision, but we still need some support.”

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nicholas Brumfield is a native of Parkersburg, WV currently working in Arlington, VA. He is also a proud sustaining member of WOUB Public Media. For more hot takes on Appalachia and Ohio politics, follow him on Twitter: @NickJBrumfield.