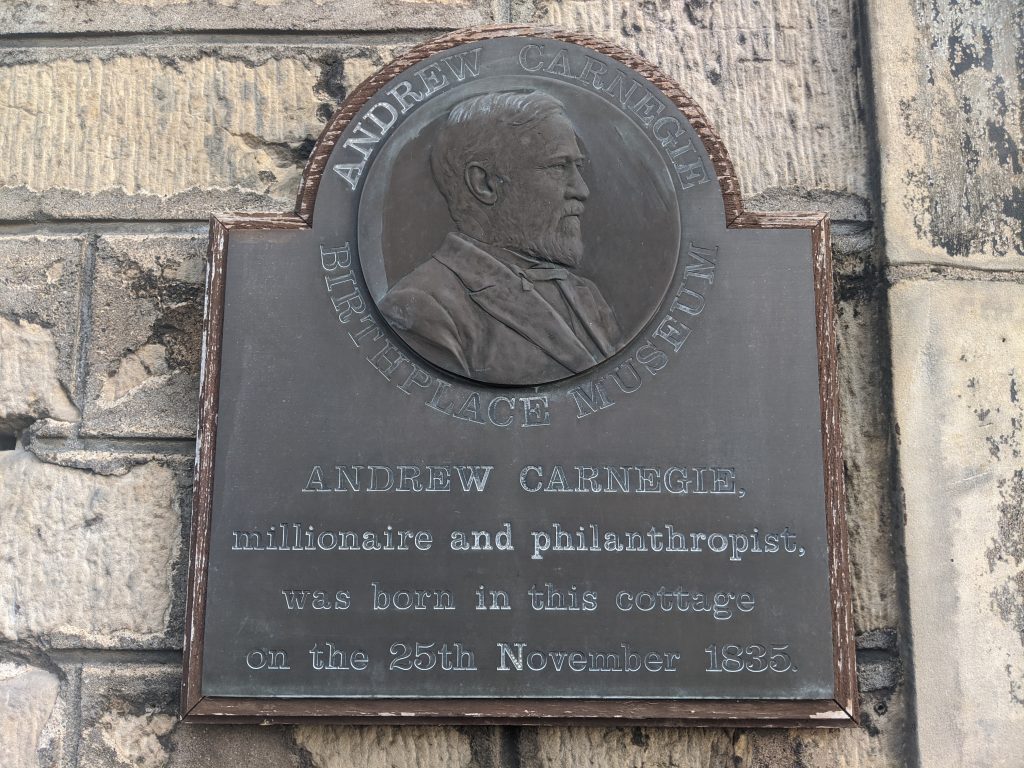

My recent move to Edinburgh, Scotland has me finding connections to my hometown of Pittsburgh everywhere. One big connection is Andrew Carnegie, the steel industrialist, who was born in Scotland. His birthplace, Dunfermline, is just across the water from Edinburgh in the county of Fife, (or the Kingdom of Fife as locals call it).

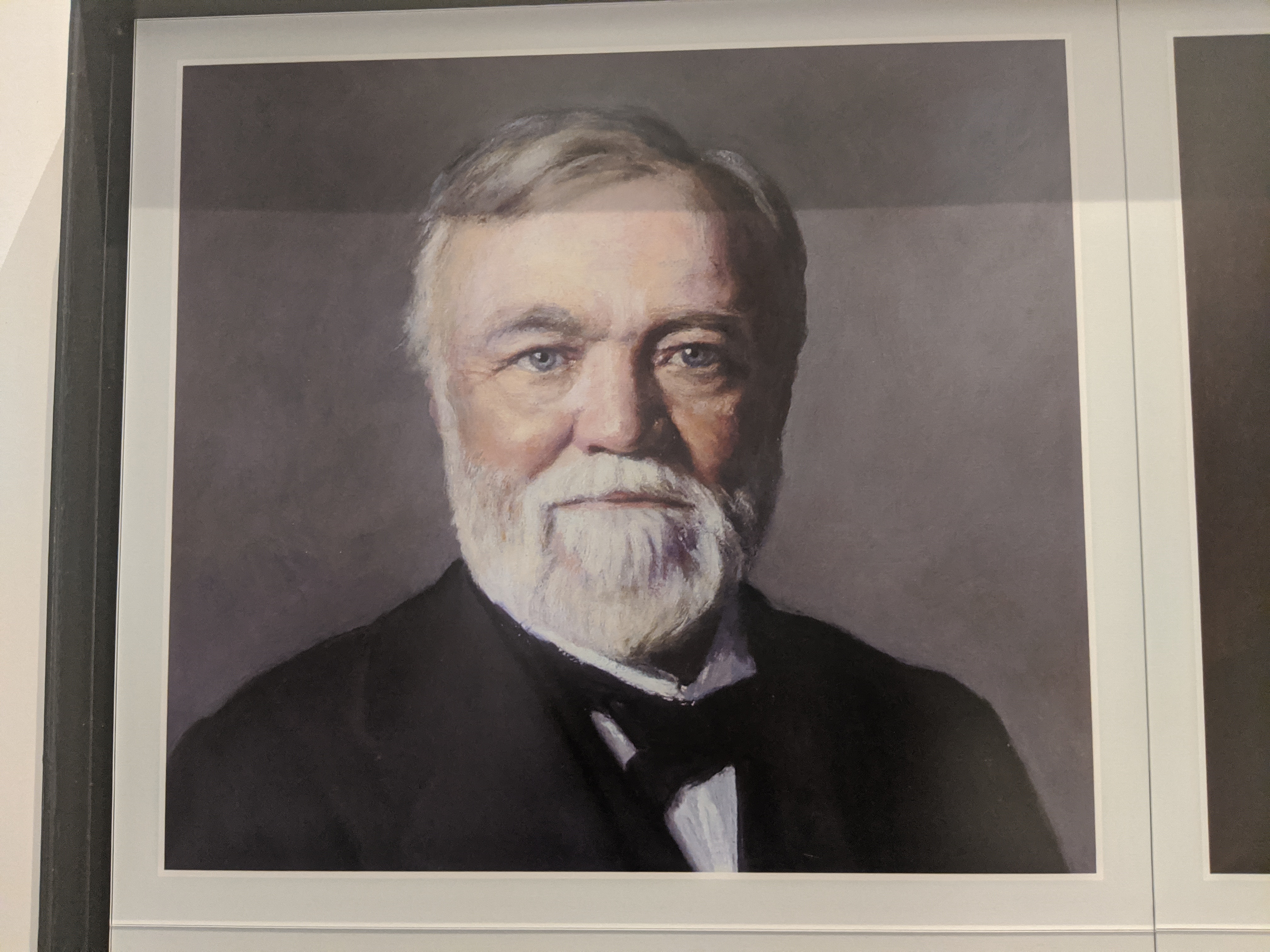

The town has an Andrew Carnegie Birthplace Museum and Carnegie Library and Galleries, which compelled me to visit. So, I hopped on the X52 bus from Edinburgh and off I went.

I arrived at the Dunfermline bus station and walked down a path into town. There, I found signs that guided me to the museum. Unfortunately, the museum was closed for renovations, but I walked the perimeter of it which consists of the cottage where Carnegie entered the world and a small addition that contains the museum. I continued on to Pittencrieff Park, opposite the museum. The 76-acre park was a gift from Carnegie to the city in 1902. The highest point of the park has a statue of Carnegie overlooking the land.

I must admit that the park is beautiful. A stream runs beside a well-maintained walking path. Moss-covered bridges, lush foliage, and playgrounds create a family-friendly park that looks like something from the pages of The Secret Garden. Even on a gloomy weekday, there were a number of visitors.

The whole town clearly benefits from their connection to Carnegie. In addition to the park and museum, there is a Carnegie Drive, Leisure Center, Hall, Primary School, Conference Center, and Library. There is also Pittsburgh Street, commemorating the city where he made his fortune.

Besides my move across the pond, another impetus behind my visit was an article I wrote last year about Carnegie’s legacy. After publishing, I wondered if I had over-glorified Carnegie. When I wrote it, nostalgia for the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh made me feel grateful for his philanthropy in Pittsburgh and elsewhere. After some reflection, my appreciation turned to resentment toward him for being an unabashed capitalist, who valued efficiency over the safety of his workers.

Others have written about the contradictions in Carnegie’s life. He is most famously known for breaking the Homestead Steel Strike of 1892 in which he (alongside Henry Clay Frick and the Pinkerton security force) destroyed a worker’s union. The strike resulted in around a dozen deaths that remain a stain on Carnegie’s legacy. Another gaping contradiction is that Carnegie amassed an astounding fortune, bringing him immense wealth during his life, while many of his workers lived in poverty. This occurred despite his belief in distributing wealth.

Many people, myself included, live in a mess of contradictions. Yet I’m still angry at Carnegie. The capitalism he practiced industrialized and brought wealth to Pittsburgh, but not without large costs. Many lives were tragically lost in the steel mills. “Newspaper lists of men killed and wounded each year were as long as a casualty list for a small battle in the American civil war,” The Economist noted. Beyond the workers, who were subjected to unsafe conditions, citizens faced the threat of unchecked pollution spilling from the mills. This is a legacy that lives on today in Pittsburgh as the city continues to suffer from horrible air quality.

Maybe it’s harsh to blame Carnegie, but he deserves criticism for his failures just as he receives praise for his philanthropy. I should also add that it is puzzling to me that philanthropy is glorified at all. The idea of philanthropy is that the rich, with their accumulation of wealth and power, decide if, how, and when to help the public. Why do the rich get to decide what benefits the public? The failing of philanthropy extends beyond the historical to the contemporary with examples like Jeff Bezos, who funds homeless shelters despite his company, Amazon, fueling the Seattle affordable housing crisis and opposing a local business tax that would have funded affordable housing. Another example is Dick and Betsy Devos. Their foundation has given millions of dollars to organizations with controversial agendas, like opposing abortion and questioning climate change. But I digress.

I do not want to romanticize Carnegie’s legacy, but it was interesting to think about how this person adjusted to Pittsburgh when he first arrived. Pittsburgh in 1848 offered the Carnegie family economic opportunities that industrialization, ironically, had taken away from them back in Scotland (Carnegie’s father was left jobless due to the mechanization of weaving).

Carnegie loved Scotland. He frequently returned home and gave much of his money to the country. I understand—Scotland is truly beautiful. I also understand because I have the same love for Pittsburgh. I still miss it. Pittsburgh may not have the hills and foliage of Scotland, but it does have miles of bike lanes, beautiful public parks, and a distinct culture stemming from the steel industry, topography, and immigration.

Whether I like it or not, I inherited the world after Carnegie and live with his legacy. Walking in his footsteps has allowed me to contextualize my own life and more deeply consider the history of capitalism and injustice that is impossible to escape. My ability to study in Scotland (a huge privilege) connects to so many other things (my race and socioeconomic status, to name a few) beyond Carnegie. However, his legacy and its problems cannot be ignored. His investment in cultural institutions cannot atone for the lives lost in the steel mills or the pollution he bestowed upon Pittsburgh. He put Pittsburghers in danger while he vacationed in the clean air of the Scottish Highlands at his castle. Carnegie only helped Pittsburgh after Pittsburgh helped make him wealthy.

Annie Chester is a writer and co-founder of expatalachians. She writes about the environment and culture in Appalachia and abroad. She is currently a postgraduate student at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.