For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, Appalachia was built and sustained by the railroads that blasted, tunneled, and twisted through its mountainous terrain. These routes ferried people who settled previously desolate locales as the trains hauled coal, iron, and steel to fuel the region’s economy.

The dominance of railroads began to decline, however, as highway improvements allowed for cars and trucks to reach even the most remote mountain towns. By the time passenger rail service was nationalized in 1971, private railroads such as the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) had phased out and abandoned many of their passenger routes as road and air travel increased.

After rail became less valuable, though, its abandoned routes have found a new use in recent years.

While the tracks on most defunct lines were removed for scrap, many tunnels and bridges remain intact, as well as the gravel roadbeds and legal rights-of-way.

The remnants of railroads give some Appalachian towns a chance to strengthen regional connections and draw in some tourists by creating recreation trails for non-motorized vehicles along abandoned railroads.

Though railway freight service held out longer, de-industrialization along the Ohio River Valley and coal mine closures drove rail passenger numbers to a breaking point by the 1980s. By the 1990s, many branch lines and arterial routes were abandoned. These closures included two storied mainlines: The B&O’s St. Louis Mainline between Parkersburg and Clarksburg in West Virginia and Western Maryland Railway’s Mainline between Cumberland, Maryland and Connellsville, Pennsylvania.

The towns along those routes faced virtual annihilation. Many were “railroad towns” whose entire purpose was to serve the trains, crews, and passengers that rumbled through. Today, the importance of Appalachia’s rail network can be seen in towns such as Matewan or Thurmond in West Virginia where the original entrances of commercial buildings face the tracks rather than the street.

Inspired by the success of adaptive reuse of abandoned railroads into recreation trails in the Midwest, some groups have explored similar efforts in Appalachia. Among the first trail conversion was a nine-mile segment along the former Western Maryland line running southeast from Ohiopyle, PA, which opened in 1986. Already the site of a state park, the trail’s scenic location along the Youghiogheny River and proximity to a popular recreation spot drew thousands of visitors in the early years, serving as a template for rail-to-trail projects in the region.

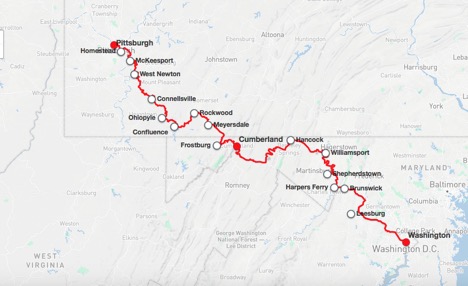

From the initial nine-mile segment, the Western Maryland route was eventually extended from Pittsburgh, PA to Cumberland, MD as the Great Allegheny Passage Trail (GAP).

The GAP trail connects with the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Towpath in Cumberland, then continues to Washington, DC. The 150-mile trail between Pittsburgh and Cumberland alone attracts more than 800,000 visitors annually. While the recreation and tourism industry has not replaced the jobs and commerce that came with the railroad, the steady stream of cyclists has brought some tourism dollars into the “trail towns” along the route.

Based on the success of trails such as the GAP, the number of rail-to-trail projects has risen since the 1980s. Some are longer, such as the North Bend Rail Trail that follows the former B&O St. Louis Mainline in West Virginia, while others run for only a few miles, such as the Tweetsie Trail in Johnson City, Tennessee. The trails with the biggest economic effect are the longer multi-day trails that require visitors to use services such as hotels, restaurants, and bicycle repair shops.

To spur more economic activity, some groups want to connect smaller trails and build trail systems stretching hundreds of miles long.

One of the most prominent proposed trails in the region is the Parkersburg to Pittsburgh (P2P) network which, when completed, will join the existing GAP trail near Connellsville, PA and connect northern West Virginia to southwestern Pennsylvania and Washington, DC. By closing 52 miles of gap segments, the P2P network will bring together six existing trails and stretch more than 175 miles. More than 16 cities, counties, and regional governmental organizations have signed on to the project.

Appalachia is undeniably a region inundated with economic upheaval. While bedrock industries such as manufacturing, railroads, and resource extraction will not employ as many people or pay as many taxes as in the past, innovative and adaptive reuse of the physical infrastructure left behind can help some small businesses stay afloat and encourage new ones to open.

That effect can already be seen in existing trail towns: With a population of under 300, the town of Cairo, WV along the North Bend Rail Trail may arguably be one of the smallest towns in America with a bike shop.

Ready to ride? Find out a rail trail near you here.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.

Nick Musgrave first became fascinated with West Virginia’s history while growing up in Parkersburg. He continues to read, research and write on the Mountain State’s past from its birthplace in Wheeling. For more neat history and some political snark, follow him on Twitter: @NickMusgraveWV.