When one thinks of Appalachia, Canada isn’t the first place that comes to mind. Indeed, the two areas may as well be polar opposites for many Americans, with Appalachia seen as a distinctly southern region and Canada being the geographic definition of northern.

However, this division doesn’t hold up in reality.

Looking at a map of eastern North America, the Appalachian Mountains do not stop at the US-Canadian border. Starting in the southern foothills around Birmingham, Alabama, they stretch northward some 1,500 miles, breezing past the Mason-Dixon line into Pennsylvania and New York, then into the color-coded mountains of New England, before fanning out in the Canadian provinces of Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, meeting their chilly end on the island of Newfoundland.

We aren’t taught to look at Appalachia this way—from Birmingham to New Brunswick—for a variety of reasons. After all, Appalachia isn’t just a geographic region, but an area seen to possess distinct cultural and socioeconomic characteristics that set it apart from other areas of the Appalachian Mountain chain. However, if one can suspend their preconceptions about what is and is not Appalachia, they might be surprised at what a more inclusive view of the region that allows for Appalachian Canada can teach us.

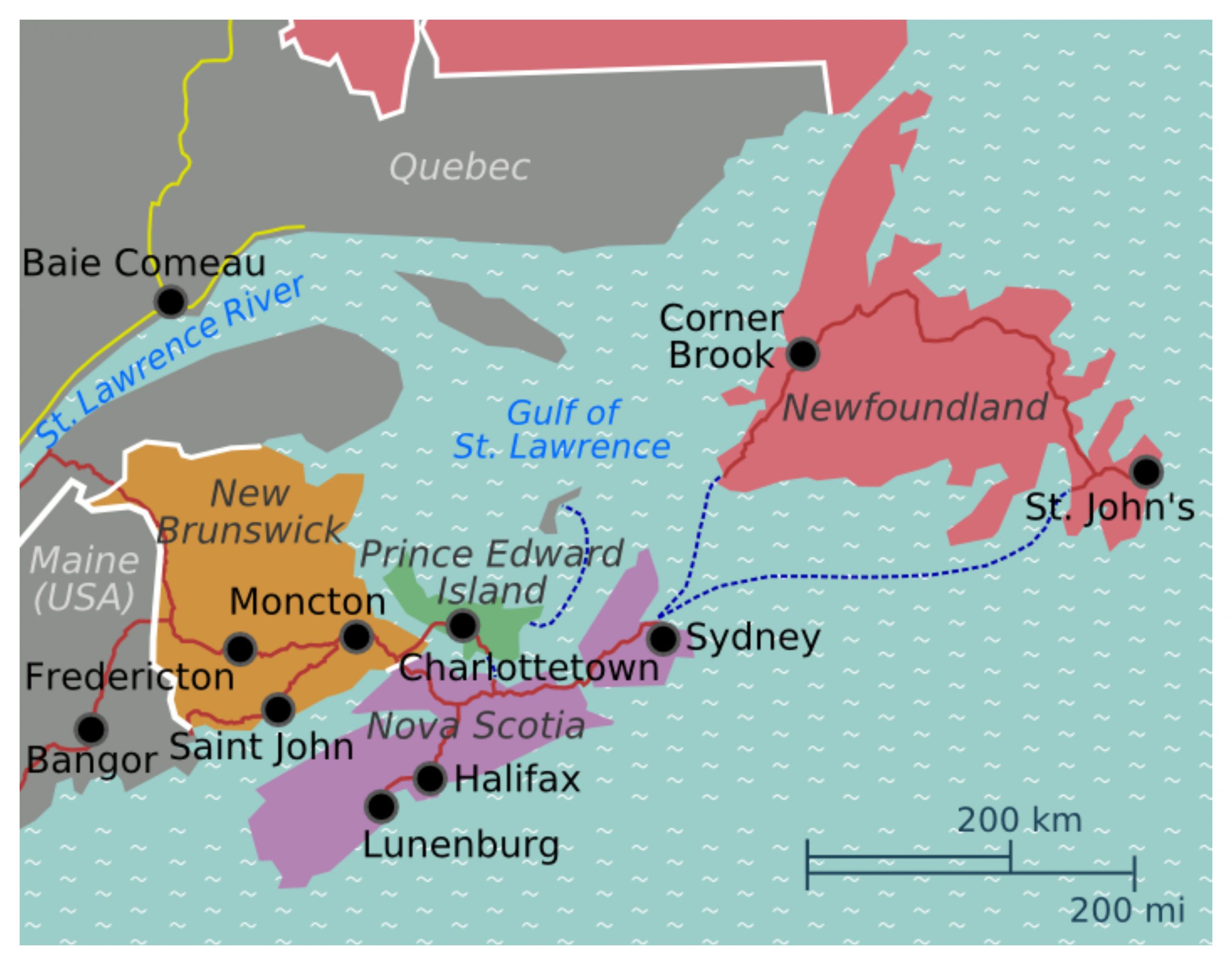

At its largest extent, Appalachian Canada covers much of Canada’s eastern seaboard, including all of the province of New Brunswick and smaller portions of Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Newfoundland, which is separated from the rest by the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Like their American cousins the Great Smoky and Blue Ridge Mountains, much of the Canadian Appalachians are subdivided into smaller ranges, with the Notre Dame and Chic-Choc Mountains in New Brunswick and Quebec, and the Long Range and Annieopsquotch Mountains in Newfoundland.

Although not synonymous, much of Appalachian Canada overlaps with the Maritime Provinces, a coastal region of eastern Canada that—like Appalachia—has an economy dependent on exporting natural resources and has been stereotyped as poor and culturally backward.

Aside from geography, this similar social and economic history is perhaps the most compelling reason to include Appalachian Canada, especially the mountainous and heavily forested province of New Brunswick, in discussions about Appalachia. Much like the “southern mountains,” the majority of Appalachian Canada’s population is descended from 18th- and 19th-century settlers from the British Isles, with smaller numbers from eastern, central, and southern European migrants attracted to the region’s resource-based economy.

As in central and southern Appalachia, Appalachian Canada’s dependence on forestry and mining has also produced a distinct local history marked by inequality and labor conflict. Despite containing Canada’s poorest provinces, Appalachian Canada is also home to some of the country’s richest people. In particular, the New Brunswick-based Irving family, Canada’s 8th-richest in 2018, made its fortune through exploiting Appalachian Canada’s natural resources and ruthless vertical integration. In the 1970s, the family was reportedly the single largest landowner in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Maine, echoing coal and steel barons’ similar economic dominance of Appalachian America for much of the 20th and 21st centuries.

While possessing many similarities, Appalachian Canada’s unique history has also set it apart from areas farther south. Perhaps most notable to an American observer is that the area is much more linguistically diverse. Originally colonized by the French, about one-third of New Brunswick’s population is Francophone, and it is the only officially bilingual province in all of Canada. This is in stark contrast to the U.S., where several Appalachian states have explicitly declared English to be their official language, and West Virginia consistently ranks last among states by population that speak a language other than English at home.

Less noticeably, but no less importantly, Appalachian Canada also has a larger Indigenous community compared to Appalachian America. Undoubtedly, the Canadian government has subjected Canada’s Indigenous peoples to many of the same genocidal policies enacted by the U.S. government against Native Americans. However, it did not pursue a policy of Indian removal similar to that pursued by the U.S. in Appalachia, wherein over 100,000 Cherokee, Creek, and other Native Americans were ethnically cleansed from the mountains to make way for white settlers.

This different history is reflected in Indigenous peoples comprising a much larger percentage of Appalachian Canada’s population. While Native Americans often make up less than 1 percent of the population of any Appalachian state—North Carolina, home to the Eastern Band of Cherokee and Lumbee tribes, has the highest percentage with 2 percent—Indigenous peoples make up more than 3 percent of the population in several Appalachian Canada provinces, with Nova Scotia registering an Indigenous population of 6 percent in 2016.

This larger population has given Indigenous peoples in Appalachian Canada greater visibility and bargaining power vis-a-vis Canadian authorities than their American counterparts, who are often ignored in conversations about Appalachia by even the most well-meaning of voices. Indeed, over the past year, members of the Mi’kmaq people indigenous to Nova Scotia and other parts of Appalachian Canada have attracted international attention in their ongoing fight to protect their long-held fishing waters from settler encroachment.

As it stands, there does not appear to be any widespread attempt among Canadians living in the Appalachian Mountains to identify themselves as part of Appalachia. However, in recent years, some Americans have attempted to consider what an expanded definition of the region might mean. In particular, members of the burgeoning “Northern Appalachia” literary movement have begun to ask whether the idea of Appalachia might be able to accommodate our friends to the north. In his 2019 memoir Appalachia North, Matthew Ferrence of Allegheny College considers how drawing on geology, environmental sciences, and other ways of understanding Appalachia can subvert the restrictive narratives we’ve been given about the region to include “Canappalachia.”

Only time will tell whether Appalachian Canada will catch on. In the meantime, tentatively expanding our ideas about what Appalachia is can help us better understand the region and its issues. In its similarities, “Canappalachia” can help Appalachian Americans better understand how regional issues are part of much larger global problems—an understanding that can help build solidarity with other regions like the Maritimes. Conversely, in its differences, Appalachian Canada teaches us the specificities of the issues we face and highlights aspects of ourselves we’d forgotten.

Nicholas Brumfield is a native of Parkersburg, WV currently working in Arlington, VA. For more hot takes on Appalachia and Ohio politics, follow him on Twitter: @NickJBrumfield.

Subscribe to The Patch, our newsletter, to stay up-to-date with new expatalachians articles and news from around Appalachia.